Clothing, influenced by fashion trends, has been fickle in many cultures, liberally undergoing changes over time. This is more so today than ever before. Fashion changes—although admittedly not as frenzied as today—also took place in the olden days, so much so that one can easily discern the era a painting or a photograph belongs to by simply studying the attire of its wearers.

However, it isn’t easy to apply this rule of thumb to Sri Lanka. Not only did the colonial influences we were subjected to outlast the actual rule of our Portuguese, Dutch and British rulers, but they also spilled over to the reigns of other colonial powers, making our sartorial landscape a complicated one. Although we are prone to thinking that the Western attire we commonly wear today was introduced to us by our British rulers, they were actually introduced a couple of centuries earlier, when the Portuguese ruled our shores.

So let’s see who introduced what, keeping in mind that they all contributed to the making of a colorful tapestry of clothing that we can be proud of as Sri Lankans.

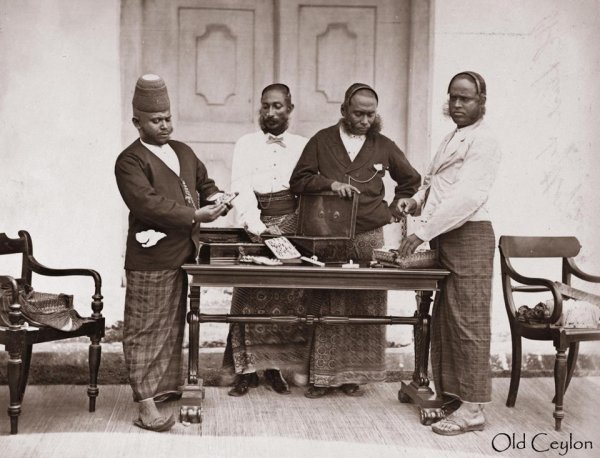

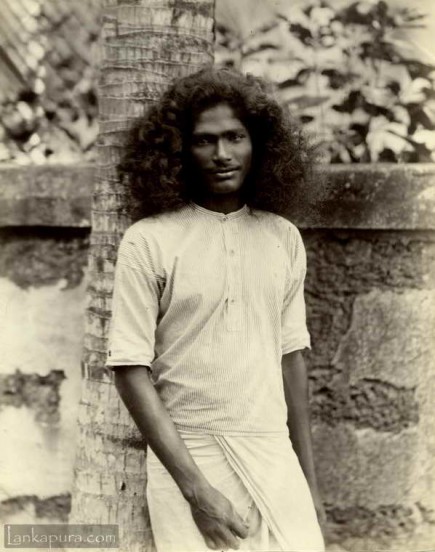

Shirt

lankapura.com

The shirt as we know it today was not introduced to us by the British, as is popularly believed, but by the Lusitanian rulers of our coastal areas. Kamisa, the Sinhala word for shirt, comes from the Portuguese camisa.

The Portuguese, in turn, seem to have received it from the Roman conquerors of old or borrowed it from the Arabs. The earliest mention of it comes from St. Jerome, an Italian priest who mentions camisa of linen worn by soldiers in his Epistle to Fabiola (C.395), though we are not sure what the word actually referred to. In fact, there are those like Father Joao De Sousa, the compiler of a renowned work on Arabic loans in the Portuguese language, Vestigios Da Lingua Arabica Em Portugal (1789) who trace it to the Arabic qamis or tunic. There is some evidence to support this view. For instance, we have Duarte Barbosa who says in his Viage Por Malabar y Costas de Africa (1512) that the Moors of Ormuz “go about in very fine long white cotton camisas of very fine texture”.

Be that as it may, it was the Portuguese who popularized the shirt and made it an article of everyday wear. On his epic first voyage to India, Vasco Da Gama took along plenty of shirts, which he generously gave away in the shores where he sojourned. Lopes De Castenheda in his Historia (C.mid-16th century) observed that the famous navigator liberally parted with camisas to win the favor of those he found useful for his colonial exploits. He recorded of one such instance: “Vasco de Gama received him very kindly and ordered camisas to be given to him”.

Trousers

Trousers were probably introduced to us by the Arabs but did not gain wide currency till the Portuguese entered the scene. These were rather loose trousers known as saruvaala (from the Arabic sirwal), somewhat resembling short trousers. They were worn by Sinhalese peasants in certain areas, especially when working in the fields, till about the early part of the twentieth century.

However, trousers were not widely worn here till the Lusitanians arrived on our shores. It was at this time that they slowly but surely found their way even to the royal households of the Kandyan Kingdom. Robert Knox in his Historical Relation of Ceylon (1681), describes the reigning king of the time, Rajasinha II, wearing long breeches to his ankles.

Kalisam, the Sinhala word for trousers, in fact, comes from the Portuguese calcao meaning breeches or pantaloons, although in modern Portuguese it could mean shorts or even trunk. More commonly, in modern Portuguese, trousers are known as calcas as in calcas-boca-de-sino (or bell-bottom trousers). In French, the related word calecon means ‘underpants’. The Latin term from which it originated calceus meant ‘shoe’ or ‘half-boot’ hence the expression calceos mutare ‘to become senator’ as the senator wore a peculiar sort of half-boot.

