“New York is the new model for the concentration camp where the camp has been built by the inmates themselves and the inmates are the guards, and they have this pride in this thing they have built. They’ve built their own prison. And so they exist in a state of schizophrenia where they are both guards and prisoners. And as a result, they no longer have – having been lobotomized – the capacity to leave the prison that they’ve made or to even see it as a prison.” – Andre, My Dinner with Andre (1981)

For most of us living, and even reading this post, the civil war in Sri Lanka took up a major chunk of our lives. Everyone living in this country was affected by it in one way or another and most of us, I’m sure, feel like we have our own opinion about it. Now that the war is over I’ve, unfortunately, found that the art scene in Sri Lanka has remained extremely static in its ability to frame it and it seems like they’ve unanimously agreed to enter a conspiracy to portray only the pain involved in war. I do not mean to demean the loss, grief, agony, inertia, or the many untold permutations of the effects of war, but, remaining stagnant when it comes to an issue as universal as war does not help to move the conversation forward or find peace and reconciliation.

Image courtesy writer

Image courtesy writer

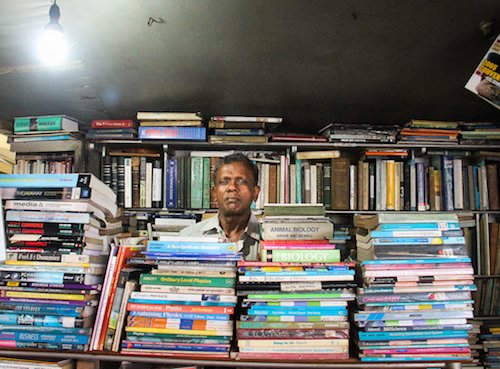

Without returning to the old metaphors and symbols that have been exhausted by most artists, Chandraguptha Thenuwara has broken away from the paradigm and has presented to us a new point of view with his show ‘Glitch’, at Saskia Fernando Gallery. ‘Glitch’ is part of Thenuwara’s annual exhibition and on-going conversation about the civil war in Sri Lanka, in which he goes beyond simply recollecting the chronological events which precipitated.

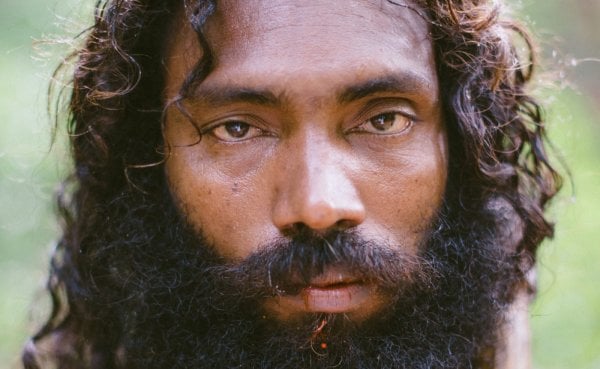

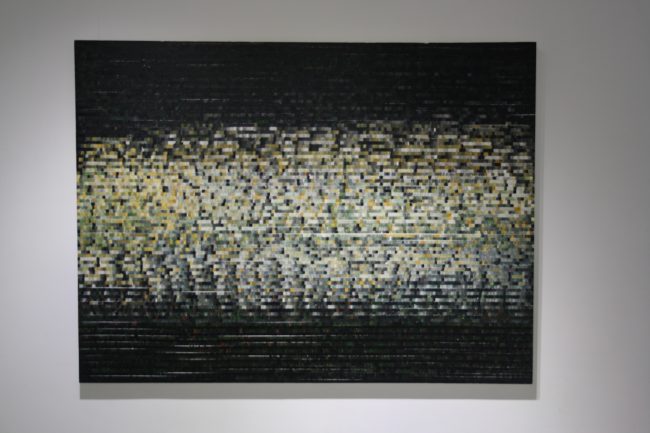

Over the years, camouflage has been a recurring motif in his works, especially at the turning point in his career where he coined the terms ‘Barrelism’ and ‘Barrelscape’. This year he has tackled narratives of how the war is portrayed in media, whether it is via photographs of people who went missing during the war, documentaries, films, or even the countless stories one hears of people’s experiences; once again, camouflage is featured heavily and Thenuwara has given it a new dimension.

Image courtesy writer

Image courtesy writer

Landscape II and Missing Person were, in my opinion, two of the most impressive pieces. The gradation of sanguinary red to murky blues in Landscape II and the silhouette of lost woman floating within shades of harsh oranges laid an ominous foundation to this collection. The way he paints with stark, contrasting images in between each other, almost like a lenticular screen, even if it’s merely the canvas, shows that truths, half-truths, and false information – like a glitch – can be laid together, side by side to control, steer, and, if need be, even suppress narratives. This collection of paintings, with its undertone of anti-propaganda propaganda has made me question if I am a prisoner or a guard of the institution of “facts” about the war that I have grown up knowing about.The paintings are visually stimulating, hard to confront, and also beckon more questions than answers.

Image courtesy writer

Image courtesy writer

Thenuwara, as much as he is an artist, is also a political activist. His work, mixed in with his ideology, is a sublimated, aesthetically pleasing voice of dissension, and is continuing to fill a vacuum that Sri Lanka has felt for a very long time.

This collection will be on display at the Saskia Fernando gallery until August 20.

.JPG?w=600)