.jpg?w=1200)

Seventeen-year-old Nirushi* lives in a single-income household in Veyangoda, a small town in the Western Province. Her father is the family’s sole provider and his daily commute to work takes 90 minutes. Although a single source of income means fewer luxuries, Nirushi’s mother decided to stay at home in order to support the education of her two daughters. Nirushi’s parents are firm believers that giving their children a good education is the best way to secure a better future for them.

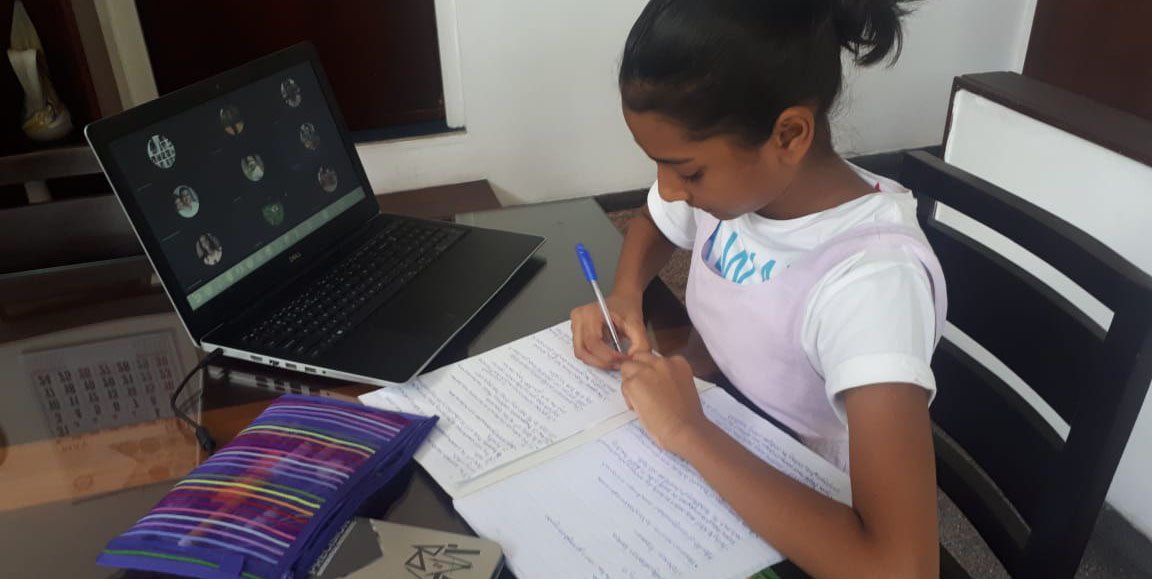

Due to the coronavirus pandemic, Sri Lankan schools — like many abroad — were forced to switch to an online learning system in early 2020. Nirushi was among the schooling population who are now learning in this new format, which she described as a whole “new experience”.

Internet Issues

“Initially it was hard to connect [to the internet] but after a while, the experience got better,” she said, adding that she did have connectivity troubles on and off right through. The Nittambuwa area that Veyangoda belongs to is classified as semi-urban, but Nirushi’s experience is an indication of how underdeveloped the online infrastructure is in several parts of the island.

Seventeen-year-old Ravindu* lives in Thalawathugoda, a suburb of Colombo, and attends a private school in Borella. He will be sitting for his GCE A-Level examinations next year. “My area has a lot of power cuts,” he said, “although [through the lockdown], the internet connection, surprisingly, has been fine.”

However, when asked about how other attendees’ connections affected his learning he said, “Classmates [didn’t] affect it at all, teachers, however, if they have bad connections, will usually ruin the class as nobody learns anything!”

This is a prime example of how the learning process can be interrupted regardless of where you live or where you go to school. Ravindu and Nirushi’s experiences also show that even while an individual student may have no trouble attending an online school, difficulties encountered by their peers and teachers will affect their experience as well.

Quality Drop

Another common complaint among students was a notable drop in the quality of their education, compared to when they were physically attending school.

Ashanthi* (19) lives in Mahabellana near Bandaragama and said that prior to the pandemic. Like the other students, she faced issues with internet connectivity while school was conducted online, however, Ashanthi said, “I have [also] seen a decrease in the quality of education. One of the reasons for this is that we are not able to do some practicals related to the lessons, in the way we do it in school with a teacher.”

Dr Sujata Gamage, a senior research fellow at regional think tank LIRNEasia, said the government ought to prioritise getting A-Level students to school so that they are able to do their practicals. Dr Gamage has been researching the impact of COVID-19 on education, and her work culminated in a study on innovations in education in both Sri Lanka and Bangladesh during the pandemic, which looks closely at the role of ICT in education.

Solutions?

Sri Lanka has lifted the latest lockdown, and schools are in the process of opening once more to students. A vaccination campaign for students has also been launched, and the government hopes the country will soon be stable enough to recover from the impact of the pandemic. But since schools cannot open to full capacity due to health regulations that must still be maintained for as long as the pandemic rages, many schools are looking at hybrid models through which the school conducts classes both online and offline.

Towards that end, students themselves have feedback on how they would remedy the shortcomings they’ve faced thus far with the online schooling model. “Aspects that can be improved are mainly the interaction between teachers and students,” Ravindu told us. “Teachers should be far more interactive with their students, rather than just reading from a PowerPoint or giving printouts.” He explained that sharing a screen or having students print out papers does little to motivate them to learn. “They should find more engaging and interesting methods of teaching the students especially during a time where a student’s distraction is at its highest since they’re at home,” he said.

Transmission Method

What Ravindu describes is a ‘transmission’ method of teaching that has been prevalent in Sri Lanka even prior to the pandemic. “…teachers do this ‘transmission’ mode of teaching because they have to cover the syllabus,” Dr Gamage said. “If we just do this boring transmission style, children just tune out, they don’t listen. When you do activities you cover the syllabus in engaging ways and when it’s time to remember it’s easier to remember.”

In addition to this, a non-academic-related shortcoming of online schooling has revealed itself in the loss of the “school experience” and an overall lowered morale among students.

“This is my last year of school, so I have missed out on having those essential experiences people have before they leave school,” Ashanthi said.

Balance and Normalcy

Bolstering student morale and maintaining their motivation is key in ensuring a good work environment. [Students] should have a routine, get a little fresh air and exercise,” Dr Gamage said, which could retain a sense of normalcy for as long as online school continues.

The long-term repercussions of a learning population schooled in what they themselves describe as an inferior system are yet to be seen, but experts like Dr Gamage feel education authorities can still make the best of an unideal situation by adapting the existing curriculum to phase out transmission teaching and bring more interaction between students and teachers to improve the quality of students’ learning. The Education Forum Sri Lanka is already carrying out a pilot to demonstrate the concept.

.jpg?w=600)