“Yes, there will be winter, there will be cold, there will be snowstorms, but then there will be spring again.”

Anyone who reads Sri Lankan Sinhala literature will be very familiar with these lines from The First Teacher by Chingiz Aitmatov. Translated as Guru Geethaya in Sinhala, it has for long been among the most popular books in Sri Lanka over the years. In fact, translations of Russian literature are among the most popular books in Sri Lanka, according to Sirimanna Karunatillake of the Soviet-Sri Lanka Friendship society and the Russian Literary Circle of Sri Lanka. This popularity has remained unwavering despite Sri Lanka’s British English influence and the spread of anti-Russian sentiments from the West. Karunatillake said to Roar, “English is very close to us. We are in fact an English colony. We learned in English and our thoughts were shaped by English. Yet, how little has English literature penetrated into Sri Lankan literature? But Russian Literature If you ask anyone if they have read Maxim Gorky, Tolstoy Anton Chekhov [in translated form] they will say, yes.”

Beginnings

Professor Tissa Kariyawasam writes in the Sri Lankan Sinhala magazine ‘Soviet Deshaya’ (The Soviet Union) that since English literature was so closely tied to the ruling class, it was Russian literature that first connected with the public of Sri Lanka. In January of 1932, the Silumina newspaper began a series of articles on Russian literature. The Vesak issue of the Dinamina newspaper of 1940 published a work of Leo Tolstoy translated into Sinhala by Charles Justin Wijewardena. In his book ‘”Sri Lanka – Soviet – Russia Relations As I Happen to Know’” Sirimanna Karunatillake also confirms that in 1944, Ediriweera Sarathchandra and A.P. Gunarathne published a collection of translated Russian short stories of Chekov, Gorky, Tolstoy and Sologub. It was followed by similarly published translations by K.D.P. Wickramasinghe in 1946 and by Cyril C. Perera in 1947 and 1950. This was the initial trickle of Russian literature into Sri Lanka. Cyril C. Perera would translate and publish so many Russian works of literature that he received recognition from the Union of Soviet Writers and the Russian Embassy in Sri Lanka for fostering relations and services to literature.

From Sri Lanka To Russia, And Back

The initial steps towards more extensive literary relations were taken after the establishment of formal diplomatic ties with the Soviet Union in 1957 by none other than Sri Lanka’s great Sinhala writer Martin Wickramasinghe. In a book written by Vladimir Yakovlev—the first Soviet ambassador to Sri Lanka—on his experiences in the country, he states that he was fortunate to meet Sri Lanka’s premier author and they were fast friends. He would later introduce Wickramasinghe to Nikolai Semenovich Tikhonov; a Soviet writer, member of the Serapion Brothers literary group, once chair of the Union of Soviet Writers and the Soviet Peace committee as well as a recipient of the Lenin Peace Prize. Yakolev writes how Wickramasinghe began his love of Russian Literature with English translations of Gorki, then Gogol, then Chekov and anything else he could find. To which Tikhonov replied saying that, ‘now (in 1957) a favourable environment has appeared in which to develop cultural relations between the two countries,’ inviting Wickramasinghe to visit Russia, and further said that Wickramasinghe’s books need to be translated and published in Russia. All of which was heartily agreed to by Wickramasinghe who would send English translations of his work to the Embassy later on.

Wickramasinghe would eventually make four visits to Russia, exploring the country and making connections with literary circles. He would go on to write the book ‘Rise of the Soviet Union’ based on his experiences which explores the new Russia he encountered from multiple angles. In it, he also says, “I feel that by reading these [Russian] novels and French novels, I received the experience and wisdom of living a hundred years as a lay person. I did not feel that I received the same experience and clear knowledge of life and faith in humanity regarding a lay person’s life, from French and English novels, the way I received it from old Russian novels.” By this time a collection of Wickramasinghe’s short stories and the novel ‘Madol Duwa’ were being published in Russian to a favourable reception. In W.A. Abeysinghe biography of Martin Wickramasinghe, he writes of the recollections of Vladimir Baidakov who was the first secretary of the Soviet-Sri Lanka Friendship Society who said “I got to know Martin Wickramasinghe in 1959 after reading his collection of short stories and the novel “Madol Duwa”. They became very close to my heart because of the amicability, honesty, the strength to look deep into the human mind and the author’s affection and kindness towards the public. In later years Wickramasinghe’s major works would be published in the Soviet Union to great acclaim in literary circles.

