We take for granted the immense politics we express through our bodies in the day to day. From the clothes we wear and the tone of our speech to our mannerisms and gestures, our public physical expression manifests intricate networks of learnt behaviour from some status quo or other. This is true whether we choose consciously or not to conform, rebel, subvert, or build on from these models.

Shakti: A Space For The Single Body

This year, Colombo Dance Platform (CDP) staged ‘Shakti: a space for the single body’, a double weekend of artistic ruminations on body and gender as performed by several international solo artists. Shakti makes a timely appearance in light of several recent events concerning the policing of women’s bodies in public.

Draping A Straitjacket

Janani Cooray: Osariya. Image credit: Malaka MP for Goethe-Institut Sri Lanka

Janani Cooray: Osariya. Image credit: Malaka MP for Goethe-Institut Sri Lanka

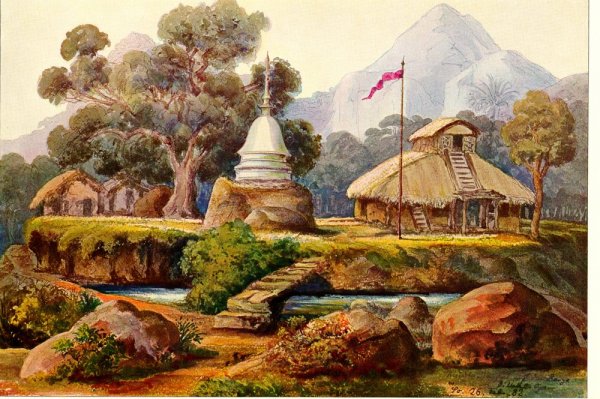

The opening act was integrated into the traditional lighting of the lamp. Janani Cooray, a performance artist, ambled across the floor in front of the stage in an osariya. Her Osariya (the title of the piece as well) had a jacket and underskirt made of pieces of metal bent together, while the sari that draped over this was made entirely of barbed wire. She walked across in constrained, robotic movements, the creaks of the metal jarring our aural senses as her physical movements jarred our sense of mobility.

Cooray’s commentary on the restrictions of tradition resonates with the recent spotlight in international media about the policing of mothers’ attire when they pick up their children from school. One of the main points of contention rests on the issue that saris, while deemed ‘decent’, in fact, reveal far more of a woman’s body than other attire that have been prohibited. This donning of the sari thus becomes far less about sexuality than it does about nationalism, ethnic politics and patriarchy. It is inherently a matter of restricted mobility: those who do not conform are limited in their ability to pick their children up, to perform functional tasks. Similarly, Cooray’s performance highlighted restricted mobility due to her attire but, more importantly, if she were to step a toe out of line in her barbed wire sari, the consequences would be violent.

Gender Bending

Sithara Maduwanthi belongs to Sri Lanka’s first all-female drum ensemble, Thuuryaa. Image credit: Malaka MP for Goethe-Institut Sri Lanka

Sithara Maduwanthi belongs to Sri Lanka’s first all-female drum ensemble, Thuuryaa. Image credit: Malaka MP for Goethe-Institut Sri Lanka

A satirical news piece responded to the issue about mothers’ attire at school by reporting a ‘conundrum’ as a father dressed in a pencil skirt came to pick up his child. The commentary is that these skirts are not allowed for mothers – should they be allowed for fathers, who have no outlined code of attire? This jest at cross-dressing touches upon more than just the double standards applied to men and women. It highlights as well the mere performance of gender: that gender is extraneous to self and performed through various expressions of the body and its accompaniments, such as attire and mannerism. Two fascinating pieces at CDP explored this in very different ways.

