In February 1964, Patrick McNee and Honor Blackman, two of the stars of the British television action series The Avengers, came out with a hit single, Kinky Boots. In this case, “kinky” meant aberrant or unusual sexual behaviour and the boots in question had been used by dominatrices, ever since Émile Zola’s 1868 novel Thérèse Raquin. The song led to the boots being enormously popular among women.

It contained the considerably significant – in view of what happened later – lines:

“Kinky boots,

It’s a manly kind of fashion that you borrowed from the brutes…”

In 2005, Miramax released the film Kinky Boots, which made a modest USD 10 million at the box office. However, it spawned a Broadway musical which became a smash hit, grossing USD 229 million so far. The New York Times said that it brought “real-world problems like chronic unemployment, financial distress and the collapse of manufacturing to the Broadway stage”.

Kinky Boots musical at Toronto theatre. Image credit: wikimedia.org

Collapse Of Manufacturing

The inspiration for the film and the musical came from the real-life story of the W. J. Brooks company, a Northamptonshire shoe manufacturer. In the 1990s, fifth generation shoemaker, Steve Pateman, the company’s Managing Director, faced a problem. A German buyer had cancelled an order for 5-6,000 pairs of brogues, W. J. Brooks’ traditional hand-made product, but the raw material had already been bought.

It looked like Pateman would have to close down the factory, as several other companies in Northamptonshire had already done. With a nearly 900-year tradition of cobbling, the area had seen shoe factories spring up after 1858, introducing machine production. However, by the 1990s, cheap East Asian imports and rising production costs made these factories unable to compete.

Out of business – abandoned Northamptonshire shoe factory. Image credit: flickr.com/tonp

At that point, Pateman received a telephone inquiry from a fetish shop in Kent, asking about female shoes in male sizes. The query opened up the vista of the market in erotic footwear for W. J. Brooks. The factory began producing “kinky boots”, for which they found a huge overseas market – 90% of production went to Germany and Poland.

However, a few other Northamptonshire manufacturers went about it a different way, from mass-commodity to specialist production. They increased the quality (and hence the price) of their brogues, rejecting modern machine methods for traditional hand-crafted products. They have found a huge market among the nouveau riche of East Asia.

What W. J. Brooks and the other firms had in common was that they switched from the mass market to manufacturing for a niche – although the niches were somewhat different.

Sri Lanka’s Economic Crisis

Sri Lanka, paradoxically, also has a problem with production costs. That the island nation faces a mammoth economic crisis is no secret. Its predicament arises from its inability to generate enough overseas income to pay for its domestic consumption. Economists such as Howard Nicholas, W. D. Lakshman and S. B. D. de Silva identify the failure of the country to industrialise as the root cause of this predicament. The manufacturing sector has, since the early 1980s, contributed less than 20% of the gross domestic product, and has been growing considerably less rapidly than GDP.

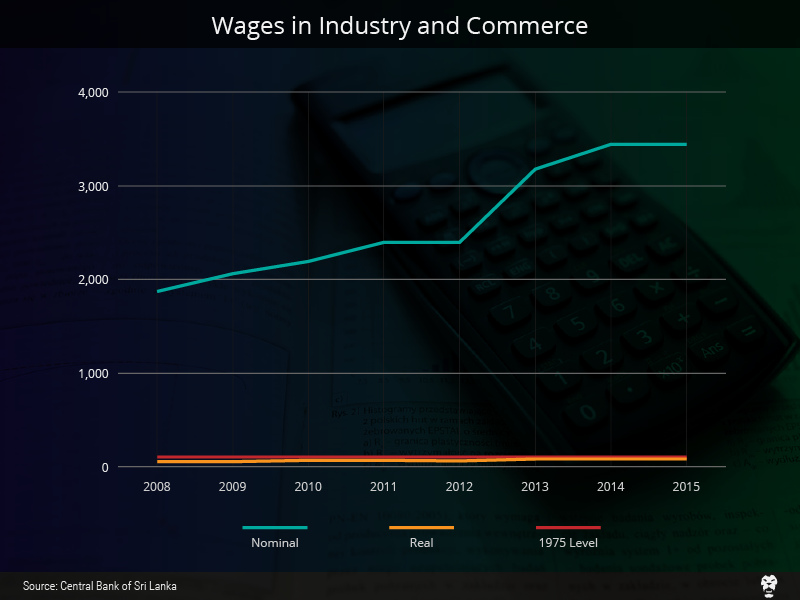

The paradox is that, although Sri Lanka has not industrialised, manufacturers face rising production costs and labour shortage. According to data in the Central Bank’s annual reports of 2010-2015, although wages in private sector industry and commerce have been increasing, they have not kept pace with the rising cost of living. As the table shows, real wages have not yet caught up with their 1978 level. Hence, the haemorrhage of workers overseas (mainly, but not solely as domestics) and the consequent labour shortage.