Sirimanna Karunatillake writes that the path opened by Wickramasinghe’s tours in Russia allowed other Sri Lankan writers to follow suit. For example; A. V. Suraweera, K. Dissanayake, Ven. Udakandawala Saranankara, W. A. Abeysinghe and Gunasena Withana. Writers such as these had close relations with the Soviet Union. Even attending major cultural and literary events in Russia at the invitation of institutions like the Union of Soviet Writers. Many of these writers were working off English translations and writing Sinhala translations from them. But after diplomatic ties were officially established quite a few Sri Lankan writers came to study at Russia’s “Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia.” Better known as Lumumba University. With their acquired knowledge of Russian, they began to write Sinhala translations from the original publication itself. These were writers like Padmaharsha Kuranage. Kuranage was an editor of the popular Sanskruthi cultural magazine in Sri Lanka that introduced many foreign authors to the Sri Lankan public. He also published a book of translated Russian short stories in that time. He was one of the first batches of Sri Lankans to study at Lumumba and proceeded to continue with his translation work there. He received offers from Russian publishers to print these translations as well. And so began a publishing relationship that lasted from 1960 to 1992 as Kuranage settled in Russia till the fall of the Soviet Union.

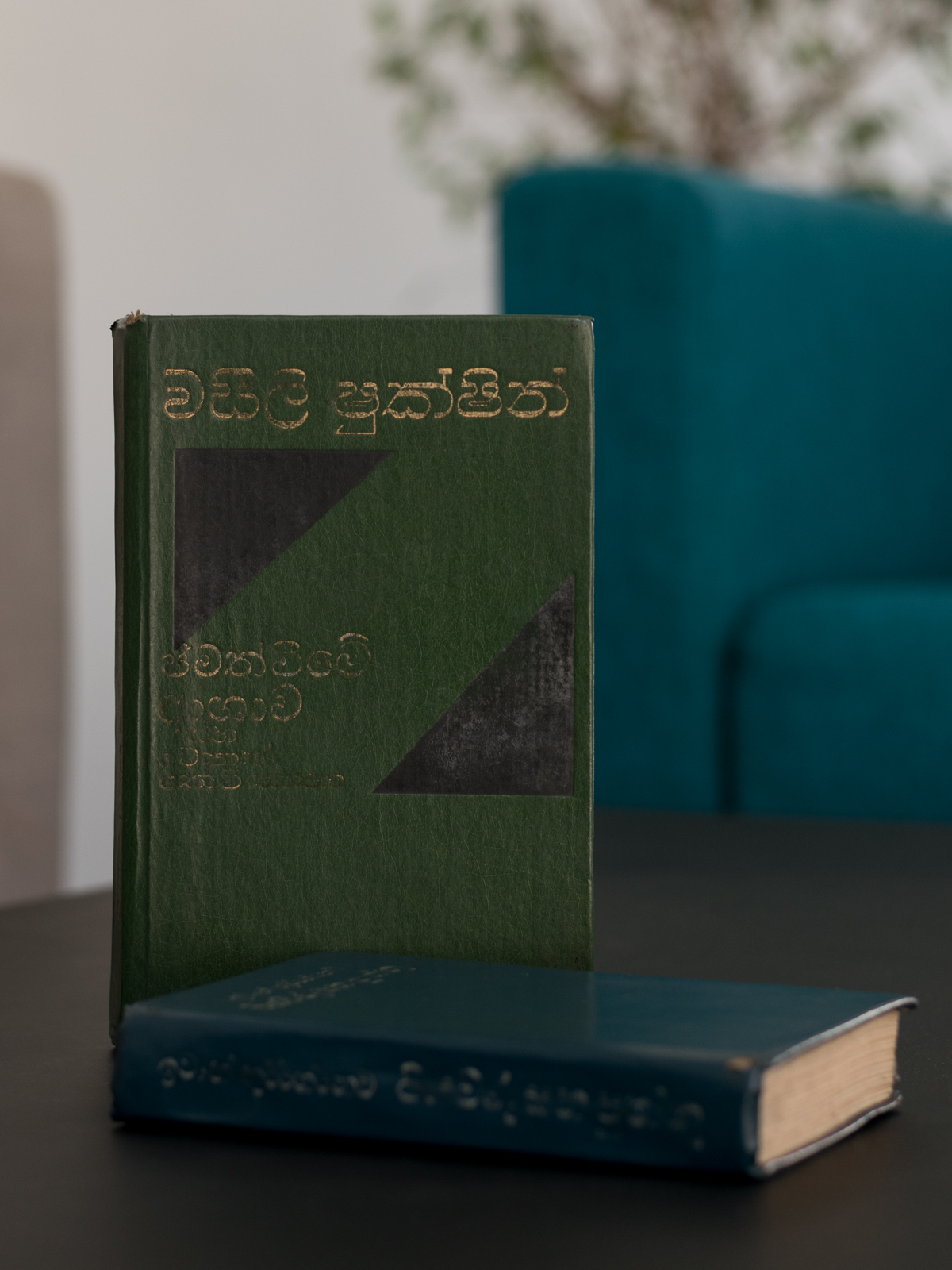

Vincent Rodrigo was also one of that batch of students at Lumumba and was also engaged in translating Russian works. He would go on to be the author with the most Russian-to-Sinhala translations with over 200 in a 25-year career. Many of which were immensely popular in Sri Lanka. Including “Mother” by Gorky and “The First Teacher” by Chingiz Aitmatov. He also joined the then-new Sinhala section of Moscow Radio and was even involved in dubbing Russian films to Sinhala, and was known as the unofficial Sri Lankan ambassador to Russia. Other such notable writers include Oruwala Bandu, H. Jayarathne, Rupasiri Perera, and many others that carry the torch to this day. Many have also received recognition for furthering literary relations between Sri Lanka and Russia.

There were several publishers both here in Sri Lanka and in the Soviet Union that were eager to take hold of this emerging new market. For example, Moscow’s Mezhdunaródnaya Kniga (International Book Establishment). A company dedicated to the worldwide distribution and export of books. In the Soviet era, Mezhdunaródnaya Kniga associated with hundreds of publishers and export huge amounts of literature as well as other intellectual and cultural information materials. As well as Raduga Publishers, a state-owned publication house of the Soviet Union, Progress Publishers and Malish Publishing, which mainly concerned itself with children’s books. In Sri Lanka, the publisher People’s Publishing House made connections with them. Through these connections, Sinhala and Tamil translations of Russian literature were shipped to Sri Lanka after being translated and printed in Russia itself. The first of which was reportedly a children’s book called “Two Stories” published by Mezhdunaródnaya Kniga in August of 1957.

In Sri Lanka

