In a quiet private street in Cinnamon Gardens, Colombo, is a large and spacious old house, enclosed by a sliding metal gate. It is quite an ordinary house for such an upmarket area, only a short walking distance from the town hall. It’s not until you enter that you find yourself somewhere quite extraordinary—the home and private office of Sir Arthur C. Clarke, which has been left relatively untouched since his death nearly ten years ago.

The entrance to Sir Arthur C. Clarke’s residence. Image credit: Roar/Michael Gregson

Sir Arthur would have been 100 this year. He may be gone, but his star shows no sign of fading, with his literary and movie legacy still lingering on. The script for the award-winning 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, which Clarke co-wrote with director Stanley Kubrick, was based on his short story The Sentinel and is one of his finest works to date. More recently, his novel Childhood’s End was adapted into a television series in the United States, winning a new generation of fans.

But here in Sri Lanka, there are doubts about whether the office he called his “ego chamber” can remain open for much longer.

It is a fascinating place, if slightly eerie, giving you the uncanny impression that the ghost of the Sci-Fi master still lingers. Once you enter, you find yourself in a vestibule wallpapered with a giant image of the Earth as seen from the surface of the moon. Apart from a little peeling, you could almost picture it as a backdrop on the set of a science fiction movie.

When you go up the stairs to the first floor, you come to an outer office, where the writer’s staff used to carry out research for his new books and TV shows, like Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World. Among those who worked here was Sir Arthur’s former colleague, Nalaka Gunawardene. Gunawardene first started working there in 1987 as a research assistant for non-fiction books. He also handled media relations. By the time of Clarke’s death in March 2008, he had become firm friends with the author. “He was a fascinating, multi-faceted personality,” Gunawardene recalls, “He took his work very seriously, but he didn’t take himself seriously. He was a very easy-going, jovial kind of person, and every day I learnt something fascinating by working with him.”

He recollects how Sir Arthur used to love Sri Lanka, but stayed true to his British roots. “He [Clarke] settled down in Ceylon, which then became Sri Lanka, for 51 years, from 1956 onwards,” Gunawardene says, “But in some ways, he remained an Englishman. He didn’t really warm up to our rice and curry. He used to have a more English kind of diet. But in other ways, he became completely Sri Lankanised, like he was fond of the sarong. He even wore the sarong when he was part of a Sri Lankan delegation to the United Nations disarmament talks in the 1980s. When the rest of the delegation was in full suit, European dress, he turned up wearing a white sarong and shirt—the national dress. He was a universal man who lived in Sri Lanka, was proud of his origins as a farm boy in rural England, and was a citizen of the world.”

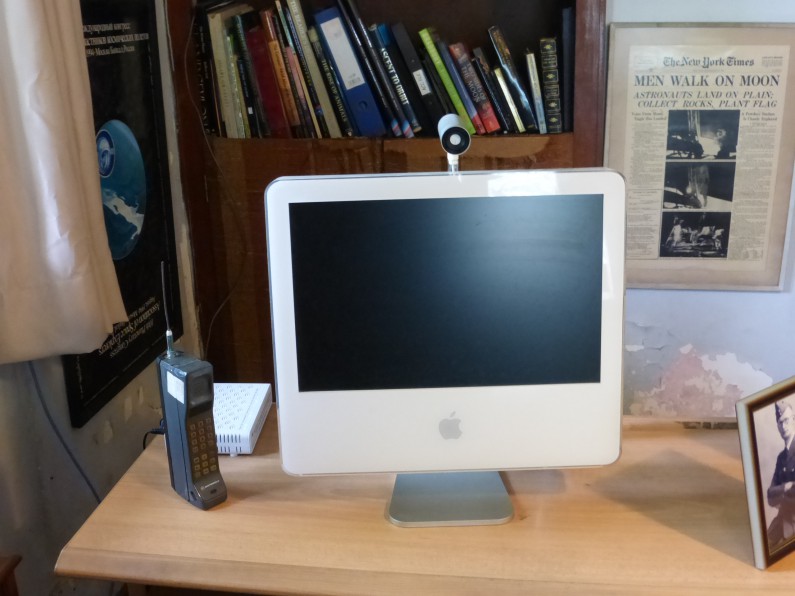

Sir Arthur’s computer and cellular phone. Image credit: Roar/Michael Gregson

In Sir Arthur’s office, an old Mac desktop computer still stands on his desk next to the equally old cellular telephone he used to communicate with staff in distant corners of the house. The author’s wheelchair sits to one side of the desk. He was struck down with the muscle-wasting post-polio syndrome in 1984. Although he had difficulty getting around on solid ground, Sir Arthur never lost his love for scuba diving—the reason that had first brought him to Sri Lanka so many years ago. Deep under the ocean, he could move about nimbly till his 80s. He loved the sensation of floating free in the water.

