Looking small and rather faded underneath the transparent protective covering, the stamp appears pretty unremarkable. A dull pink in colour, with the profile of the Queen Victoria’s head standing in the center, it even lacks the perforations which we are so used to seeing in stamps. However, there is nothing ordinary about this little piece of paper at all: it is nearly 159 years old, costs thousands of pounds, and is the sixth stamp to be issued in Ceylon.

Known among philatelists as the “Dull Rose”, this is the rarest and most expensive stamp to be issued in Sri Lanka. “This one cost me £4000,” says Dulshan Ellawela, as he sits amidst his extensive collection of stamp albums. “A mint copy would cost thousands of pounds more.”

Dulshan Ellawela has been an avid philatelist for over two decades. “I am not an expert,” he laughs, but he acknowledges that twenty years of collecting stamps has kept him well informed about philately. In fact, he is even currently pursuing a Phd related to the subject, and has published a stamp catalogue showcasing Ceylonese stamps issued during its pre-independence period.

The elusive Dull Rose. Ironically, this stamp, along with every other Sri Lankan item in his extensive philatelic collection, was obtained from the UK. “I haven’t got a single stamp from here,” he explains. “Since Ceylon was a British colony, all the stamps from the pre-independence period were printed in Britain, and most of the good collections belong to British people.” Credits: Thiva Arunagirinathan

“This is Ceylon’s first stamp,” points out Ellawela, gesturing towards a nondescript purple-brown stamp. Issued in 1857, just 17 years after the world’s first postage stamp was out, it was valued at 6 pence and was used to send a half ounce letter from Ceylon to England. Since Sri Lanka was a British colony at the time, the stamp was printed, designed and issued in Britain by a company called Perkins, Bacon & Co. a notable printer of books, postage stamps and banknotes.

It lies in the album with several other stamps from the Queen Victoria period, and apart from very slight variances in colouration, it appears hardly discernible from the others. So how would an interested laymen identify it? By simply turning the stamp over, it turns out.

“This stamp is made on something called blued paper,” says Ellawela, pointing out the faint bluish tinge at the back of the stamp. “It has also go a distinct star shaped watermark.” Credits: Dulshan Ellawela

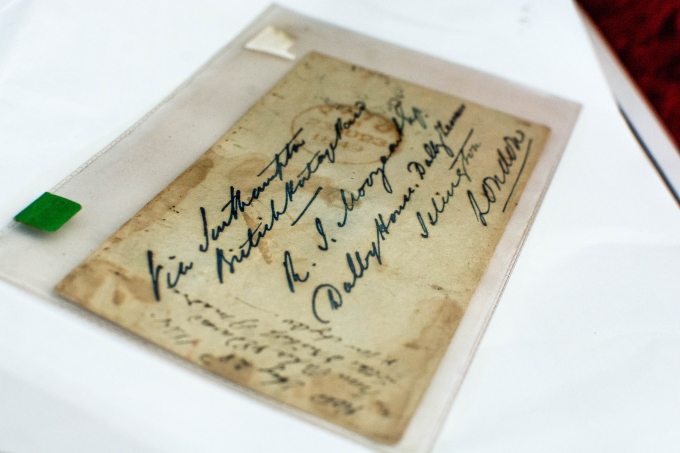

Pre-stamp era! A letter which once travelled from Galle to London before stamps were even invented. Back then, it was the person who received the letter who had to bear the cost of postage.Credits: Thiva Arunagirinathan

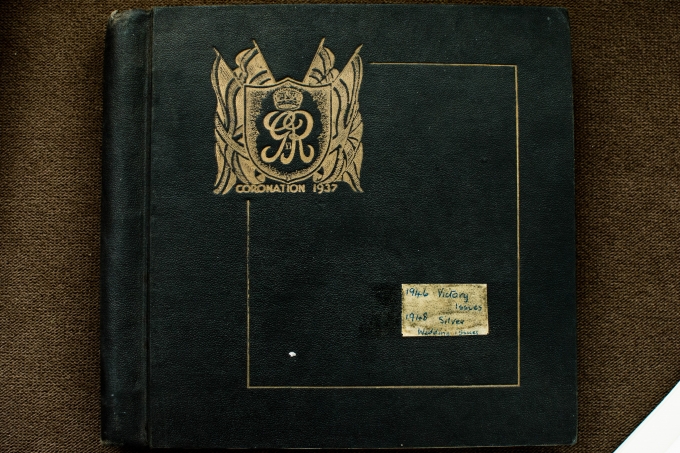

One of Ellwela’s many stamp albums. The word ‘philately’ originated from the Greek words philio (which means “I love”) and ateleia (which means “free of charge”). This simply refers to the fact that stamp collecting was an inexpensive hobby, since the recipient of a letter is free from any affixed delivery charges. However, seen in present day context when stamps could cost thousands of dollars, it is a little ironic. “If you want to be a real collector, you have to be a millionaire,” Ellawela laughs.Credits: Thiva Arunagirinathan

