Sri Lanka is home to 21 million people, 19 ethnicities, and four officially recognized religions. For the longest time, however, there were no official records of most of the island’s ethno-religious minorities. The ones we know about are the Sinhalese, Tamils, and Moors, given that they are taught in school. Everyone else—who make up two percent of the population—is categorised as ‘other’.

Who though, are the ‘other’s? In January this year, the Ministry of National Co-existence, Dialogue and Official Languages released People of Sri Lanka, a publication which officially documents all ethnic communities in the country.

In this two-piece series, we’ll be taking a look at the ‘other’ 2%: the minority otherwise overlooked. Click on the titles for longer pieces of the communities already featured by Roar Media.

The Parsis of Sri Lanka

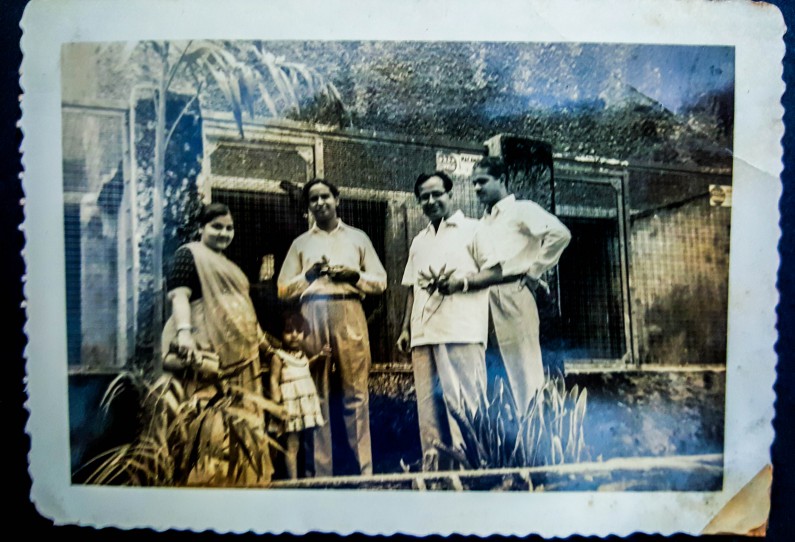

Gathering of Parsis outside Parsi Club, c.1940s. Those were the days when there were about 200 Parsis here before the Swabasha policy in the 1950s spurred many to migrate. Image courtesy Aban Pestonjee.

Remember the Khan Clock Tower in Pettah? The landmark monument, standing right across the iconic Hunters building, was constructed by one of Colombo’s oldest Parsi families. Despite being one of the country’s smallest communities, their contributions are quite the opposite: from leading the construction of Sri Lanka’s first cancer hospice to chairing the Abans Group.

The community, however, is miniscule and consists of only about 40 people in total.

Having initially migrated due to persecution of their faith, the community emigrated from Persia to India and the East over ten centuries ago. They landed in Sri Lanka for trade around the late 1700s, before establishing themselves in Colombo as business leaders.

The Bharatha Community

A sea-faring group from South India also known as ‘Paravar’, it is said that the Bharathas were recruited by coastal Sri Lankan kings to strengthen their armies. This was apparently between 12-15 AD, though there are no solid sources to confirm when they first arrived to the island.

According to People of Sri Lanka, the two main Bharatha groups consist of the sea-faring people settled along the Chilaw-Colombo stretch, and those who were brought down by the British to work in the Colombo harbour and are now settled in and around Kotahena.

Though Bharatas are ancestrally Hindu, many of them converted to Catholicism and took on Portuguese names shortly after Portuguese missionaries arrived in Sri Lanka.

As of 2011, there were 1,688 Bharatas in the country, though this may be an inaccurate estimate as many families in the North and East register themselves as Sri Lanka (Ceylon) Tamil.

Verdas: The Coast Veddas

Believed to be a semi-nomadic tribe, the Coast Vedda’s settlements are mainly along the East Coast between Trincomalee and Valachchenai. A population numbering 2,460 as of 2015, most of them are native Tamil speakers, and claim to have no ties with the other vedda communities in Sri Lanka.

The Verdas means of livelihood is laborious: from day labour, to fishing, animal husbandry and agriculture. They are also honey-collectors, an activity limited exclusively to the menfolk. The women are mostly housekeepers and tend to cooking and child-care, even though a few engage in fishing and agriculture as well.

The Veddas

The chief talks to another Vedda about the drumstick harvest. Photo by Thiva

According to legend, the Veddas result from the incestuous relationship between Vijaya and Kuveni’s children. The children, having run away to the jungle after their mother was rejected by her consort and tribe, managed to survive in the jungle and eventually procreated to beget the line of Veddas present today. However, academics state otherwise: they believe that the Veddas are mixed group of humans dating back to the stone age.

