Sri Lanka’s economy, which struggled amidst the constraints of nearly three decades of civil conflict, benefitted very briefly from the “peace dividend”, following the end of hostilities in May 2009. The following three years saw one of the most rapid rates of economic growth in the world, the country becoming a “middle-income economy”. However, from 2012, growth fell back to less dizzying elevations. Several factors, including corruption and political incompetence, were adduced for the island’s economic growth not being sustained, but it is clear that its economy has fundamental structural problems which affect its development.

Sri Lanka is finding it increasing difficult to pay for its imports. Image courtesy lankabusinessonline.com

The country is finding it more and more difficult to pay for its imports, and relies increasingly on remittances from overseas workers. Foreign employment now accounts for about 24% of Sri Lanka’s labour force. This means that the country has a structural unemployment rate of 28%, or even more when underemployment is taken into consideration, indicating the lack of economic development. Paradoxically, the industrial sector faces a labour shortage.

To add to the nation’s woes, this year has seen a contraction in overseas remittances for the first time, combined with a decline in exports earning. Export performances have been inadequate for some time, reflecting structural problems in Sri Lanka’s economy.

Manufacturing Base

Prof. Gehan Amaratunga of the Nanotechnology Institute (SLINTEC), talking about disruptive technologies to the annual sessions of the Institute of Chartered Accountants in 2014, pointed out that Sri Lanka’s economy has about the same gross domestic product (GDP) as Taiwan had, some 35 years ago; an island of similar size, with the same population, which achieved five-fold economic growth in three decades. Sri Lanka could, he felt, be in the same position.

There is a difference, however: innovation does not take place in a vacuum. It is significant that, while Ray Wijewardene developed the technology for two-wheeled tractors, the country does not produce them. J.C.V. Chinappa developed solar-powered refrigeration technology, but Sri Lanka does not use it.

Taiwan’s manufacturing sector in 1981 accounted for 29% of GDP, compared to Sri Lanka’s 17% today. And garments only accounted for a quarter of Taiwan’s manufacturing, in contrast to that sector’s preponderance in Sri Lanka’s industrial economy. The productive sectors, agriculture and industry, contributed 56% of Taiwan’s 1981 GDP, whereas in Sri Lanka, it is the services sector which accounts for 58%.

Renowned economist S.B.D. de Silva points out that, although we have a large garment industry, it has not developed a domestic supply chain, and consists mainly of imported inputs. A developed manufacturing base requires an integrated supply chain, which includes machinery and equipment. “Sri Lanka does not produce a single needle,” he complains, “to supply to the sewing machines of the garment factories.”

The garments industry uses chlorine and caustic soda, once produced by the Paranthan Chemicals factory, but no attempt has been made either to restart it or to set up new plant adjacent to other salterns which can provide the raw material, brine.

Ilmenite sand mining. Sri Lanka is not deficient in raw materials – we just need to utilise them well. Image courtesy lankamineralsands.com

Sri Lanka is not, as the conventional wisdom has it, deficient in raw materials. Over 20 million tonnes of iron ore exist in several locations around the country. Apart from Ilmenite and Thorianite sands on the north east and the south west coasts, from which can be extracted the high-value heavy metals Titanium, Beryllium, Zirconium, and Thorium, there are a variety of other industrial raw materials available, which should be harnessed to value-added industry. Graphite, for example.

Industrialisation

In 2005, a UNDP team led by economists Howard Nicholas and W.D. Lakshman determined that Sri Lanka needed a strategy for rapid and sustainable growth of per capita income levels.

“Such a strategy,” they concluded, “should be founded on export-oriented (and import-substituting) industrialisation, and the promotion of domestic food production. Rural industrialisation should be promoted, but attention needs to be paid to the nature of the products produced and the technologies adopted.”

However, that was not the policy adopted. Indeed, Successive governments have followed, essentially, service-based growth models. Trade, banking, and property markets rather than agriculture and manufacturing have been seen as driving the economy.

The Mahinda Chinthanaya envisaged development on the basis of transforming Sri Lanka into a “Mega Global Hub” in aviation, maritime, energy, knowledge, commerce, and tourism. Earlier this year, the new government intimated that it had abandoned this concept in favour of a “Triple Hub”, the so-called “Western Region Megapolis” being developed as a maritime, aviation, logistics, and trade hub of Asia.

Practical Economics

Economists such as Nicholas are not convinced that this is the right way forward.

“I think we need to go back to a practical economics which really works,” he told Abacus magazine. “I tell Sri Lankans, ‘Industrialise, go for manufacturing’, because there is no alternative. All the other things Sri Lanka has been taught is just not so. It simply has not worked anywhere else, will not work, there is only one strategy, to learn to get to grips with it.”

