Sri Lanka, with its many names bestowed upon it by its many visitors, has always been a land of diversity. The following article is the second in a two-part series exploring the lesser-known inhabitants of Ceylon in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Egyptian Exiles

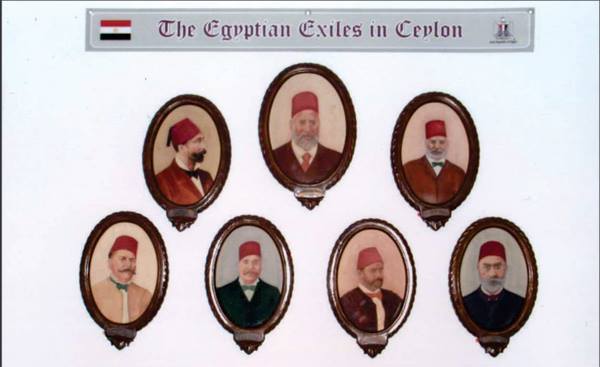

Portraits of the Egyptian Exiles who made it to Ceylon adorning the walls of the Orabi Pasha Cultural Centre, Kandy. Image courtesy Facebook/Orabi Pasha Educational Institute

Ever wondered how Orabi Pasha Street in Colombo got its name? We have an Egyptian revolutionary, who was banished from his home country in 1882, to thank for it. Orabi Pasha seemed to have received a warm welcome. The Muslim community, in particular, having a racial identity as descendants of Arab traders, had gathered to get a glimpse of the exile who was to spend his life in Ceylon until 1901. He was said to have divided his time between Kandy and Colombo.

The Egyptian exiles were able to maintain friendly relations with the Ceylonese Muslims, to the extent that local Muslims embraced neo-Ottoman fashions, such as Egyptian trousers, and the fez (the Tarboush). The exiles also developed modern schools for Muslim children. Thus, Zahira College in Maradana came to be the first Muslim school in the country. However, the exiles are believed to have found the tropical climate of Ceylon rather unpleasant, and they frequently fell ill, sometimes fatally so. Hence, some were pardoned and returned to Egypt.

In 1983, to commemorate the centenary of Orabi Pasha’s arrival, Maradana Street was renamed Orabi Pasha Street.To reciprocate, a road in Cairo was christened Sri Lanka Street.

Jews

Portrait of the only identified Jewish woman in Ceylon (1870s) in traditional Jewish attire. Image courtesy haruth.com

An orthodox Jew walking to the Chabad Jewish Synagogue located in Colombo would be a rare sight today. However, the fading trail left by the Jewish presence in Ceylon can be traced back to scholarly allusions of the 9th-century Muslim traveller, Abu Za’id al-Ḥasan Sirāfī, and the 12th-century Muslim cosmographer al-Idrīsī. The latter is said to have noted, in his Scriptorum Arabum de Rebus Indicis Loci, that among the official viziers representing religious tolerance were four Jews in the royal residence, Aghna, of the Ceylonese king. This website states that the Sinhala king was likely to have been Kasyapa IV, although no further comments have been made.

More so, we turn to biblical references of the affluent King Solomon, who wielded in Occupied Palestine (now Israel) from 970 to 931 BC. His rich trade history included the ancient seaports of ‘Ophir’ and ‘Tarshish’ (1 Kin 10:22). Interestingly, scholar Samuel Bochart suggested the probable site of “Cape Comorin” in Tamil Nadu India as ‘Ophir’, and “Kudiramalai” in Ceylon for ‘Tarshish.’ These places were said to have been abundant in ivory, peacocks, gold, and pearls. Now comes the question: did King Solomon keep close ties with Sri Lanka and India through trade? If so, could there be a possibility of the Jewish descendants of Solomon’s era settling here? According to the Vishwakarma community, it is stated the Tamils, particularly, of this caste, hold Jewish lineage with a sub-group of goldsmiths known as Thattar Jews, who exalted in wealth and power. Even if transactions with Kerala, housing the oldest Jews in India, brought Jews to the island under the Dutch East India Company, some sources attest gold and silver were scarcely products of Ceylon.

Still, the 19th century saw European Jews arrive in Ceylon, resulting in coffee plantations once run by the Wormser Brothers in places such as Pussellawa.

Mudaliyar

British-appointed native Mudaliyars and a British official, from Tangalle in Southern Sri Lanka. Image courtesy: karava.org

The word Mudaliyar is derived from the Tamil ‘mudhal’, which translates to mean ‘the first’. This class of people was meant to create an alliance between the European imperial administration and the local proletariats—similar to South India. Native chieftains were carefully selected by the rulers, leading to the polarisation of class status.

The mudaliyars were mainly engaged as tax collectors, translators, and maintainers of the rajakriya compulsion, and law and order on a local level. By gaining a position that elevated them from the masses, they were easily recognisable as headmen. They even had a dress code to accentuate their status, coming second only to the Europeans. As this website informs, a mudaliyar would appear in uniforms consisting of Somana cloth, a long coat with a belt made of gold or silver lace, and be equipped with a short kasthana sword.

