Ganesha Vidane has an unusual story to tell – one that began well before she was born, all the way back to the 1920s. She is the daughter of Banda and Dagmar Vidane, who were both circus performers. In fact, her father Banda was born and raised on a circus and went on to become one of the most famous circus performers in the world.

“He was raised on a circus” are words that deserve a black and white movie with gay, classical music playing in the background. For Banda Vidane, however, those words are painted in reality. This is the story of Banda, now in his 80s, who became a world famous elephant trainer and performer in Germany in the late 1900s – but not just any trainer. Banda was known for his special bond with his elephants and even received an award from the Dutch Animal Rights Society in 1988 for his humane treatment of his close friends, the elephants he trained.

It all began one distant day in the 1920s…

The Chance of a Lifetime

For Banda’s father, Epi, it was the chance of a lifetime. At an event hosted for King George V in Ceylon in 1925, Epi performed a trick with an elephant that caught the attention of Mr. Hagenbeck, the owner of one of the greatest Animal Parks (zoos) at the time. Epi’s trick, where the elephant lifted and carried Epi around while his head was in the elephant’s mouth, was an instant success. It marked the beginning of Epi’s career where Epi embarked on a journey that would change his life forever.

Impressed, Mr. Hagenbeck paid Epi to perform his trick in Hamburg at a show called Wonders of South India. Soon, Epi was on his way to Germany by boat, with his elephant as his companion.

Many Years Later…

…in 1937, Premadasa Puncha Vidane, also known as Banda, was born in Frankfurt and raised on a circus. His life was far from ordinary but to Banda this was the only life he knew. He grew up sneaking out on the quiet to visit the elephants in the stables, and this left a lasting impression on him. Epi disapproved of his son’s over-fondness for the animals but Banda was unstoppable. His showmanship showed even at the age of 3 when Epi asked Banda to lie on the floor at the show as part of the trick. Banda was fearless but the elephant, not so. Scared that she might hurt the little boy, the elephant showered him with a jet of urine instead of carrying out the command, much to the amusement of the audience.

Banda was soon part of Epi’s act, making his first appearance in the ring at the age of 5. At 14, he was fully integrated into the act but Banda was a different breed.

While Epi was used to the Sri Lankan mahout technique of training, where the elephants are often punished, Banda was a rebel. To him, each elephant had individual abilities and it was these abilities that he nurtured. While Epi mainly taught his elephants to carry, push and pull things, Banda integrated movements that came naturally to the elephants. Looking back, Banda explains that he trained the elephants according to “their own needs.” Depending on the talents and attention span of each elephant, he trained them and nurtured their strengths and natural abilities like standing on their back legs (they do this to reach for food) and making a headstand (to get roots out of the ground). Banda felt as if he belonged to them – they had their own personalities, fears and talents.

“His method was love and patience,” his daughter, Ganesha, explained. “Whatever the trick, it was something both my father and the elephant were comfortable with. Elephants do, in their own way, communicate when they are not up to doing something,” she said.

