“When I applied to join the Navy, I was twenty years old and had no thought or intention of dying for my country.”

– A Long Watch, Page 4

“The best hope I would have for a book like this – and not just mine, anyone’s – is that it spurs people to tell more. And that gradually, over the years to come, we hear more and more.”

– Sunila Galappatti, speaking at a session at the Galle Literary Festival 2017

On September 18, 1994, the Sagarawardene set out from Colombo. The commander of the ship was Commodore Ajith Boyagoda. Following the voyage, he was due to be posted home to Colombo. But the journey home would take much longer than he could foresee. On September 19, the ship was attacked by the LTTE and Boyagoda was condemned to spend the next eight years as a captive. It would be another 14 years before an account of his experiences would be published. A Long Watch is the resulting story. Like the narrator’s captivity, the book, too, has had a long journey.

The book is billed as by ‘Commodore Ajith Boyagoda as told to Sunila Galappatti’. The book starts with Boyagoda joining the Navy as a young man (when Galappatti first showed the manuscript to him, he is reported to have asked “Do we have to start at the beginning?”). It is indeed the very beginning, so much so that at first the reader wonders ‘where is the drama’? The first half of the book is an account of his life as a Naval officer. His capture by the LTTE occurs midway in the book; the rest is an account of the eight years of his captivity.

Sunila Galappatti, author of A Long Watch. Image courtesy galleliteraryfestival.com

Telling someone else’s story can be complicated. How much of it is the narrator’s voice? How do the author’s own subjectivities play out? To what extent is it a conversation, and to what extent is it an intervention in the writing? These are some of the questions that Galappatti tackled at a session at the 2017 Galle Literary Festival, moderated by Ruhanie Perera. She recounts asking Boyagoda whether telling the story to a civilian woman would influence the way the story was told. Would he have told his story differently to a naval colleague? His response, she says, was an emphatic “I always tell this story the same way.”

“But—” she added, “I would say that while the billing on the book says ‘Commodore Ajith Boyagoda as told to Sunila Galappatti’ it’s more ‘as heard by me’. Inevitably, in structuring the narrative, I have chosen what is in and what is not.” She notes another interesting point “…if I allowed myself into the narrative, there would have been no stopping it. I tried as much as possible to tell the story he told. That was the discipline I tried to maintain.”

This discipline—the ‘keeping herself out of the narrative’—makes the book work. There is a very strong sense of it being Boyagoda’s voice, as if he talks directly to the reader. And there is a sense of a person—stoic, unemotional, measured.

The tone of the book is unemotional—it is a book about a dramatic subject related with a remarkable absence of melodrama. But the end effect is very moving. The impact of the book builds up gradually through quiet, matter-of-fact statements. In spite of the lack of obvious emotion in the tone, there is a full realisation of what has been lost through the years of captivity.

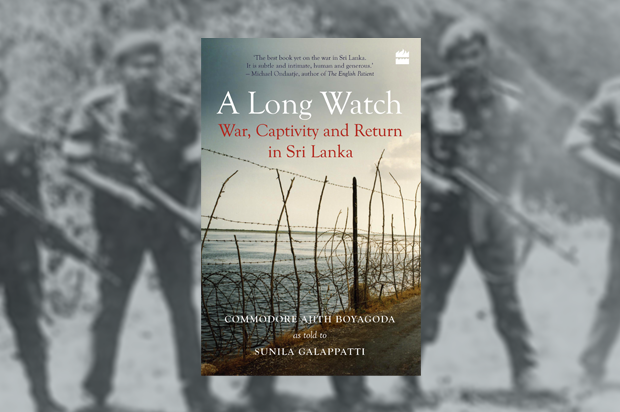

In spite of its dramatic subject, A Long Watch is a nuanced account of a war story. Image courtesy indianexpress.com

A Long Watch could have been a straightforward story of capture, a difficult captivity, and a triumphant release. It is a much more nuanced, complicated account. Describing the moment when he was pulled from the sea, Boyagoda says on page 66 of the book, “I knew they were my enemy. But at the time it felt like a rescue”. His treatment by the LTTE was, he says, good. “I was a prisoner of war,” he says in the prologue to the book, “and the treatment I received was as good as I could have expected in the circumstances”. But as a high-ranking officer, he was to a certain extent a ‘show’ prisoner. He acknowledges, “I know mine is not the only story. I have heard screams coming from underground cells. But this is my story, such as it is.” And though he says he was treated well, this a relative term. There were times when it was a hard ordeal.