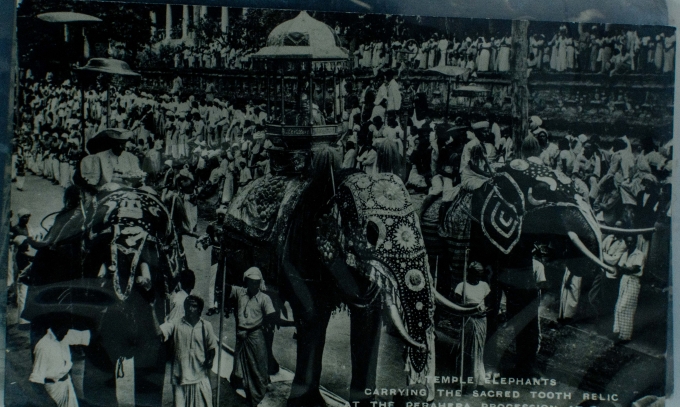

A photograph postcard from the early 19th century. Most people are of the idea that philately just flatly means stamp collecting, which is probably why it is so often relegated to the category of the ‘nerdy’ hobby. But the truth is, you can be a philatelist without owning a single stamp. For instance, philately is also covers postcards, postmarks, revenue stamps, or anything at all related to postage or postal history. Credits: Thiva Arunagirinathan

An unused letter cover from the Queen Victoria period. With its beautiful embossed seal and the net-like material inside (which we felt when we touched the insides at Ellawela’s insistence), it puts our present day envelopes to shame. Credits: Thiva Arunagirinathan

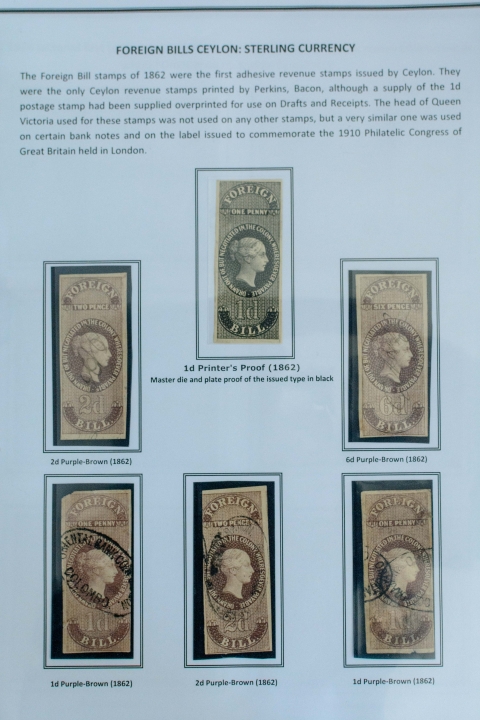

Some revenue stamps from Ellawela’s collection. “In those days, there were two kinds of stamps, postal stamps and revenue stamps,” he tells us. “They may look similar to postage stamps, but these were used for revenue purposes, like, for example, to collect taxes or to pay fees or for legal matters.” Credits: Thiva Arunagirinathan

Archiving Sri Lanka’s history through stamps. “The issue here is that people don’t give a proper idea to children. They look at stamp collecting in the same way they look at collecting stickers or pressed flowers. But there is a lot more to philately that just that.” Credits: Thiva Arunagirinathan

Philately may seem like an extravagant indulgence and one of those ‘uncool’ hobbies which people scoff at, but in truth, a country’s stamps can tell a hundred stories about its history, culture, landscape and society, making philately doubly fascinating. Besides, stamp collecting is for everyone. Of course, you will probably never be able to get your hands on that mint copy of a Dull Rose, but there are probably thousands of stamps you can get hold of without burning a hole in your wallet.

Cover image shows some of Ellawela’s Ceylonese stamps from the Queen Victoria collection. From 1857 to 1870, the stamps issued were in pence and shillings. The stamps issued after 1872 were in rupees and cents, even though they continued to be printed in the UK. The stamp with the white edge around it is called a printer’s proof. “Before printing the actual stamp, printers used to make a ‘proof’ to check if the stamp is coming out correctly,” explains Ellawela. Credits: Thiva Arunagirinathan