“What intrigued me, and something that continues to haunt my films is the idea of people from the outskirts pouring into the city. In our country, particularly at that time the ’60s and ’70s, Colombo was beginning to form, develop an identity. This identity was given shape by those who were moving in from outside… The overall story is the romantic yearning of the youth to belong within the cityscape.”

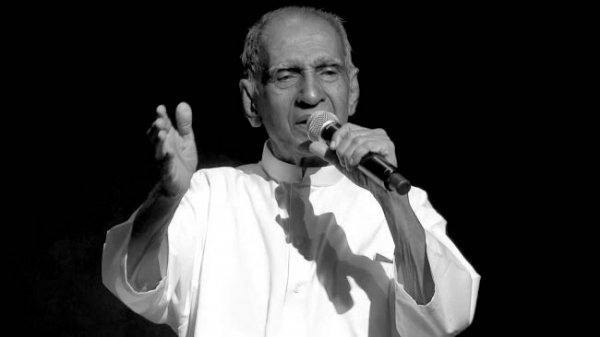

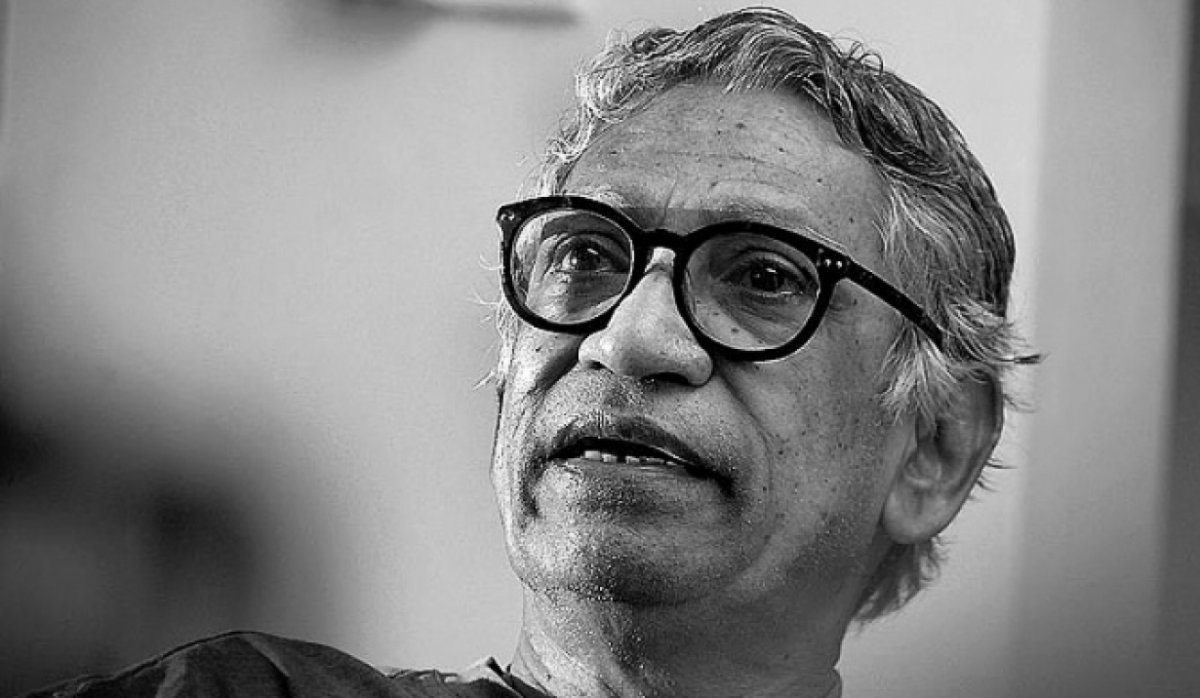

Sri Lankan cinema’s first revolution happened with the coming of the great Lester James Peiris. His movies approached realism rather than the staged movies based on Indian cinema that were popular at the time. In the two decades since Peiris’ debut, Sri Lankan cinema followed his lead but—apart from an occasional outlier— focused on largely apolitical and dramatic themes. Dharmasena Pathiraja and his contemporaries changed that in the 1970s by creating films that had a very socio-political message. So much that they were called the Sri Lankan Rive Gauche.

Rive Gauche comes from The French New Wave. It was a cinematic movement in the 1950s and 1960s where new filmmakers rejected established conventions and experimented with new editing, styles and narratives that focused more on the socio-political issues of the day. A subgroup from them were known as The Left Bank or Rive Gauche. Their work leaned towards the political left and looked at cinema as an art form, as sophisticated as any other. A decade later, in Sri Lanka, this label was applied to Dharmasena Pathiraja; as a titan of Sri Lankan cinema’s Left Bank and a pioneer of Sri Lankan cinema’s Second Revolution. When Sri Lankan youth were engaged in an insurrection in 1971, it was Pathiraja that gave screen time to their issues in that same decade.

