If you have ever wired money abroad through a third-party company that is not a licensed bank or a financial institution, chances are that you’ve committed a crime.

Sending money abroad itself is not a crime. But using the informal undiyal or hawala system that bypasses legal systems, makes it one. What makes it more problematic is that these transactions can also include the exchange and trade of illegal drugs and weapons. and the laundering of money.

But despite technically being unlawful, using the undiyal or hawala systems (there’s really no difference) is deeply ingrained in Sri Lanka, which has made it difficult for authorities to eradicate the system completely. Every year millions in foreign currency are wired and exchanged using this system.

And now, given that the system’s notoriety increased over the last decade — especially, this year — the current government has renewed interest in shutting it down.

‘Don’t Trust The Government’

Rizvan*, a businessman in his 50s, told Roar Media the use of the undiyal and hawala systems had increased since the middle of last year. “People also don’t trust the government and the unwanted pressure it puts on them. That’s why they use it,” he said.

Rizvan learned about the illegal trade of foreign cash exchange from his father. His father learned it from his grandfather, his grandfather from his great grandfather.

While the undiyal/hawala system has been always used, it has seen a gradual increase since early 2021, when Lankans living abroad began using it as a way to offset the gradual depreciation of the Sri Lankan Rupee alongside the US Dollar. The simple and efficient undiyal /hawala systems were a fail-safe — a system that didn’t ask too many questions.

“People prefer to go through this because dealing with banks is seen as a hassle,” Rizvan said. “Even to exchange a few dollars, you have to go through a lot of paperwork. They [banks] ask for so many documents; evidence of how they earned the money etc. Because of that people don’t want to go through that hassle.”

The undiyal or hawala system operates outside the legal system and does not deal with licensed banks or other financial institutions registered with the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL). Instead, it works as a simple system that incorporates promissory notes to transfer and exchange cash, without physical money actually moving.

“They [also offer]a lower price than the banks,” Rizvan said. “If a bank is giving you LKR 100 for every USD 1, the hawalas will give you LKR 150.”

These attractive rates, the convenience, low cost, lack of process and paperwork, and above all, anonymity is what work to make the informal undiyal/hawala system so popular.

Banned But Still Active

In April 2022, the CBSL announced that it would ban all open account imports to stop the demand for unofficial transfers made through undiyal/hawala systems. In a press release, the CBSL said, ‘these transactions could be linked to drug trafficking and other illegal activities’ and requested the public not to fall victim to such illegal activities, whether knowingly or unknowingly. This was despite the system having many legitimate patrons such as parents sending money to their children living abroad.

In the release, CBSL Governor Nandalal Weerasinghe claimed that the country’s monthly remittances of USD 500 million had fallen to USD 300 million early this year, indicating the volume of cash that had flowed through unofficial systems. To circumvent this, Weerasinghe said banks had been asked by the Central Bank to give small volumes of dollars to parents so that the demand for undiyal falls.

The CBSL ban came after its officers raided a popular foreign exchange company in Bambalapitiya. The CBSL had received complaints that the company was offering higher exchange rates and had attempted to purchase foreign currency from its customers at a higher rate than the rate offered by a licensed bank, violating the Authorised Money Changers under the Foreign Exchange Act No. 12 of 2017 (FEA). In April, the company was suspended from continuing its operations.