Currently, the community has broken off into three identifiable groups: the niri vedda (naked vedda), kola vedda (those who wears leaves), and gam vedda (those who have embraced modernity to a certain extent).mModernisation and assimilation have played major roles in disrupting their traditional lifestyle, and has compelled part of their community representatives to request their rights be included in any new constitutional reforms.

The Sri Lankan Kaffirs

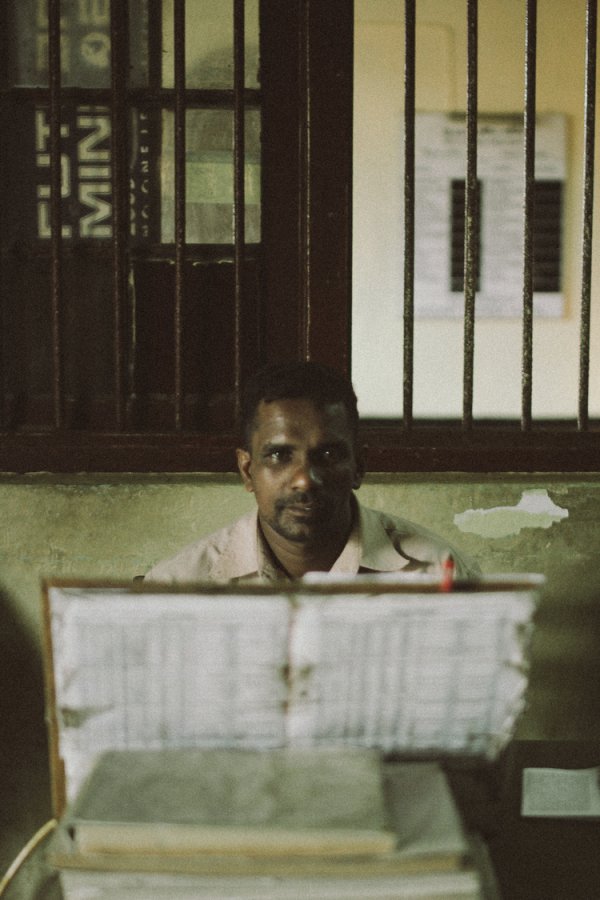

M.J. Emeliyana, 83: “The White man brought our grandfathers down to fight the war.” Out of everyone here, Emeliyana holds the oldest memories, and is the only person of her group who can speak both Tamil and Sinhala. Photo by Thiva.

Originating from East Africa, the Kaffirs were brought to Sri Lanka not just by Arab and Portuguese traders of old, but also by the Dutch as slaves. Additionally, the Dutch and the English brought thousands upon thousands of these East Africans to strengthen their regiments while in Sri Lanka. However, their numbers currently stand at 1,500 or less today. Many are said to have returned to their native lands, or perished during numerous battles which took place in Ceylon’s past.

Concentrated around the coastal areas, the Kaffirs of Sri Lanka are scattered around Sirambi Adi in Puttalam, Pallai Uththu in Trincomalee, and in Kalpitiya, Batticaloa and Negombo. A unique characteristic amongst the community—many who have now intermarried with other Sri Lankan ethnicities—is the fact that some of them speak in Portuguese Creole in addition to Sinhalese and Tamil. They’ve also carried forward a tradition of song and dance particular to their culture, known as Manja.

The Dutch Burghers

Interestingly, the Dutch first arrived in Sri Lanka as a Chartered Public Company, the VOC, (Vereenigde Oost- Indische Companie) also known as the Dutch East India Company. King Rajasinghe VI sought their assistance to drive out the Portuguese who were in Ceylon at the time.

The early 1950s were considered the ‘Burgher Zenith’, where there were numerous professionals in nearly all aspects of public service. Burghers held senior positions and “virtually ran the railways, customs, inland revenue, and port.” However, things changed abruptly with the Sinhala Only Act in 1956. Largely English educated, Burgher government employees were compelled sit for Sinhala proficiency tests and many failed. With English Medium classes also being done away with, many Burgers felt unwelcome and emigrated to Australia, the UK, and Canada. Those who chose to stay have assimilated, and learnt Sinhala.

The Portuguese Burghers

Photograph of a Burgher wedding from long ago. Image courtesy: easternsrilanka.natgeotourism.com

The union between the Portuguese and local communities saw the birth of Sri Lanka -Portuguese Creole, which was used in the island from the 16th Century to the mid 19th century. This is still used in certain areas of the country, especially by a segment of the Batticaloa Tamils and the Kaffirs.