Although they didn’t receive a salary, the mudaliyars enjoyed ample estate lands that they were endowed with.¹ More broadly, as Yasmine Gooneratne notes in The Mudaliyar Class of Ceylon: Its Origin, Advance, and Consolidation (1970), “their lives were leisured [and] their tastes and interests very nearly identical with those of the English upper classes in the same period.”

A prominent member of the mudaliyar community in Ceylon was Gate Mudaliyar Jeronis de Soysa (1797-1862), who left a deep imprint on many fields, including coffee plantation and ayurvedic therapy. Known as the ‘father of private enterprise’, he was ardently involved in reservoir constructions, and was the driving force behind large-scale road building projects in the upcountry areas that were once laden with jungles. Formerly recognised as the tallest building in Ceylon, the Holy Emmanuel Church in Moratuwa was built after de Soysa’s late conversion to Christianity. He was also the first mudaliyar to be recognised for his philanthropy.

Nautch Dancer

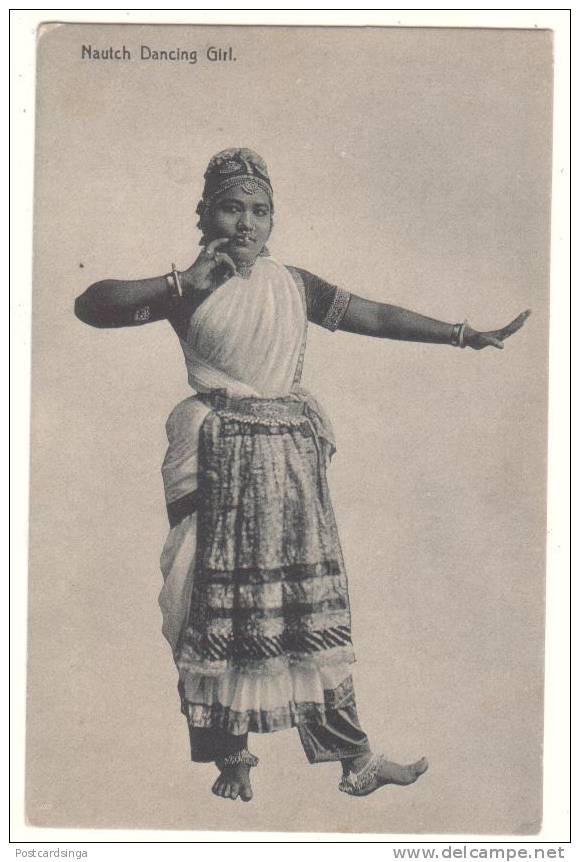

A nautch dancing girl from Ceylon. Image courtesy delcampe.net

Nautch (or dance), an Anglicised Hindi/Urdu word, was a favourite among the memsahibs of India. South Indian nautch girls, on the other hand, mainly performed at temples. In Ceylon: A General Description of the Island, Historica, Physical, Statistical (1876), Horatio John Suckling claims that the arrival of nautch girls to Ceylon may have been owed to the influence of Buddhism. Lavishly swathed “in a number of yards of rose-coloured muslin edged with gold tinsel” and jewellery, these girls were accompanied by two men who would provide the music, “one having a ‘tom-tom’ fastened to his waist” and the other playing “an Indian guitar.” From a European perspective, they were described as “very stupid” and “unmeaning exhibitions,” but they were “perfectly bacchanalian” in the eyes of a fully native audience.

Parsi

Portrait of a Parsi man. Image courtesy: imagesofceylon.com

More than 1,000 years ago, Persian Zoroastrians arrived in the Indian subcontinent, in an attempt to flee religious persecution that followed the Muslim conquest of Persia.

Parsis have been known for paving the way for education and entrepreneurship, although their community in Sri Lanka had dwindled to only 61 individuals by the year 2006.² The early 19th and 20th centuries saw the Indian Parsis sail to our island, mainly for trade.

Some prominent members of the community include Sri Lankan-born Avabai Bomanji Wadia (1913-2005), who hailed from an upper-class Parsi family with roots in Gujarat. Wadia became the first Sri Lankan woman to achieve honours in the bar examinations and pursue a career in law.

Of the historic clock towers in Colombo, the one in Pettah, at the entrance to Pettah Market, was built in the early 20th century by a Bombay Parsi family who owned oil mills in Ceylon. Little is known about the Parsi descendants who called this island their home.The renowned political figure Kairshasp N. Choksy (1933- 2015) once served as Cabinet Minister of Finance under Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe from 2001 to 2004. Other prominent Parsis also include multi-billionaire Sohli Captain of the megacorp John Keells Holdings Limited, and Aban Pestonjee, the chairperson and founder of the Abans empire. Hailing from humble beginnings, Pestonjee began her career servicing customers from her home. Her company evolved to be one of the first firms to introduce Korean home appliances to Sri Lankan consumers.

Indeed, outside the little body of knowledge, there remains the lasting impact made by Sri Lanka’s many adopted children. Although they may not always be acknowledged in history books or museums, their culture is deeply embedded in the Sri Lanka we see today.

Further sources:

¹ From Coffee to Tea Cultivation in Ceylon, 1880-1900: An Economic and Social History, Roland Wenzlhuemer (2008)

² Parsis in India and the Diaspora, edited by John Hinnells, Alan Williams (2008)

Featured image courtesy Lankapura.com