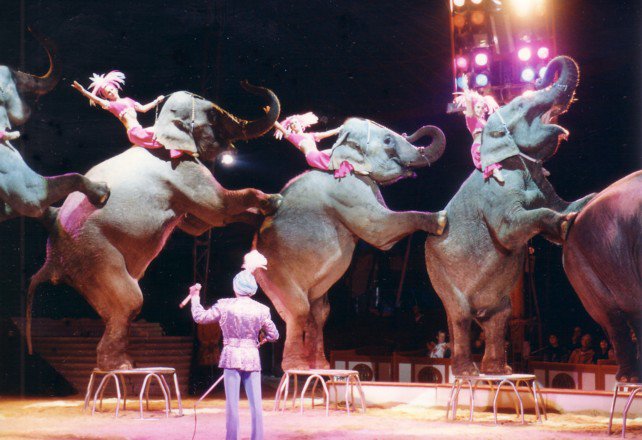

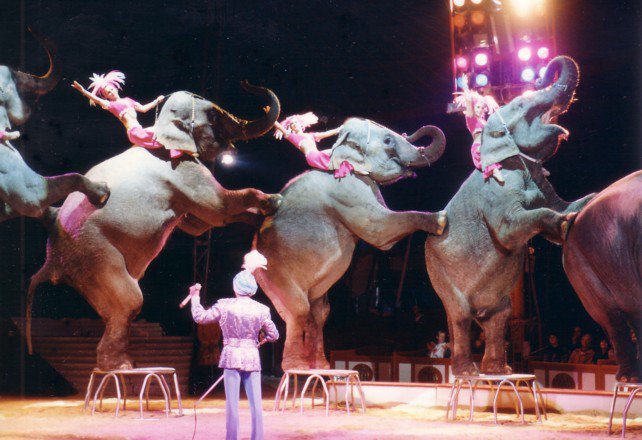

In Banda’s shows, the elephants took on a new life, moving away from the traditional idea of an elephant, that of a slow and ungainly animal. Banda’s elephants were trained to move fast in a small area, but were graceful as they danced with a chorus in harmony to sounds and lights. This became one of his best performances: elephants with a cabaret of dancers and elephants performing tricks in the mist, without either vocal or visible guidance from Banda.

What Would Living In a Circus Have Been Like?

Books and movies have created an idealised notion of what living in the circus was like. “Everything gets glorified in movies thanks to Hollywood. It was definitely not as romantic as people make it out to be. The old westerns and movies based on circuses are mostly fiction,” Banda laughs.

“Back in the day, there was no running water in the caravans. There were washing busses and we made use of public taps for water,” elaborated Banda. “Electricity was cut off by night and the front seating area had to be turned into a bed by night,” he said.

A typical day for Banda began at 6 in the morning. Feeding the elephants, playing with them and even cuddling them and tending to their needs if they were sick or ill. The rehearsals took place daily, regardless of the fact that the conditions were never stable and the environment and surroundings ever changing. There were at least two shows in a day, one at 3pm and the other at 8 – at times even three shows during the weekends, with a morning show at 10. This meant getting ready for the show in full gear, and not just for the performers but also for the animals!

“It takes endurance and patience and most of all, team work with strangers. Most of the shows and acts change annually but you need to depend on and trust your partners,” Banda said.

Was it difficult living in a circus? Banda chucked in amusement. “I didn’t know any better. It wasn’t hard for me, it was quite normal and even mundane because it was ‘normal’ to me,” he said.

“I think, as my parents grew older, they came to realise that comfort was missing,” Ganesha added. “Things like a stable surrounding and friends they could spend time with for more than just a season. But in general, my family never felt as if we missed out on something or had a hard life. On the contrary, we were always busy meeting new challenges and unexpected difficulties and it was a life full of joy and amazement. We were all quite content.”

A Circus of Anecdotes

Both Banda and his father Epi lived exceptional lives. When asked if WWII had an effect on the circus, Banda responded with an amazing story of Epi’s bravery. “My father was quite popular at the time. All the ladies loved him. He was exotic, brave and untouchable,” Banda explained. “Despite the war, the circus went on as usual, except during air raids when everyone ran for cover. This was Nazi Germany and my father knew quite a few heads of the regime, but he helped many Jews cross the border. He knew what it was like to be at the bottom, so he used his influence and dropped a few names where necessary. He hid Jews in his elephant trailer behind balls of straw and helped them across the border whenever he went abroad. My mother told me that she never feared getting caught as Epi’s confidence convinced everybody. He did this for five years,” he said.

Banda’s own life is quite colourful. He met his wife Dagmar at Zirkus Busch where Banda trained elephants. It was instant love. She grew up in East Berlin and joined the National Circus School and trained as a horse rider. Her act was toe dancing on horse-back in a tutu. In 1956, her group Truppe Case was contracted to the same circus Banda worked in. In 1958, Bodidasa Suwaneris, Ganesha’s brother was born. Dagmar’s family was not too happy – the couple just had a child out of wedlock and what’s more, they disapproved of the dark skinned Banda. “It all changed when my father helped her flee East Germany and helped support her family stranded behind the wall,” Ganesha explained, adding that their wedding was delayed because Epi was still touring and was unable to take time off. They finally married in 1959.