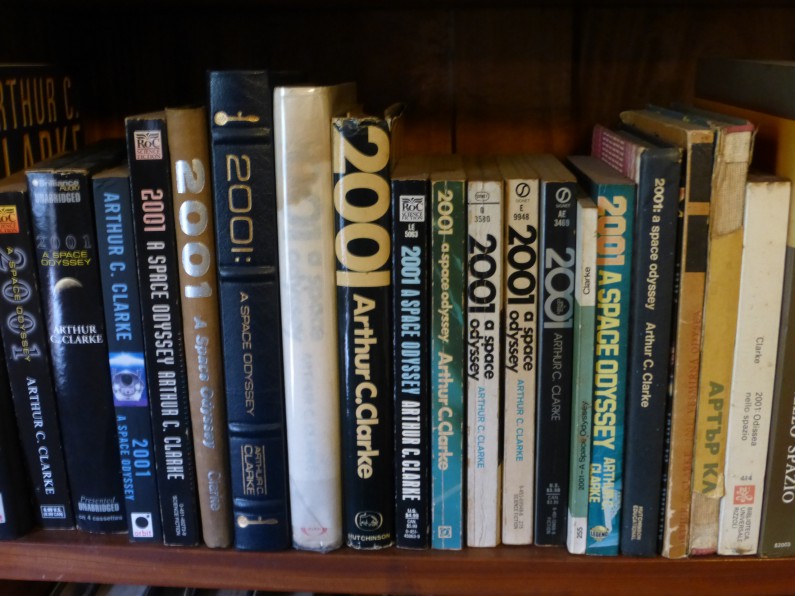

Framed pictures and other knick-knacks cover almost every inch of wall and shelf space, telling the story of Sir Arthur’s life. Among the mementos is a framed front page of the New York Times from 1969, announcing “MEN WALK ON MOON.” One whole bookshelf is given over to translations and various editions of Clarke’s most famous work, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

A shelf with various editions of Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Image credit: Roar/Michael Gregson

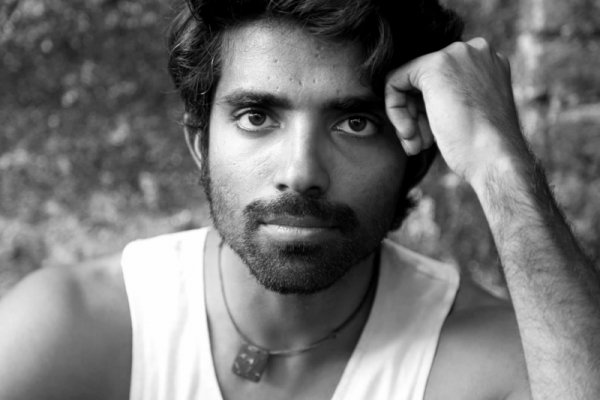

On other shelves stand an intriguing array of souvenirs, including a scale model of a Soviet rocket. A large black and white framed photograph of a handsome young man hangs on one wall. It belongs to Leslie Ekanayake, a close friend of Clarke’s, who died in a motorbike crash in 1977, aged 29. Sir Arthur dedicated his 1979 book, The Fountains of Paradise to Ekanayake, writing:

“To the still unfading memory of LESLIE EKANAYAKE (13 JuIy 1947—4 July 1977). Only perfect friend of a lifetime, in whom were uniquely combined Loyalty, Intelligence and Compassion. When your radiant and loving spirit vanished from this world, the light went out of many lives.”

A framed photograph of Leslie Ekanayake. Image credit: Roar/Michael Gregson

Sir Arthur was long rumoured to be gay. When asked about his sexuality, he used to describe himself as being “mildly cheerful”. But to those who knew him well, his sexual orientation was no secret. He was a private man who preferred discretion and respected his Sri Lankan hosts too much to cause a scandal. Gunwardene says, “As a resident guest living in Sri Lanka on a long-term visa, he was very careful not to get involved in local politics—not to get involved in very heated controversies.”

