“It’s pretty clear that Pfizer provides more immunity than Sinopharm. That was why I held back from getting vaccinated,” a 24-year-old told Roar Media on condition of anonymity. He was responding to questions on why he waited at least a month after Sri Lanka started vaccinating its youth population against COVID-19 before finally getting the jab himself.

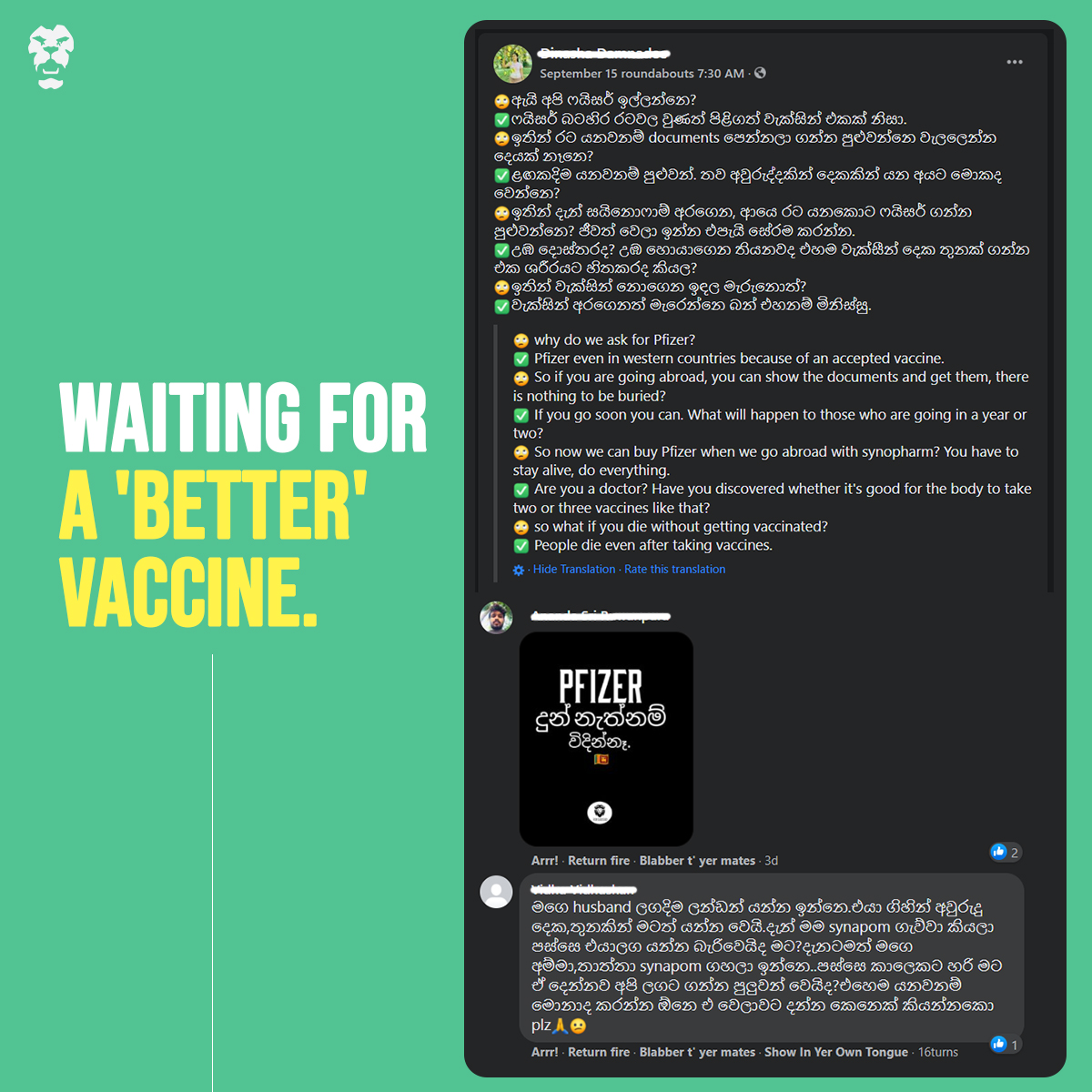

Similarly, other young Sri Lankans, who have hesitated to obtain the Sinopharm vaccine that is currently being administered, referred to multiple “research papers” which they say show that the Pfizer vaccine provides better immunity than other vaccines. An earlier decision by the European Union (EU) to not endorse vaccines manufactured in India, China, Russia and other developing countries has also played into their choices, even though at least 29 countries, including in the EU, revised their vaccine requirements earlier this month. However, China-manufactured Sinopharm, which is most widely available in Sri Lanka, is still not accepted by the United Kingdom, United States and Australia. Sri Lankan youth who aspire to leave the country when the pandemic is over, for employment, education or other reasons, would rather obtain a vaccine that is more widely accepted internationally.