Banda recalls a time when both he and his wife were practising with the elephants at the winter quarters, where all the animals were housed, when the lions suddenly made an entrance. The caretaker of the lions had not shut their cages properly and the lions had broken out. “Arriving in the ring where we were rehearsing, they must have thought it was time for breakfast and tried to attack me,” Banda said. But before they could do so, one of the elephants rammed the flank of the lion and hurled it so far that it landed with a thump. “It fled, panicking, along with the other lions, right back into the cage. The lions looked like they never wanted another excursion ever again,” he laughed.

The dangers and excitement of circus life was also peppered by a few tragedies. Epi sold the elephant he brought from Sri Lanka, which he had taken with him to Hamburg and America, to buy his way out of his contract and finance his travels back to Europe. Unfortunately, his elephant did not perform the head trick with the new owner. The result was that the new owner’s head was crushed and the elephant was shot.

When Banda retired in 1997, one of his most valuable elephants, an African cow named Layla, became untameable. When Banda first worked with Layla, she was always in chains surrounded by at least four men. In next to no time, Banda won her over and she became his pet elephant. “She would even defend him from me,” Ganesha added. “She made sure all the elephants did what my father wanted them to do. They had an amazing bond.” When Banda retired, however, she was given over to a zoo, as she could not be tamed. “He transported her there and did what he always did. He left after he had introduced to her the new space and the new caretaker. I couldn’t believe it when he came back from the Naples Zoo without shedding a tear. I don’t think he could believe it either.” Layla, however, did not take to her new surroundings. Within weeks she became apathetic and stood only in one corner. She barely ate anymore. The zookeeper called Banda when Layla no longer got up in the morning, although she wasn’t an old elephant. Banda flew to Naples and what he saw broke his heart: he spent hours sitting beside her, touching her and talking to her softly. Layla had held on until she got a chance to say goodbye to Banda and for the first time in Banda’s life, parting with an elephant resulted in a death.

Remarkable Careers

Epi and Banda worked at a number of circuses during their careers. According to Banda, Epi claimed to have made himself 10 years older than the date of birth (1890) registered in his passport and said that he came from a wealthy Kandyan family, although Ganesha doubts this assertion. While working with Mr. Hagenbeck, he was offered to train elephants for Circus Busch. From 1928 – 1930, Epi was in America working with Ringling Bros and Barn & Bailey Circus but disliked America. “That was a time of racial segregation in America. He felt very uncomfortable there. In Europe he was a star, the exotic elephant man, and was treated with respect. In America, he was just a non-white-male worker,” Ganesha explained. Epi returned to Circus Busch in 1928 and stayed on until he retired in 1969.

By 1956, Circus Busch had 8 elephants and an ever growing demand for their act in many countries outside Germany. The father and son duo split in two, with 4 elephants remaining at Busch with Banda while Epi went abroad with the other elephants to countries like Poland, Romania, Bulgaria and Hungary. “During winter, when the travel season was over, they were hired by circus houses (buildings providing theatre and sporting events) and the group united and stayed at Budapest, Prague and Warsaw.

By 1962, Banda had decided to move on. He no longer wanted to be apprenticed to his father. He wanted to move out of his father’s shadow, especially now that he had started his own family. He got his chance to train a baby elephant at the Swedish circus Trolle Rhodin but the tide was against him. “He had quite a difficult time,” Ganesha explains. “There weren’t that many circuses with elephants to begin with for there to be a shortage of trainers.”

Banda worked in many circuses after that. He trained 30 horses at Franz Althoff’s circus in West Germany in 1965, then worked with the Italian circus Royal Americano in 1967 and in 1971 he was hired by the Italian circus owner’s cousin and began training 25 elephants at Circo Americano with Banda’s son, Bodidasa, as his apprentice. There, father and son worked in two groups with Bodidasa staying with a group of 12 elephants in Italy while Banda worked away from home, mostly at Circus Scott in Sweden or Bouglione in Belgium/France. “It was during this time that my father started trying out more humane ways of handling elephants. Sweden was very liberal. He was allowed to take them for walks and they could graze freely and swim in rivers,” Ganesha said.