Why the lack of emphasis on manufacturing? Experts proffer various explanations. Nicholas thinks is it is because there are vested interests who don’t want such a strategy.

“It is all the same stories,” he complained. “I remember in 1994, ‘we can become a computer programming hub for India’. In 1995 ‘we can become a financial hub for India’. It is such nonsense. Anyone travel to Mumbai recently? Sri Lanka a financial hub for India? They must be out of their minds.”

Power-sector consultant Tilak Siyambalapitiya thinks that it is because of the high cost of energy inputs; our economy is service-oriented, so we use less electricity.

“To produce a dollar worth of output from services,” he says, “requires less electricity than to produce a dollar worth of output from manufacturing. Why we are not getting industries into the country, despite having raw materials for them, for example in the ceramics, glass and cement industries? This is because of the high energy cost. Energy is too expensive.”

Agrarian Backwardness

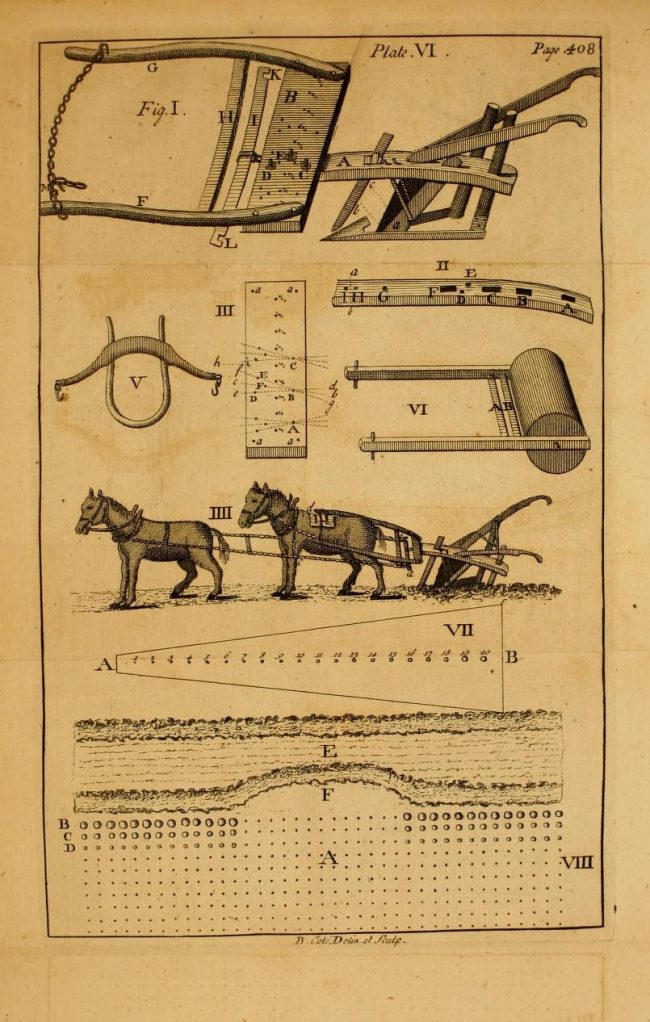

However, S.B.D. de Silva, who was a former deputy-director of the Hector Kobbekaduwa Agrarian Research and Training Institute, thinks it is because of the backwardness of agricultural sector. He points out that the Industrial Revolution in Britain took off on the basis of the development of the agricultural sector. The introduction of a year-round, four-course system, involving rotation of turnips, barley, clover, and wheat crops, combined with the horse-hoeing agricultural mechanisation of Jethro Tull, increased the productivity of farmers, releasing labour for the new factories, as well as creating a market for industrial goods. However, he says, our agricultural sector remains backward and pre-capitalist: farmers do not have enough surplus to become a major driver of investment or to provide a sufficient internal market.

Jethro Tull’s Plough, which contributed to Britain’s Industrial Revolution. Image courtesy wikimedia.org

The World Bank shares this view of the lack of development in agriculture. It believes that Sri Lanka’s agricultural sector is at a “strategic cross-road”. Although the long sought-after goal of rice self-sufficiency has been achieved, it says,

“… the share of population employed in agriculture has remained at about 30 % over the past 10 years, even as the share of the sector in national GDP has continued to decline to 10 percent. This implied and persistent inequality adds to the urgency to rethink the strategic direction of future agricultural development – how to sustainably increase rural incomes and promote the development of a modern agriculture sector that meets the needs of an upper-middle-income country that Sri Lanka aspires to be.”