Most of them are craftsmen, as they carried on skills left over by their ancestors: one would find blacksmiths, key makers, printers, tailors, master carpenters and mechanics to name a few. Strong Catholics, the Portuguese Burgers are more often than not indistinguishable from their Sinhala, Tamil, and Moor neighbours in terms of skin colour and language. Unlike the Dutch Burgers, the Portuguese were not against intermarriages; when forming their colonies, Portuguese men married Sinhala and Tamil women, creating ‘Mestiços’: an Euro-Lankan mix who were ostracised by the Sinhalese, Dutch, and British in future generations, but whose descendants are the Portuguese Burghers of today.

The Burgher population (of both Portuguese, Dutch, and other European mixes) number to 38,000 according to the census carried out in 2012.

The Sindhis

Priests conducting a pooja at the temple. Image courtesy Aisha Nazim.

Originally hailing from the Sindh province in what is currently Pakistan, the Sindhis were displaced during the Partition in ’47. They settled in North India, and then eventually moved to different countries, including Sri Lanka, where they had a reputation for trade. There are approximately 500 Sindhis in Sri Lanka, mostly concentrated in Colombo. Numbers continue declining due to their practice of marrying within the community; the lack of options within Sri Lanka has resulted in Sri Lankan Sindhis marrying abroad.

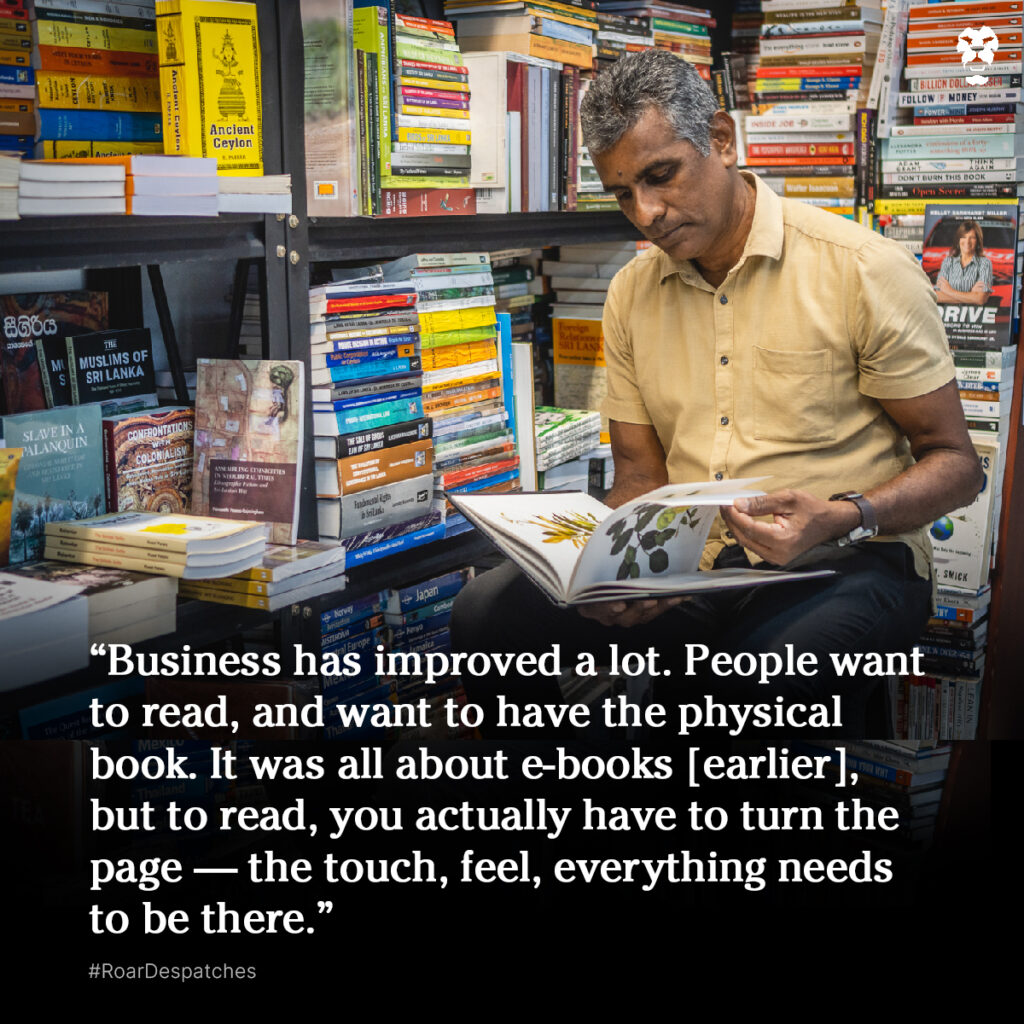

The Sindhis first arrived in the mid 1800s for trade. They established themselves around Fort and Pettah, selling silks and artefacts before becoming wholesale businessmen. Currently, many Sindhis still work in three main business sectors: hotel, industry, and retail.

Stay tuned for part II, where we will explore more Sri Lankan minorities.

Cover image courtesy: Naresh Moorjani