Due to economic problems in Italy, the Vidanes then moved to Switzerland where Banda worked as a consultant to Louis Knie from Circus Knie. They trained and taught animals, but did not perform as they did before. Although the money was good, Banda was not happy – he wanted more. He missed the spotlight.

Banda’s big break came in 1982. Circus Krone was having trouble with their trainer – this was just the chance Banda had been dreaming of. It was also where he met the tall, lean, African beauty Layla, who helped him with the herd. Soon, the largest group of elephants performing in the same ring in Europe was born. Banda’s performance included 15 elephants. Banda soon introduced training sessions that were open to the public, to make the process of training animals more transparent.

Every show was important for Banda – he had different shows for the season, travelling during summer and putting up shows in circus houses in winter. “All the shows had to differ and they all had to be perfect. He created things people have not seen before: tricks, costumes, lighting and music. It was a perfect melange,” Ganesha added.

On Banda’s 60th birthday, in 1997, he retired, saying goodbye to his fairy tale life in grand style: in a circus ring with his wife of over 40 years, presenting his last show. They took their last bow to Andrea Bocelli’s “Time to Say Goodbye” and in a frenzy of camera flashes, their fans ran into the ring with flowers and gifts. He ended his career having trained 75 elephants in total and fighting for more humane treatment of elephants.

After The Circus

When asked if he missed the circus, Banda chuckled in amusement. “You might as well ask a fish if he misses water!” he said.

“I think they find it a bit boring at home,” Ganesha added. “They miss their friends but maybe not the travelling. I think they miss all the great conversations and the crazy world they lived in,” she said. “It’s different for my mother. She’s a people person. She has her children and her grandchildren but my father doesn’t have anyone he can talk to with a deep hum or a squeak, like he did with the elephants.”

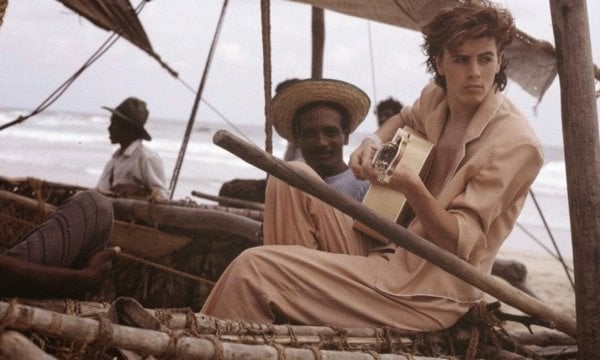

Banda’s travelling days are, however, far from over. Recently (2014), he visited his country of origin, Sri Lanka, for the first time in his life. He was pleasantly surprised. “Epi did not a paint a nice picture of Ceylon, pointing out why he left. Sri Lanka also has been negatively portrayed in the media as a primitive, backwards but beautiful country,” Ganesha said. “He loved the food and the sights and how friendly the people are. To him, his roots are in Sri Lanka.”

Both Banda and his wife Dagmar now live in retirement in Hannover, Germany, with their son Bodidasa, and often visit their daughter Ganesha in Berlin. “He never learned anything else and he never had a problem with animal rights. He respected his herd and was a part of it. Because he never let them suffer under any circumstances, he never understood why people fussed so much.” The elephants Banda trained were not born free, they were mainly elephants from zoos. “All they did in the zoo was graze all day. No mental input or entertainment, never mind physical exercise,” she said.

Working with elephants was Banda’s life, his natural inclination. A little question for the reader: can you guess why her parents named her “Ganesha?” His love for elephants is so strong that Ganesha said she often felt that “we knew he had something with them, a kind of bond, he would never have with us or anybody else.”

The video starts post 7 minutes in:

Images sourced from Ganesha Vidane