The hall seems to throb with the beat of drums and feet. There is neither music nor are there delicate pirouettes or clicking heels. This is traditional Kandyan dancing, with the thunder of stamping feet and the strength of sweeping arms. Yet, there is a grace and fluidity to the movements as well, underlined by deep spirituality. In one corner of the hall, a group of students and their guru sit with their eyes closed in meditation, and at the beginning of each class, dancers plie deeply and touch the ground, as a means of invoking blessings.

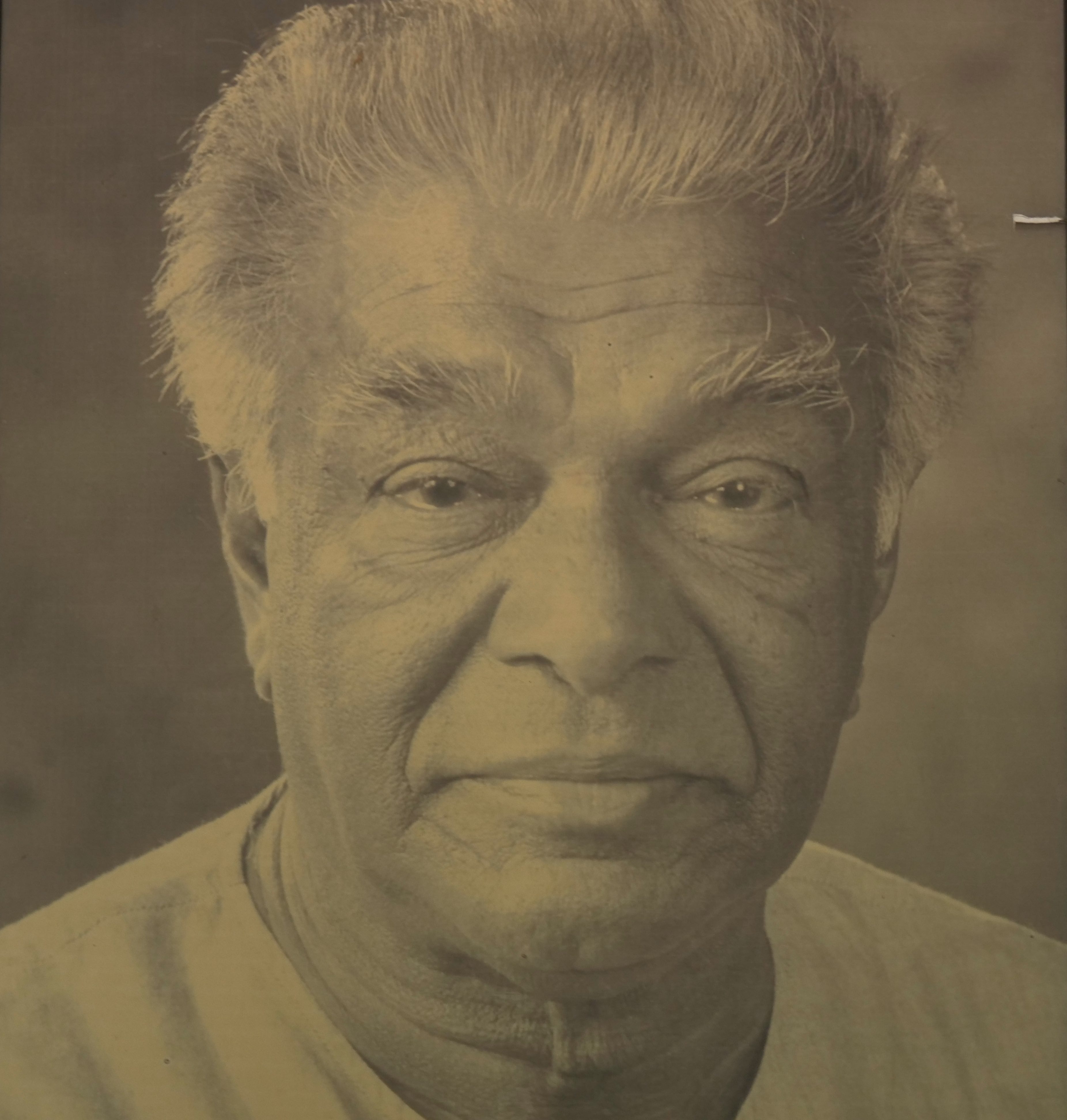

This is the Chitrasena Kalayathanaya, the sacred space in which the heirs of the late dance doyen, Chitrasena, carry on his legacy. “My grandfather started the dance company in 1943, so this year, we will be celebrating 75 years,” says thirty-year-old Thaji Dias. The youngest granddaughter of Chitrasena and Vajira, she is currently the principal dancer of the Chitrasena Dance Company, as well as a teacher in the school. She describes the long, airy hall as a ‘temple of dance’— here, under the watchful gaze of a portrait of Chitrasena, they rehearse for performances, hold workshops and conduct classes. “My grandfather was one of the pioneers of traditional dance in Sri Lanka,” she tells us. “He basically brought it from the ritual to the stage.”