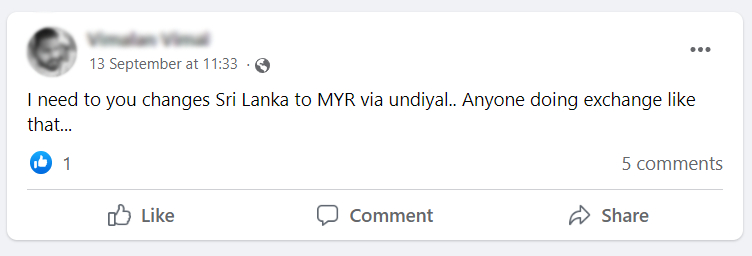

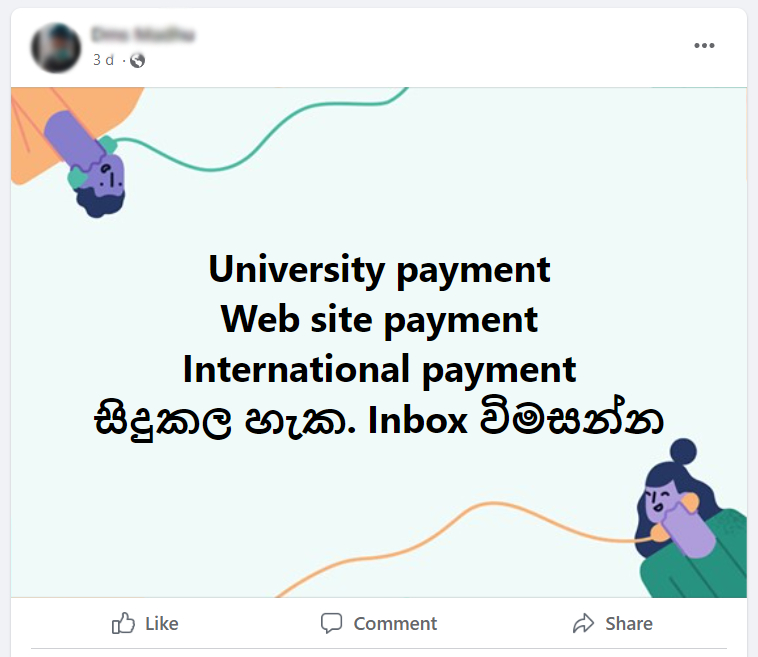

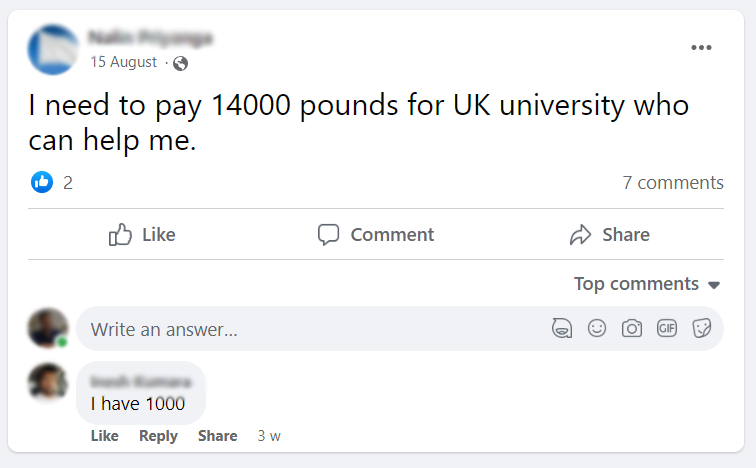

But while physical stores may be in danger of closure, the business thrives on social media.

Despite the ban, a number of individuals and groups on social media continue to sell and buy foreign currency at higher rates, in violation of the law. Many use social media and other channels to contact undiyal/hawala brokers to wire money to different countries or receive cash.

The Impossible Underground Bank

The very features that make undiyal an attractive avenue for legitimate patrons also make it attractive — or rather infamous — for illegitimate users. Undiyal/hawala is underground banking and is even used by money launderers and terrorists who take advantage of this system to transfer funds from one location to another.

For example, in 2015, it was reported that drug kingpin Mohammed Siddeek had transferred at least LKR one billion, earned through selling heroin, from Sri Lanka to Dubai. In its report to the courts, the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) noted that the suspect had sent LKR 70 million in 2013, LKR 100 million in 2014 and LKR 255 million in 2015 through the undiyal system. The money laundering case involved a number of suspects, including hawala brokers and Siddeek’s dealer, Gampola Vithanage Samantha Kumara, alias ‘Wele Suda’.

The system, however, continues to draw in patrons, who use it because they feel they have no other viable alternatives. For many, the underground banking system is the only way that they can send and save money.

“I came here after spending over LKR 4 million, for which I had to get a loan,” Jehan*, a student currently in Japan, told Roar Media. “I have to pay it back. My parents cannot do that, so I am doing part-time work here. But I cannot send money directly to Sri Lanka because of the many restrictions. A person on a student visa is not allowed to work and send money back. That’s why I use this system.”

Gamini*, a blue-collar worker in the Middle East told Roar, “We don’t receive a massive salary doing labour work in the desert. We have to live off that salary and send some of it back home. So even if it’s a small amount, if we get something extra from the bank, it’s a big deal for us.”

The ease that comes with using the undiyal/hawala systems has made it difficult for the government to eliminate it completely, and despite increasing pressure placed on those who operate and use the system, it is clear the authorities are faced with a tough task.