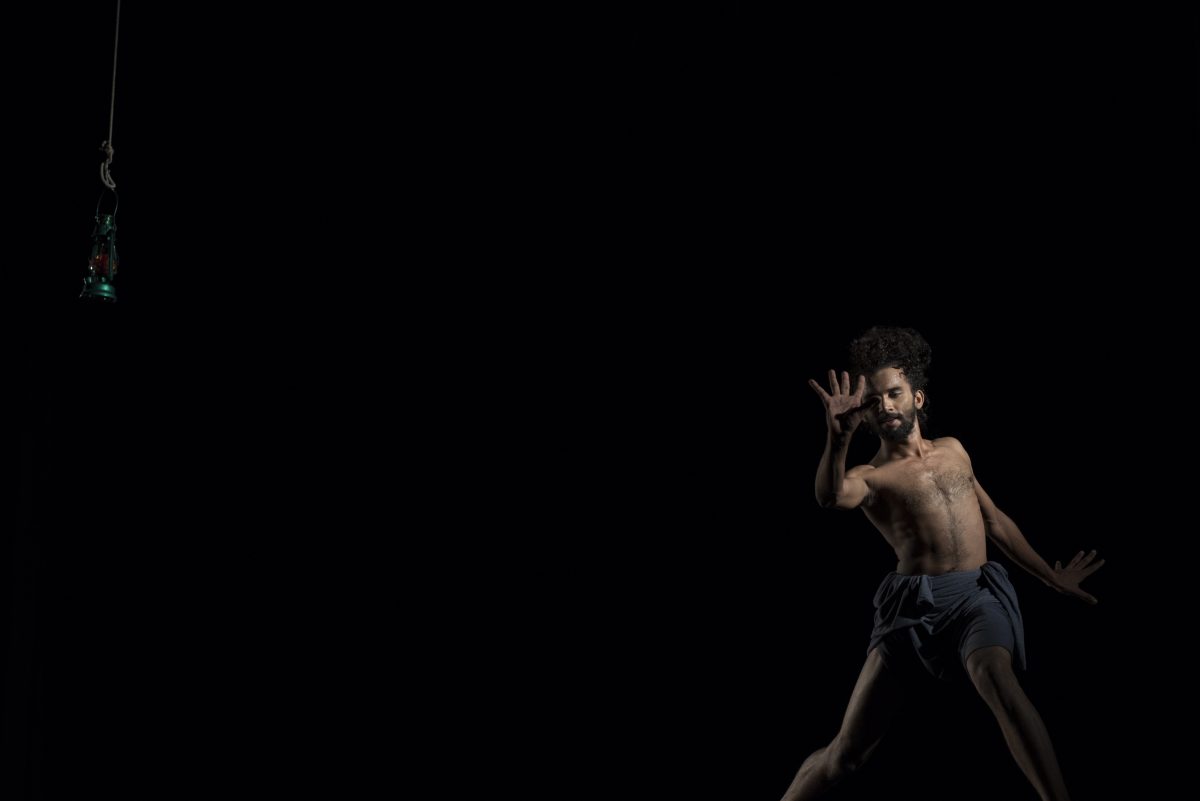

While ceremonies were taking place, we could hear the traditional beats of drums coming from off the wings. Once formalities were done, a spotlight shone on the drummer. To our surprise, it was a woman. Sithara Maduwanthi is part of Sri Lanka’s first all-female drum ensemble, Thuuryaa. Her sudden appearance onstage shook the audience’s assumption that the drummer would be male. A simple gender reversal, yet it fundamentally questions who traditionally can and cannot use their bodies to perform certain tasks.

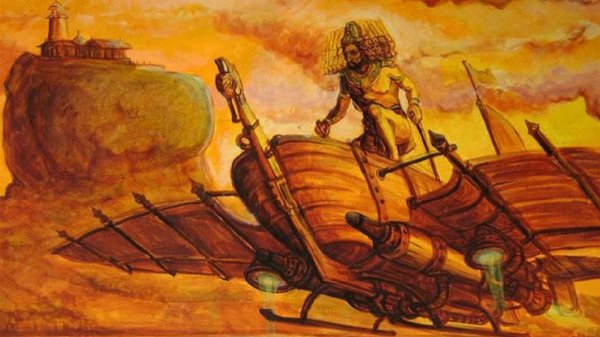

Pradeep Gunarathna staged Giri Devi Androgynous, which was originally titled ‘Gara|Giri’. His performance was a creative take on two ritual dances, where he moves between embodying both the giri yakshani (demoness) and the giri devi (goddess). The conflict between the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ female figures is expressed not only through Gunarathna’s tense, uncomfortable movements but through the conflictual expression of feminine dichotomy through the male body. In fact, this performance calls into question our expectation of deific femininity, for what really does ‘feminine’ mean in the spiritual world? His performance resonates with Judith Butler’s thesis that ‘Gender is an impersonation… becoming gendered involves impersonating an idea that nobody actually inhabits’.* Even the original title highlights the arbitrariness of gender attribution in the linguistic variation of ‘a’ and ‘i’ to mark female and male deity. These subtleties, natural to those familiar with the language, are learnt behaviour, part of a matrix of accepted linguistic signs that are inextricable from gender politics.

Pradeep Gunarathna’s Giri Devi Androgynous. Image credit: Malaka MP for Goethe-Institut Sri Lanka

Pradeep Gunarathna’s Giri Devi Androgynous. Image credit: Malaka MP for Goethe-Institut Sri Lanka

Cultures And/Of Consumption

Gender issues were not the only focus of the performances, though. Mirra’s According to official sources exaggerated the physical markers and movements of bodies reproducing commercialism. Spraying the room with perfumed deodorant, wrapped in electrical wire, and strutting a catwalk in mindless rounds, Mirra’s exaggerations were eloquent reproductions of our everyday bodily expression of consumerist values.

Later, in the panel discussion, both Mirra and Pradeep discussed the onus placed on non-European performers to somehow involve their own ‘culture’ in their performances. While Pradeep expressed that he felt no such pressure to represent Sri Lankanness, Mirra, trained in contemporary dance, stated that she had often faced feedback asking about her Indian work. In sharp response, Mirra says, ‘Well, I’m an Indian. And I work. So I produce Indian work, right?’

In According to official sources, Mirra incorporated distorted yogic movements and poses that added a sense of disrupted energy to the dance. This broken natural energy worked well with the dance’s thematic but is it possible for her, as an Indian performer, to use this as a culturally neutral form of movement? Or will her body be ever interpreted as channelling Indianness when expressing itself through yoga? Is it even necessary to aspire to cultural neutrality in the first place?

Trappings Of The Body

Our physicality, both natural and chosen attributes, constitutes part of a wider domain of signs that communicates the politics of the world around us. While we see ourselves reflected, distorted, exaggerated in stage performances, we hardly acknowledge that the everyday is a performance in itself. We may attempt to disrupt accepted notions in order to escape the status quo: wearing androgynous attire to bend gender ideals, ironically donning traditional attire, assuming different accents, refusing to ‘sit’ properly. Whatever these rebellions are, as Butler says, ‘this is not freedom but a question of how to work the trap that one is inevitably in’.*

*Judith Butler. ‘The Body you Want’. Interview with Liz Kotz. Artforum. November 1992