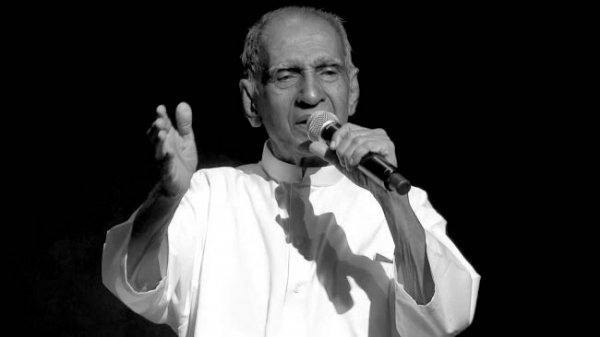

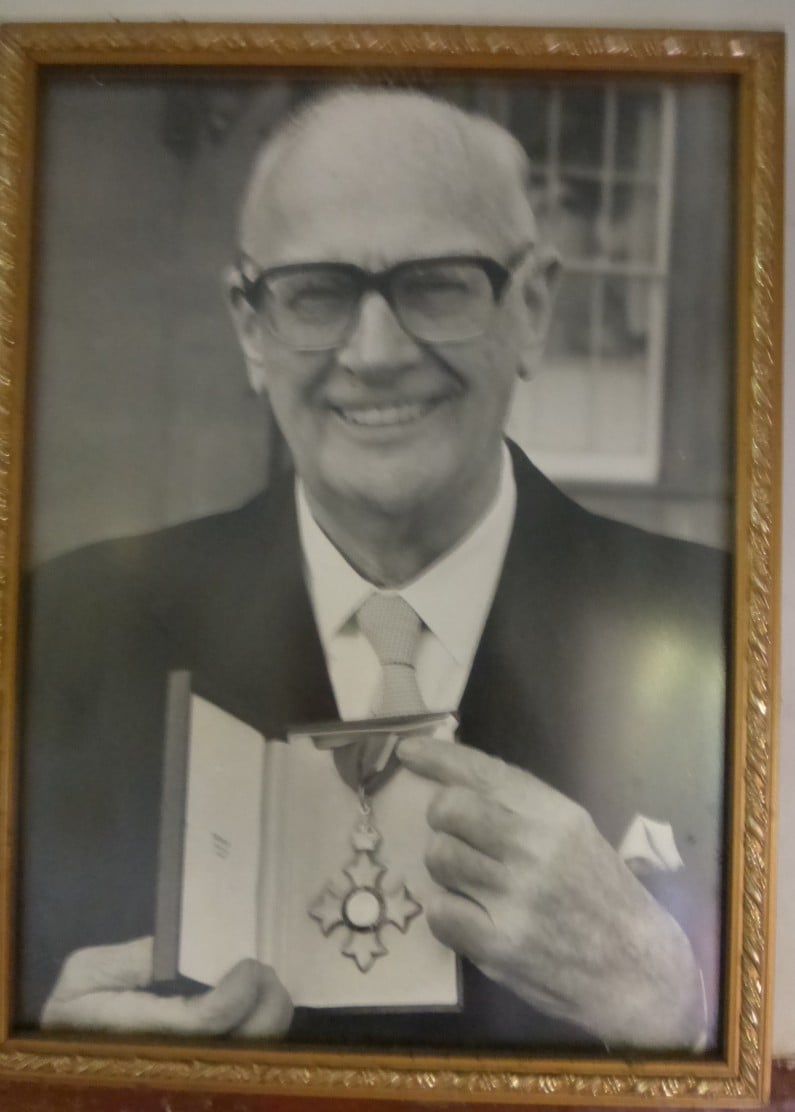

A framed photograph of Clarke. Image credit: Roar/Michael Gregson

So it came as a bolt from the blue when a British newspaper accused Sir Arthur of being a gay paedophile. His friends believe there was an ulterior motive for the tabloid exposé. “It shook him up,” Gunawardene declares, “It was at the time he was about to receive the knighthood from Prince Charles, who was visiting. The news was timed for [the Prince’s] arrival and therefore, [it was believed] that it was done with the aim of embarrassing Prince Charles. When the news broke, Sir Arthur issued a strong statement denying [it] as well as ever having spoken to the reporters involved.”

Though Sir Arthur never sued the British newspaper for libel, he was eventually cleared of any wrongdoing by the Sri Lankan authorities. But to some extent, the allegations stuck and tarnished his memory. No whiff of scandal lingers in Sir Arthur’s “ego chamber”, however, which remains the perfect tribute to the man and his work—and that’s the way Nalaka Gunawardene wants to keep it. He says, “It has changed very little, actually. We don’t have his cheerful presence in the office anymore, but practically everything else is as it was when he was occupying that table and these sofas. So it’s been preserved like a time capsule. It’s deliberate.”

However, the future of this remarkable memorial could be in jeopardy. “In the long term, some arrangement will have to be made, but one thing is very clear to those of us who worked with Arthur in the last few decades of his life—entrusting this facility to any part of the Government of Sri Lanka will not be a good idea,” Gunawardene confides, “There is already a government agency named after him—the Sir Arthur C. Clarke Institute, which hasn’t been productive. It remains a big drain on public funds—basically a white elephant, and a disgrace to the name of the man.”

He adds, “We have a national museum that can’t look after its own artefacts. So there isn’t really any prospect of the Government or the state coming forward [to preserve Clarke’s home]. So it remains to be seen whether this can be preserved in the long term by the Trust, and what the business model will be for its maintenance.”

Everything is just as Clarke left it. Image credit: Roar/Michael Gregson

Editor’s note: A previous version of this article incorrectly referred to Clarke’s cellular device as a walkie-talkie.