There is perhaps temptation on the part of a reader to make every book on the war the definitive account of the war. Galappatti cautions, “this is by no means a treatise on how I feel about our history. Far from it. And it’s one man’s story from among hundreds of thousands that we will not hear as well.”

But the fact that it is one man’s story is precisely what makes it valuable. There has been much analysis written on the conflict, but less observation. Boyagoda was in the power of his captors, but he was also an observer of their behaviour. And it is this that makes the book interesting.

At the beginning of his captivity, he is taken to hospital. He recalls:

“There were also Tiger cadres who came to see us purely out of another curiosity. They had never seen these Sinhala people they were fighting.”

Over the years, he builds up friendships with some of his captors. Of one of them, ‘Mohan’, he says:

“…Mohan seemed to enjoy recounting stories of his childhood in the South. He had started his life in Wellawatte in Colombo, and gone to school at Royal College. His family had been displaced to Jaffna after the 1983 riots. Eventually, the rest of Mohan’s family had migrated to Switzerland while he joined the movement. I imagine that it was Mohan joining the movement that had been his family’s pass to leave—the LTTE sometimes extracted these bargains. But it was also something he had chosen, he said… He told me that his mother despaired of his choice. She told him that he was trying to win freedom for his people by losing his own.”

While there is a genuine regard for individuals, there is also a clear recognition of the LTTE’s weaknesses. On page 185, when he is finally released, he says:

“I think this was also why the cadres we had known were sad to see us go… It must have been hard to watch us being freed, while they remained, essentially, in captivity… A lot of these cadres, even the ones who joined the LTTE voluntarily, joined as teenagers. That is when the mind is more open to militancy. But eventually you want more of life than a singular cause.

“But here we were, seven prisoners leaving for better lives than our captors could hope for. The bus came. We got in, waved good bye, and started the journey back.”

A Long Watch is sad in an unexpected way, partly because there is no easy, happy ending. Boyagoda is released but the transition back to a ‘normal’ life takes time. This is Boyagoda, on page 199:

“When you’re in the world you adjust to changes as they come. They become part of you. But I felt I had dropped from the jungle into a new reality… My children were growing up in a world I did not know well enough for me to be any sort of guide to them…I was worried that I would mess things up even if I tried to just to help with their homework. I didn’t know my children well enough to know how to suggest things to them.”

Commodore Ajith Boyagoda was held captive by the LTTE for eight years. Image courtesy dailynews.lk

The other moving part of the book is the reminder of the many untold stories of others caught up in the war: the lives that intersect briefly with Boyagoda’s account. On page 217, Boyagoda says:

“At the end of the war, I was relieved the war itself was over. At least the part of the conflict that was an outright war had come to an end. I had to be relieved about that. I could stop fearing that someone I knew would be blown up on a bus in Colombo. That was some consolation—I didn’t want to forget that…But I was aware of so many lives that had been lost or ruined—people I knew and thousands more I did not know. There is absolutely no victory in a war—I’m sure of that.”

There are many such lives on both sides of the conflict: the executive officer who told Boyagaoda on the night the ship was sunk, “Sir, apita gehuwa” and who is listed as missing in action to this day; the seaman who clung onto the raft next to Boyagoda, whose bullet-covered body was recovered later. And from the other side, the young children of his captor who came to wave goodbye on the day when they were finally released, and Mohan the young boy from Wellawatte. Later, he wonders what became of them. So many untold stories, so many lives that came apart because of the war.

A Long Watch deserves a wide readership. Because there is immense value in one man’s story. Because there are so many stories that will likely remain untold. And above all, because one day it may lead to more of those stories being told.

Note: The quotes from Sunila Galappatti are taken from the session ‘In conversation: Sunila Galappatti on a Long Watch: War, Captivity and return in Sri Lanka’ held as part of the Galle Literary Festival on January 13, 2017. The session was moderated by Ruhanie Perera.

Featured image courtesy galleliteraryfestival.com