“I don’t have any travel plans for now,” the 24-year-old told us. “But I’m curious to know what happens if you do go ahead with the Sinopharm vaccine and a year later, I want to travel to a European country, how would that work?”

Sri Lanka is now in its fourth lockdown and the government has been focused on speeding up the vaccination programme so that restrictions can be lifted as soon as possible.

Despite this, the prevalent vaccine hesitancy among youth has proven to be a complication. While some wait to receive the “best” possible vaccine, others have raised different concerns; last week, the Daily Mirror cited health authorities as saying that there were fears the COVID-19 vaccine would cause infertility. This could be a direct consequence of a much larger issue: conspiracy theories, misinformation, disinformation and other fake news concerning vaccines that are propagated on social media. Local health officials themselves recently said that they suspect that an “organised misinformation campaign” is to blame for the vaccine hesitancy.

Meanwhile, social media analysis carried out by Hashtag Generation, a youth-led organisation advocating youth civic and political participation, has uncovered interesting — and also concerning — findings. The group has noted not only a recent rise in conspiracy theories (‘Moderna vaccine manufacturer is an agent of Satan’), misinformation (claims those who received the Sinopharm vaccine can die from it), and disinformation (‘vaccine may affect the reproductive system’), but also an increase in the promotion of local remedies and home-made ‘COVID cures’ among social media users.

Among these are individuals who have opposed a vaccine due to fear of a variety of side effects, from the usual body aches to contracting COVID-19 regardless of inoculation. In some extreme cases, vaccines are being propagated as a method to control the minds of those who receive it. Others have refused the vaccine for religious reasons, or by opting for locally concocted, yet unapproved remedies.

“The selection of vaccines was particularly discussed on social media,” Prihesh Ratnayake, a social media specialist at Hashtag Generation, told Roar Media. “Since most European and Western nations, such as the US and Australia, are not accepting Chinese vaccines and Indian versions of AstraZeneca due to geopolitical reasons or vaccine nationalism, people who wish to travel abroad, especially to Western countries, [have] waited for Sri Lanka to receive Pfizer or Moderna.”

This ‘wait’ for better or more acceptable vaccines, as well as fears about side effects and efficacy due to misinformation or disinformation, has resulted in vaccination centres in several parts of the country receiving fewer visitors, despite an accelerated vaccination drive opening up for the youth on 3 September.

According to the Deputy Director-General of Health Services, Dr Hemanth Herath, not even half the population between the ages of 20 and 30 has received their first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine.

“We are not happy with the rate at which those in the 20-30 age category are receiving their vaccine,” he told Roar Media. “Even though the rate of inoculation is increasing, it is not satisfactory, compared to the rate of the other age group [30 and above],” he said.

As of 28 September — four weeks since the country began vaccinating the 20-30 age group — only 48% of the age group has received their first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, Dr Herath said. Only about 13% of those in the category have received both doses.

“They are the ones who have received it [the vaccine] earlier [before vaccines for the 20-29 age group officially began] because they could not have received both doses in the past four weeks,” he explained.

This adds credibility to unconfirmed reports about a percentage of the youth who obtained their vaccines through various other channels, during the first phase of the vaccination process which focused on inoculating those above the age of 30.

However, there has been no official confirmation of that fact by the government, and none relating to an investigation into how vaccines set aside for one group — identified as more susceptible to the virus — were distributed to a separate group.

Meanwhile, the government is now reportedly considering a vaccine mandate. Whether this materialises or not, health authorities have emphasised that the solution to Sri Lanka’s COVID-19 crisis lies in vaccination. “None of the reasons put forward by those who have not received a vaccine are acceptable to the Ministry of Health,” Dr Herath said, “because why we are insisting on the vaccine is to protect themselves, as well as to protect their loved ones at home.”