In June, the World Bank approved a $125 million credit line from the International Development Association to assist Sri Lanka to modernise its agriculture sector and make it more efficient, more responsive to consumer demand, and more environmentally sustainable and resilient to climate change. The project, to be implemented in five provinces, is intended to benefit 50,000 smallholder farm households directly or indirectly. It will fund agricultural value chain development to promote commercial and export-oriented agriculture, focussing especially on higher value fruits and vegetables; improvements to productivity and diversification of growing patterns through modern agriculture technology demonstrations in the project areas; new institutional arrangements in the form of farmer organisations and farmer-agribusiness partnerships; and policy development, enabling the Government to decide the future direction of the agricultural sector.

Structural Reform

Rice combine harvester, Hambantota. A majority of Sri Lankan farmers are involved in paddy farming at a subsistence level.

However, this initiative depends heavily on dry-land cultivation of alternative crops, not on reform of the existing paddy sector subsistence economy. S.B.D. de Silva thinks that there needs to be deep-going structural reform.

He argues that Sri Lanka’s economic woes can be traced back to our inability to break out of the constraints of a colonial economy. The majority of farmers are involved in paddy farming at a subsistence level – most of their produce is for home consumption, and only a small surplus is left over for trading. Traditional farmers do produce for the market, but this is in subsidiary crops in their home gardens and in their slash-and-burn chenas in the forests, which also provided fruits and herbs, while protecting the watershed.

The British-enacted Crown Lands (Encroachment) Ordinance of 1840 and Wastelands Ordinance of 1897, expropriated the forest and common lands of the farmers, effectively cutting them off from their market-production. This colonial legacy remains. The primary problems associated with the traditional paddy sector, according to de Silva, are farmer indebtedness and labour underemployment. They both arise partly from the fact that farmers are dependent on the monsoon. Sri Lanka’s irrigation system does not provide sufficient water for year-round cultivation, and the nature of the paddy field does not allow for off-season crops. Hence, for the inter-monsoonal months, farm labour is unemployed – which does not show up in the unemployment figures. The seasonal nature of their unemployment also does not allow them to join the industrial labour force, resulting in an imbalance between job vacancies and labour availability.

The imbalance between industrial labour shortage and rural underemployment crops up even in the apparently advanced industrial economy of Thailand – which has not carried out reforms in the agrarian sector, unlike the East Asian countries. The result is a manufacturing sector heavily dependent on exports, lacking an internal market and facing a chronic labour shortage.

Practical Solutions

According to traditional paddy variety farmer H.G. Maithripala, of Anamaduwa, the problem can be alleviated if there is an off-season crop. In irrigated dry zone areas, this can be done fairly simply, by starting the crop earlier. The Government officers concerned must be galvanised into action in February (for Yala) and in August (for Maha), when farmers have plenty of time on their hands, to arrange Seasonal Meetings (Kanna Resweem) long before the rains arrive, to assess the likely weather patterns and to arrange for adequate supplies of seed paddy, earlier than now. At present, the officers are only galvanised at the onset of the rains, when the farmers need to be busy in their fields; they need to be instructed to start discharge of irrigation waters early, to enable off-season cultivation, so tanks can be replenished in time for the main season.

The problem can be alleviated if there is an off-season crop – H.G. Maithripala, traditional paddy farmer. Image courtesy writer.

Otherwise, it is necessary to find markets for and popularise the cultivation of alternative, wet-land crops, which may require considerable research; attempts to grow moong beans on paddy fields have been less than successful. One alternative is to popularise dry cultivation of paddy in the off-season.

Maithripala thinks that the main solution to indebtedness is to have a dynamic, limited purchase guaranteed-price scheme. This would entail early discussions between the purchasing officers and groups of farmers to determine what the harvest is likely to be. The officers need to determine an amount to be purchased, which will leave each farmer with adequate stocks for family consumption and sale on the open market, if necessary. The farmers need to be given some lead time to prepare their paddy for collection, during which time the officers need to arrange the funds for payment on the nail, to prevent indebtedness to usurious lenders.

East Asian Model

We could look at how the East Asian “Tiger Economies” industrialised. South Korea and Taiwan carried out land reform far deeper going than Sri Lanka’s (the land ownership ceiling was three hectares in their case, compared to our ten hectares for paddy land), and modernised their agrarian sectors. The resultant, broader land-ownership created an internal market which, in tandem with import restrictions, served as a basis for rapid industrialisation. Once the industrial foundation was laid, an export-led strategy was adopted, but the internal market was protected.

Sri Lanka could well follow a similar strategy. A consumer goods sector, serving the agrarian market, could be constructed, using machinery produced by a heavy industry sector built upon the basis of the necessities of a mechanised agrarian sector.

In future, it may be necessary to consider the economy holistically, with an understanding of how each sector affects the others. An “ecosystem” for rapid and self-reliant development needs to be created, and this requires state planning, as for example was done in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, and arguably, Singapore. Sri Lanka has the know-how, the personnel and even the mechanisms in place to do so, but has lacked the political will.

Featured image courtesy thesrilankasceneries.blogspot.com