From Folk Ritual To Theatre: How Chitrasena Helped Save Traditional Dance

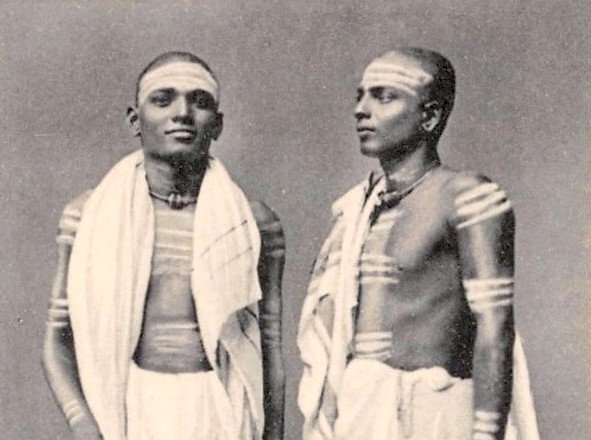

The early 1900s, British Ceylon. With the steady spread of Western concepts, native traditions were on their last legs, and a rigid caste system saw dancers and drummers being looked down upon as inferior. “My grandfather felt that it was important to give these traditional artists a place to continue their art forms, to make [them] seen again and pass them on to the next generation,” Thaji says.

How Chitrasena went about it was unprecedented. He took the dance, which was confined only to rustic ritual grounds, and adapted it for the theatre. This was easier said than done — on the one hand, there were the colonial rulers who disapproved of indigenous arts, while on the other, there were the traditional dancers from the dance paramparas (or families), who thought he was contaminating the art by infusing it with theatre. Even after the establishment of the company and the school, there were numerous obstacles that had to be overcome, including a lack of patronage, poor funding and little or no media coverage. With dogged persistence, however, Chitrasena saw his vision materialise. Now 75 years later, his legacy is flourishing.

Chitrasena understood that it would be nearly impossible to keep the rich indigenous dances alive without adapting them to suit contemporary audiences. “There is one thing which my grandfather used to say, which still keeps ringing in our heads,” smiles Thaji. “The new is only an extension of the old.” It is with this mantra in mind that they continue to create compelling theatre performances by using the elements of traditional dance. “Take choreography for example,” she explains. “My cousin Heshma, who is artistic director of the dance company, always does the choreography by drawing inspiration from our roots. So we continue to do innovations for the stage, but always within the framework of the technique, so we do not harm its essence and beauty.”

The Art And Skill Of Becoming A Dancer

“I love Kandyan dancing. My father was a dancer in Kandy. He used to be a part of the peraheras,” says Deshapriya* (name has been changed). He is sweating profusely after the rigours of the class, but his face lights up when he talks about what dancing means to him. “I do drama on the side as well as dancing here, and ever since I took part in Kumbi Kathawa [a 2015 production], I have wanted to do this professionally.”