Socks

pxhere.com

The Portuguese were also the first to introduce socks to our country, though these were originally more likely to have been stockings. Mes, the Sinhala word for socks, comes from the Portuguese meias, which seems originally to have meant stockings. The word is seen in old Portuguese lexical entries like meias de la or woolen stockings and meias de seda or silk stockings (A New Dictionary of the Portuguese and English Languages. Jose Maria De Lacerda, 1871)

Shoes

pinterest.com

Although hard to believe, shoes were unknown to Sri Lankans before the Portuguese set foot on our shores. The footwear that our Lusitanian conquerors wore were called sapato. The Sinhala sapattu in fact comes from this Portuguese word sapato, which originally meant a clog or wooden shoe.

Prior to the conquista, people mostly went about barefoot or at most wore slippers or sandals. As the English traveler Robert Knox observed of the Kandyan Kingdom in his monumental work, Historical Relation of Ceylon (1681), “Neither men nor women wear shoes or stockings, that being a royal dress, and only for the King himself”. We also have Christopher Schweitzer in his Journal of Six Years’ East Indian Journey (1682) telling us that the Sinhalese King’s shoes were only leathern soles with straps set with sapphires and rubies. He added that the King’s Corals or governors of counties wore a sort of slipper made of wood in such a manner that they hung only on a wooden peg between the great toe and the next.

However what the Portuguese introduced here back in the 16th century were probably not the leathern shoes we are used to today, but wooden clogs such as those worn by French and Dutch peasants and working class people up to the early part of the 20th century. These clogs were handmade of hardy wood such as beech. Interestingly, sabot, the French word for these clogs (related to the Portuguese sapato and our sapattu), is the origin of the word saboteur which means ‘to make a loud clattering noise with sabots’. This, in turn, gave rise to the English word sabotage. Legend has it that French workers disrupted new machines they considered threats to their livelihood by chucking their sabots into machines (Wood, Craft, Culture, History. Harvey Green.2007). And so we have the word sabotage!

The Portuguese term for shoe also gave a flower a new name. This was the red hibiscus, which when crushed, was used to make a dark purple dye used for blackening shoes. Thus, it came to be called sapattu mala or shoe flower. It was formerly known as vada-mala or ‘execution flower’, since executioners wore it.

Skirt

guess.com

Skirts in the modern sense were first introduced by the Portuguese. Prior to this, local women simply wore a piece of cloth from waist to ankles that was wound around the loins. Saaya, the Sinhala word for skirt, comes from the Portuguese saia or skirt, petticoat, and gown. Although local Muslim women do not wear skirts, they too have borrowed the Portuguese saia to refer to the underskirt which is worn under the saree. They call it saaya or more properly ul-saaya (or inner skirt).

Hats

pxhere.com

Headgear was certainly known among Sri Lankans from very early times. Not only did the Moors who were Muslims wear various kinds of caps, but the Kandyans of old did so too. Robert Knox in his Historical Relation of Ceylon (1681) describes Kandyan country caps as being fashioned like mitres, with two flaps tied up over the top of the crown. They were either white or blue in the case of high caste men and of different colours among the more humble castes. Such caps were usually known as toppi, which is a loan-word from Tamil.

However, the hat with its characteristic brim seems to be an European introduction. It is possible that hats were known even before the British took control over the entire country in 1815. John D’Oyly records in his diary that on June 1812, the Kandyan king presented karuppus toppi (or white round hats) to the Dukgannaralla or courtiers. The word evidently comes from the Portuguese carupuça or cap. Carupuça has been defined in lexicons as ‘a cap to keep from cold and sun-burning’ (Dictionary of the Portuguese and English Languages, Anthony Vieyra, 1813) while in Madeira, carapuca to this day refers to a brimless wool cap that fits closely to the head. However, it is possible that in the olden days it did mean a hat with a little brim around it. Kandyan temple paintings such as in the Temple of the Tooth depict men wearing white headdresses with a rather unusual upturned brim. Perhaps this is why D’Oyly referred to it as a hat.

Necktie

rebeatmag.com

Contrary to popular belief, the necktie didn’t come with the British. The earliest neckties were very likely introduced by their Dutch predecessors in the 17th century. The tie was known among the Sinhalese of old as dasiya. For instance, in Charles Carter’s Sinhalese- English Dictionary (1924) we find dasiya being described as necktie and neckerchief. The word has its origins in the Dutch dasje or neck-cloth.

Constance Gordon Cumming in her book Two Happy Years in Ceylon (1892) refers to the half-native, half-Dutch dress of low-country Sinhalese headmen as a long Dutch-looking official coat of dark blue cloth with large gold buttons, a white waistcoat displaying gorgeous buttons and silk neck-tie. So there you are, the fashion of wearing ties started with the Dutch!

What we can conclude from all this is that European dress, although introduced a long time ago and from lands far away, has transcended time and space to add life and color to the fabric of local sartorial elegance.

Cover image: lankapura.com