Karunatillake mentions that Gunasena Withana is one of the founders of the Peoples Writers Front (PWF). The PWF was created for the aim of furthering Sri Lankan literature but it also was a key group in fostering the relationship between Sri Lankan and Russian Literary circles. Withana was a guest at events like the 60th-anniversary celebrations of the October Revolution and the golden jubilee of the Union of Soviet Writers. Sirimanna Karunatillake adds, in Sri Lanka, they were very proactive in attempting to tell the public about Russian Literature. They organised many events around the country. On November 12, 1965, on the 75th anniversary of Anton Chekhov’s visit to Sri Lanka, they organised a large seminar at the University of Colombo. For Tolstoy’s 150th birth anniversary on September 9th 1978, the PWF formed a national committee for a truly large scale celebration. The committee counted literary heavyweights like Prof. A.V. Suraweera, Prof. Tissa Kariyawasam, K. Jayatilleke, Munidasa Senarath Yapa, K.G. Karunatillake, Ven. K. Ananda, Gunasena Withana and pioneers of introducing Russian authors to Sri Lanka; Charles Justin Wijewardena and Cyril C. Perera. With their guidance, Tolstoy’s books, photographs, handwriting, discussions of his life and work, conferences, fairs were held throughout the island in September of 1978.

These efforts were supplemented by efforts from the Peoples Publishing House (PPH) as well. PPH acted as the local distributor for all the books that came from the Russian publishers and distributed them islandwide. Using events like the commemoration of the October Revolution, Lenin’s birth anniversary, PPH would organise grand book exhibitions and sales in Colombo and other major cities. They even used mobile book fairs to reach more rural areas. This system worked well and lasted until the fall of the Soviet Union when the supply of books from Russia halted. But their efforts succeeded and Russian literature was firmly embedded in the Sri Lankan literary landscape.

As mentioned before, even today, decades after the active propagation of Russian literature, the genre still enjoys a great love in the hearts of Sri Lanka’s literary public. In the foreword to the reprint of ‘Russian Short Stories’ by Ediriweera Sarachchandra and A.P. Gunarathne, author K. Jayatilleka says, “The Sinhala novel and short story began in its present form from its association with English Literature. But it lit upon the correct path and proceeded to develop further with the influence of Russian and French literature.” But beyond influencing Sri Lankan authors, the original Russian classics are still best sellers across the island in their translated forms, loved by young and old alike. And while they have not received the fame of the classics, newer Russian and Soviet novels still get translated into Sinhala. For example, in September of 2017, Russian-Uzbek writer Hamid Ismailov was hosted at the Russian Center in Colombo at the launch of the Sinhala translation of his book ‘Dead Lake’ translated by Chulananda Samaranayake. The Russian Literary Circle in Sri Lanka is still very much active and conducts its own events celebrating Russian literature like last years Annual Literary festival which was dedicated to the 200th birth anniversary of Turgenev, 150th anniversary of Gorky and the 100th anniversary of Solzhenitsyn. Russian literature is a significant part of Sri Lanka’s literary traditions and seems like it will always be so.

Special thanks to the Russian Center in Colombo and Mr Sirimanna Karunatillake.

.JPG?w=600)