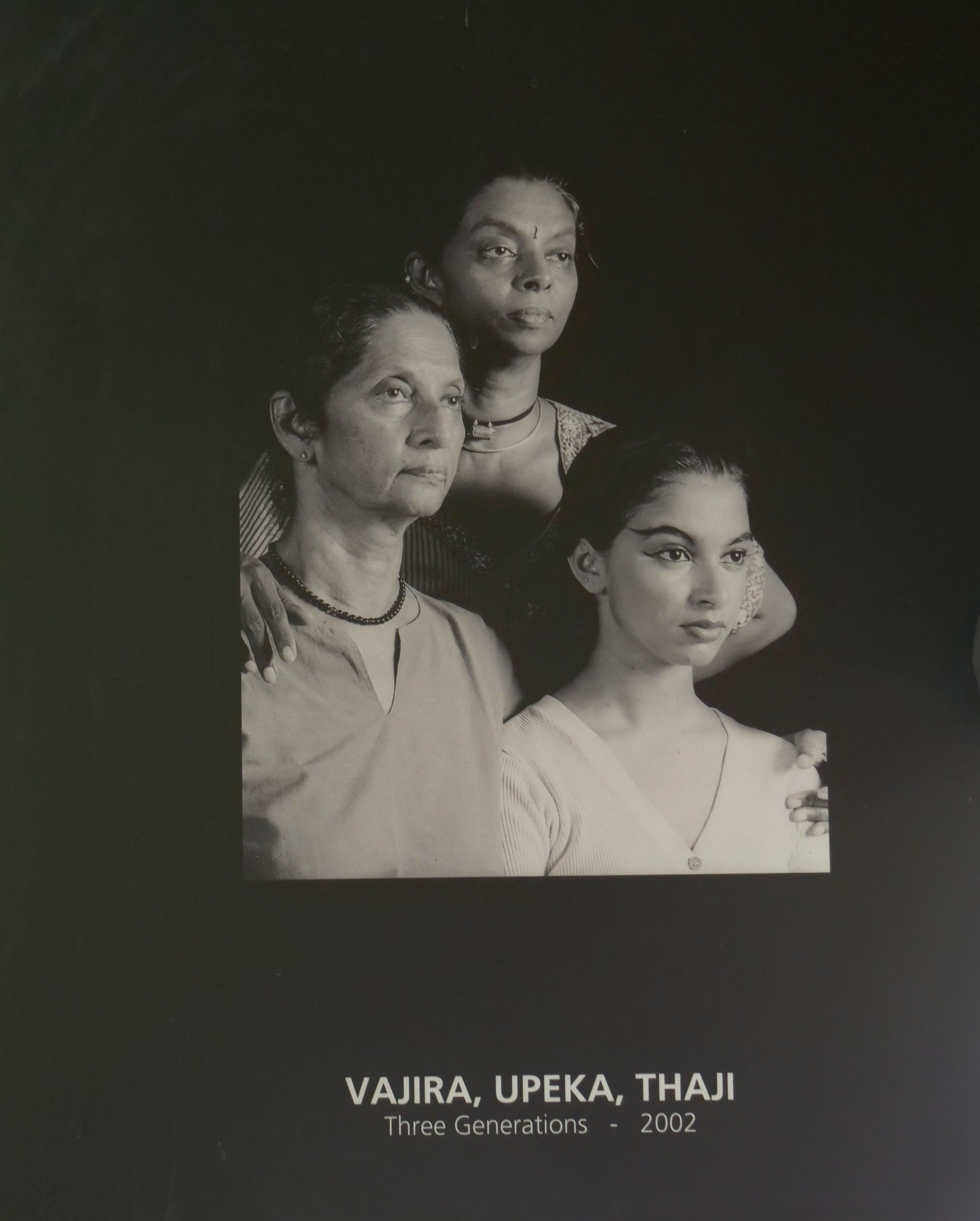

Deshapriya is one of the 350-odd students who come to the Chitrasena School of Dance to learn the intricacies of one of Sri Lanka’s oldest and most popular art forms. The youngest students are about four-and-a-half years old, while the older ones are generally university students. At the helm of it all is Vajira, the late Chitrasena’s wife. At the age of 86, she can no longer dance, but as principal, she is still the driving force behind the school. Sitting under a portrait of her late husband, she oversees the scholarship students, starting off the class with a warm up routine for which she herself beats the drum. At the opposite end of the hall is her daughter Upekha, drum across her lap, overseeing another class. Thaji teaches a set of younger students, as does Anjalika, Chitrasena’s other daughter.

“There is a lot of interest in learning this art form,” says Thaji. “However, not everyone can do it the way we do it here. You see, we live in this time where everyone is looking for quick solutions, but that’s not how we work. We always take the longer route, and our training is rigorous and intense. There are no shortcuts.”

In the school, the students study more than just dancing; drumming is just as important. (“It is almost like there is a marriage between dancer and the drummer,” says Thaji. “You can’t have one without the other), They also learn music, choreography, costuming, production, lighting and everything else they need to know about living as a dancer.

One of the greatest constraints to pursuing dancing full time is finances. “Not everyone comes from well-to-do families,” says Thaji. “There are so many students who love dancing and have amazing talent, but can dancing put food on the table all the time?”

However, most of the older students there seem determined to take up dancing as a career. “Kandyan dancing has a high place in Sri Lanka,” says Deshapriya confidently. “I am sure there won’t be any financial issues. This is what I want to do for the rest of my life.”

In The Shoes Of The Principal Dancer

“If there is a more captivating dancer than Thaji Dias, I have yet to see him, or her.” – The Australian

This was one of the rave reviews the Chitrasena Dance Company received after they performed Dancing for the Gods in Australia. Thaji has lived and breathed dance all her life. She spent her childhood in the dance hall, watching her mother and aunts dance and teach, falling asleep to the sound of drums and jumping in to fill in for absentees in the classes. The turning point of her career, she tells us, came in 2012, when the company collaborated with the celebrated Indian dance ensemble Nrityagram for Samhara, which they even performed in New York. “We lived with the Nrityagram dancers in their dance village for a while. That’s when I realised that I have to do this full time if I want to succeed,” says Thaji. “I want to dance for the rest of my life.”

Slight and supple, Thaji looks like the embodiment of a dancer. “I don’t really have a special diet or anything like that,” she laughs. “The only thing I do to maintain my body is dance.” She reminds us that even though Chitrasena has been succeeded by women, the dance form used to be a predominantly male one – and hence, rigorous enough to help maintain her dancer’s body. “I will probably have to watch my diet as I get older though,” she adds.

Thaji has high hopes for her grandfather’s legacy, and is proud of how far the school has come since its humble beginnings. However, she has not thought far ahead for herself. “Injuries are a dancer’s biggest enemy, so I actually don’t have any long term plans for myself. I just take each day as it comes, because your body could give up at any moment,” she says. She is still amazed at how fully the family is immersed in dance, and tells us that the fourth generation of her family is also being introduced to it now. . “None of us were ever forced to do this,” she smiles. “We all just realised that we love it.”