It is a rainy morning in Jaffna when we set off in a rickety three-wheeler to find 32-year-old Amarasingham Narthanan, a carpenter and woodcarver devoted to creating colourful chariots used in religious processions by Hindu kovils. The road to Araly winds along the coast of Jaffna. Strong gusts of salt-sprayed air whip through the open sides of the taxi as it teeters on its three wheels trying to plough ahead in the face of an impending storm.

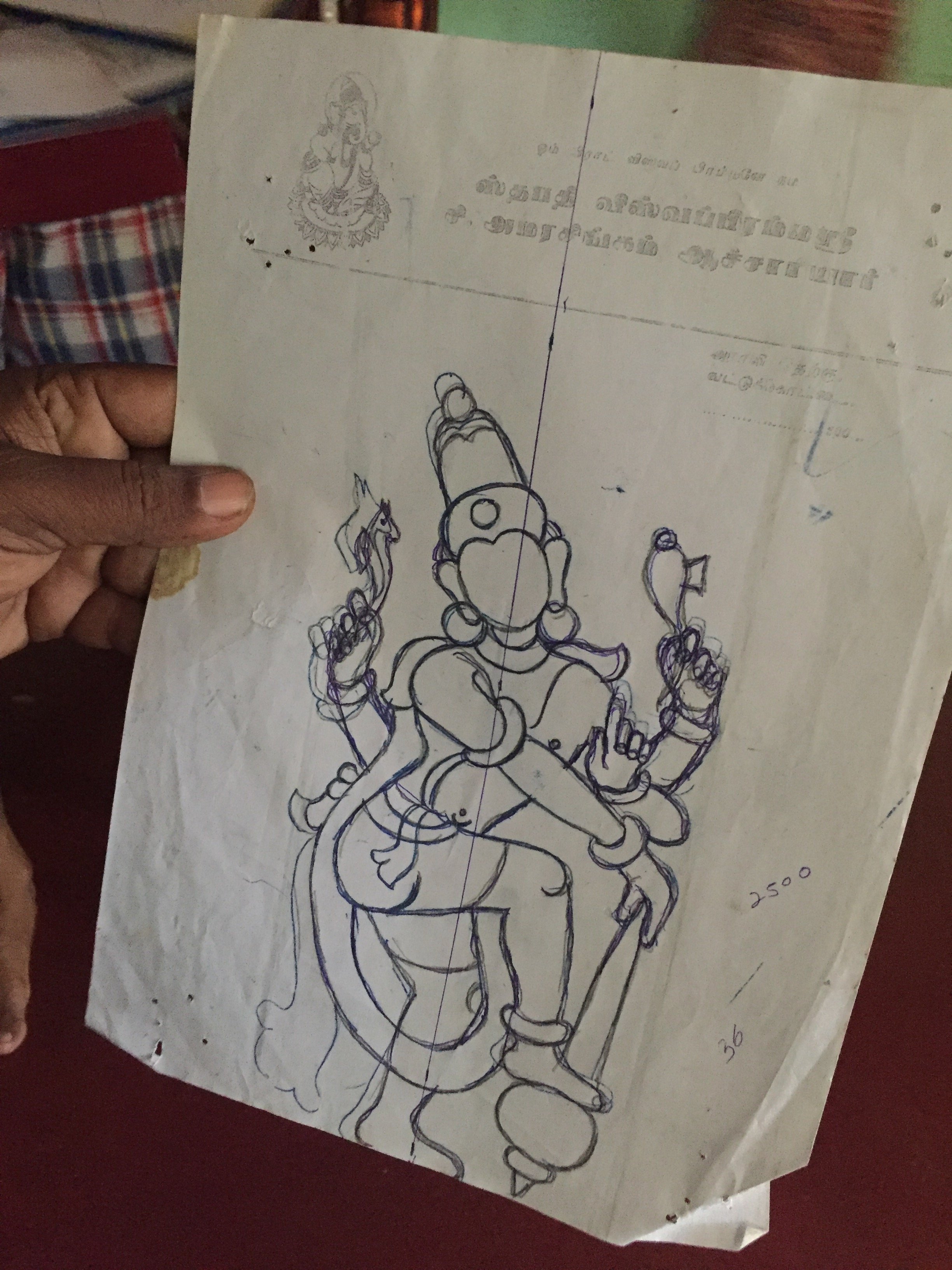

Araly is a small fishing village eight kilometres north of Jaffna town, where many of the ‘asari’ caste of master carpenters also live. The asari have traditionally engaged in carving figurines and chariots for Hindu kovils. Narthanan is a sixth generation carpenter. A slight, fair young man with a betel-stained mouth, Narthanan at first refused to maintain eye contact. But before long, he grew excited and dug through drawers to find dusty cardboard sheets on which he had sketched fantastic figures of birds and beasts, dancing male and female figures and intricate architectural designs for the chariots that he makes with the help of a team of about eight workmen.

For such a quiet man, he is also remarkably resolute in his belief that he is one of the best in the business. “There are many other carpenters in the village,” he said. “But people come to me for my skill and my talent.” Narthanan has only completed three chariots so far. His father, he told us, made as many as 25 before he died in 2015 at the age of 72 – the same year that Narthanan entered the business full-time as a 22-year-old. But three chariots is nothing to scoff at. Chariot-making is a painstakingly intricate task that takes as long as 12 months to complete, and Narthanan is still a fledgeling—albeit very talented— ‘master carpenter’.

Narthanan’s home, where he lives with his ageing mother and young wife, is fairly large, yet sparsely furnished and painted a shade of mint green. High up on one wall is a large picture of his father, Sinnathambi Amarasingham, heavily garlanded in jasmine flowers, with the scent of a joss stick permeating the air.

Next door to his home is a sizeable plot of land, in the middle of which is a wooden shed. This is where Narthanan and his team create the chariots used in Hindu kovil processions. The sound of hammering reaches us as we approach the shed. An elderly man seated on the ground is chiselling a figure out of a wooden block. Not too far from him is a mounted lion – a menacing beast painted orange and red, mouth open to display white incisors. At the back of the shed, an unfinished, headless torso stands dressed in what looks like bygone military regalia, while little blocks of other carved figures lie scattered on the workbenches.

Although time-consuming, chariot-making is a lucrative business. “The total cost for building a chariot is about six million rupees, and I get 2.5 million,” Narthanan said. He said the commissioning kovil raises money for building the chariot from villagers and devotees, especially those from the diaspora. Apart from chariot building, Narthanan also makes the ‘thavil’ and ‘natheswaram’, two musical instruments used by Tamils in the north on festive occasions. He is also retained by a number of kovils to perform periodic maintenance work throughout the year. Narthanan enjoys his work, considering it a fulfilment of his destiny.

But for now, Narthanan is only just establishing himself. He trained and worked briefly as a banker, before his father’s death pushed him into his current line of work. But he has no regrets. He smiles sheepishly, finally making eye contact with us, happy that he been able to share his love for his craft. Pointing to the picture of his father up on the wall, he says, with a shake of his head, almost as if he is unable to believe it — that his father would be very happy too.