A League Of Sky

Pathiraja’s cinematic career begins with Ahas Gauwa (A League of Sky) in 1974. Where films of the earlier decades were of a more patriotic or family focused, Ahas Gauwa took a completely different theme. It focuses on young men that have to face the realities of adulthood as they are confronted with issues like unemployment in the city with only the experiences of a carefree youth. Shown slightly but sharply, the characters were played by future film stars Wijaya Kumaratunga, Swarna Mallawarachchi, Amarasiri Kalansooriya, Wimal Kumara de Costa, Wickrama Bogoda, Malini Fonseka in a movie that showed the struggles of class, youth and employment like never before. Actor Amarasiri Kalansooriya said that Ahas Gauwa was more-or-less his life story. “At that time I was an orphan. Pathi knew that I didn’t even have a bite to eat. He would take me to the Peradeniya University and feed me. Like me,Vijaya Kumaratunga, Wimal Kumara de Costa,we who met on the set of Ahas Gauwa, were unemployed youth then. Pathi told my story through Ahas Gauwa.” says Kalansooriya.

Speaking to Roar Sinhala last year, director Prasanna Withanage said “Sri Lanka gained independence in 1948. But when we gained independence, the dreams we had as a Sri Lankan nation broke down. By 1971, even an insurrection developed from the unemployment and economic difficulties. The first film to portray this dream breaking is Ahas Gauwa.”

Ponmani

Filmmaking was not Pathiraja’s chief occupation. He was a lecturer at several universities for many years. Including the University of Jaffna. Which is when he made Ponmani. The first and only Tamil language film by a Sinhala director. Pathiraja felt that Ponmani was a herald of the era of violence in the 1970s that took over the society of Jaffna. He adds that Ponmani is about women, family and caste. It is also a prescient foretelling of what could happen to the Jaffna middle-class economy in times to come.

“I began ‘Ponmani’ when I was a lecturer at the University of Jaffna during the latter half of the 1970s. Back then I didn’t feel a great difference between ‘Sinhala cinema’ and ‘Tamil Cinema.’ I didn’t feel like I had gone to a different country and was living with a different race. Another thing is that because I’m used to hearing that language, and I got to know these people from a young age, it didn’t feel strange… Ponmani was born because the artists and the people with the artists, from both inside and outside the university, joined with me and shared our experience as one, with the need to do this as ‘our’ thing and the resolve and dedication to do it,” Pathiraja said.

The Wasps Are Here

1977 was the premiere of Bambaru Awith (The Wasps are Here). A story of a small fishing peaceful fishing village. Anton is the fish seller of the village. Making a small but good business out of buying and selling the catch of the day. Cyril and Helen are simple fisher-folk and are engaged to be married. This ecosystem is disturbed by the entry of outsider Victor, who attempts to take over the fishing business with his people. They use motor-boats and modern fishing equipment, and bring with them liquor, cigarettes and guns.

This film was a commentary on the society emerging after the adoption of the new ‘Open Economy’.In a way, it was a foretelling of the coming of capitalist characters like Victor. The peace and fragile societal balance of this remote village was disturbed by this new way of life that was foreign to them. A disturbance that ultimately resulted in the establishment of a police post and it’s looming presence over the village. Pathiraja showed how things may devolve in this new society through his film. It’s often considered as commentary on how people of the proletariat embrace capitalism without completely understanding it’s consequences and the results of that embrace.

Along The Road

Pathiraja’s focus on realistically portraying the problems of the young didn’t diminish with time. 1980’s Paara Dige (Along the Road) was another in that vein that was unfortunately not well received during its initial theatrical run. But is now recognised as one of the best films out of Sri Lanka. The story moves with Chandare and his girlfriend. Chandare is a migrant from the village to the city and he makes his money by exploiting people who have failed to pay the mortgage on their cars. His girlfriend, who ekes a living as a stenographer, lives with him in a boarding house. She becomes pregnant and they decide to have an abortion. But they do not have the 3,000 Rupees that the doctor asks for, and they frantically search for a way to earn the money.

This film is unique in that it takes a theme, or even a trope, that relates to family, such as abortion and takes it’s path of resolution outside the family unit to the everyday men and women. People like the city’s unemployed to the hostels of workers migrating from the villages to the city. It is as much a film about displacement as it is about the two main characters. Using the subject of abortion to penetrate the traditions of the village and city the film shows a picture of the rootless-ness and alienation of the people who come from the villages to the city. It’s an example of the displacement of youth, who are always on the run and looking for something in life but are unable to resolve their problems.

Pathiraja has said that he believes the audience was looking for hidden meanings based on preconceived notions instead of accepting the film’s very simple message. “It is about how everybody is dislocated in the city, the village or wherever they live in this country. It is social dislocation tied up with personal dislocation.”

The body of work that was created by Dharmasena Pathiraja is a humane window into issues that are often overlooked. Not only through films, but with his plays, documentaries and television series as well. His work provided inspiration for a new generation of filmmakers like Prasanna Withanage, Kesavarajan Navaratnam, Malaka Devapriya and others. If it is a more “real” portrayal of Sri Lanka that you are searching for, you could do no better than Dharmasena Pathiraja.