The international financial institutions, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, have no answers, beyond repeating out-of-date platitudes, including removal of tariff protection and reducing the government’s role. Their advice has, in the past, proved disastrous, as Howard Nicholas clarified to the 2017 Economic Forum. Nicholas advocates the development of manufacturing as the only way forward.

Sri Lanka certainly has many advantages for manufacturers: it sits astride the major East-West shipping route, it has an educated, trainable, and flexible workforce, and labour unrest is minimal. On the down-side, there is hardly any manufacturing in the vital electronics sector – which collapsed in the immediate post-1977 period. More importantly, it lacks an internal market, since the agricultural sector remains enchained in the colonial economic pattern.

Nordic Niche Model

The Nordic model illustrates a way forward for a small market with relatively high labour costs. Lacking large internal markets, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden responded to the complexity of modern production and supply chains by developing niches.

The pattern was established by Sweden. Sandvik, started in 1862 making specialised steel, and today remains specialised in materials, mining, and machine tools. The SKF company, today the world’s largest manufacturer of bearings, began in 1907 with a factory in Gothenburg to manufacture the double-row ball bearing invented by executive director Sven Wingquist. The other Nordic countries followed suit much later. Typically, in Denmark in the 1950s, the release of labour from the agricultural sector due to the latter’s mechanisation fuelled a wave of industrialisation. This was based on small, high-technology firms involved in manufacturing to fill market niches in such product areas as radiator valves, specialised pumps, or pharmaceutical preparations. For example, Danfoss developed an expansion valve for refrigeration and heating equipment in the 1930s. In the 1960s and ’70s, Sri Lanka’s refrigerator and freezer manufacturers used the company’s equipment. Today, Danfoss has 50 product lines and invests heavily in innovation.

Original Danfoss compressors factory. Image credit: wikimedia.org

The Nordic countries boast an impressive number of world leaders and are coping well with the pressures of globalisation and the long recession. Sweden’s top niche companies are in heavy industry, producing specialised steels, mining equipment, and machine tools (e.g. Sandvik and Atlas Copco). Denmark has major players in insulin (Novo Nordisk has half the world’s production), hearing aids (Oticon), toys (Lego), and wind-power (about 200 companies). Finland has Kone, a top lift and escalator company, as well as Nokia and Rovio (the creator of Angry Birds). Norway has Kongsberg automotive, supplier of automotive accessories and control systems, Møre Trafo, making transformers and substation, as well as numbers of small companies supplying ships, engine parts, and parts of offshore oil rigs. Even tiny Iceland has used its own natural resources to build up an export base in geothermal energy. However, most of its manufacturing base has been established around the fishing industry.

A well-paid and high-quality workforce, working at the high-technology end of manufacturing, provided the foundation of the Nordic niche strategy. It also depended on the government creating a stable industrial ecosystem, achieved through a system of state-interventionist measures, including an administratively-set, low-level of interest; a reduction in the role of direct foreign investment, of private-sector banking institutions and of the stock market; state-owned development banking operations; and of course heavy government investment in infrastructure – both “hard” and “soft”.

Uplifting Story

Sri Lanka already has considerable experience with niche manufacture, from jock-straps to joystick gyroscopes for aircraft. The number one success story has, of course, been upmarket brassieres, which have been the Sri Lankan garment industry’s version of kinky boots.

“Sri-Lanka is renowned as a lingerie hub,” says Dian Gomes, head honcho of Hela Clothing, “with many large vendors in the industry producing bras serving customers such as Victoria’s Secret, M&S, Triumph, and Calvin Klein.”

From his days at MAS, Sri Lanka’s top garment manufacturer, Gomes has been intimately involved with the development of the manufacture of high-quality fashion undergarments. MAS concentrated on developing its own technological and design capability – initially getting down lingerie designers from Britain. The effort paid off.

“Sri Lanka has become known,” he says, “as a go-to place for technically advanced products such as bras due to the talent pool, skills, and the verticality we have built.”

Since joining Hela, originally known as a kids-wear manufacturer, Gomes built on his experience of underclothing manufacture.

“In 2015,” he says, “we embarked on producing lingerie and setting up an intimates wear cluster within the group. Today we have extended our product portfolio to manufacturing bras, panties, boxers, sleepwear, casualwear, and swimwear.”

Lingerie is Sri Lanka’s most prominent niche sector. Image courtesy Hela Clothing

Even in a short time, Hela has experienced rapid growth. Gomes is gung-ho about the future:

“Hela is focusing on setting up a strong foundation for the company to grow by developing our manufacturing capacity to be on par with the best in the world. Consequently, in 2015, we set up the infrastructure to facilitate the growth by investing in people, processes, and systems. [Last year] was the year of expansion, where we grew aggressively, adding manufacturing plants, strengthening our customer base, and adding to our product portfolio, growing the intimates division to 100 million. [This year] is a year where we consolidate.”

From Zips to Air Bag Sensors

The garment industry itself has provided opportunities in its supply chains for niche manufacture in Sri Lanka. Naturub Industries is an outstanding example.

In the 1970s, Tissa Eleperuma, with two classmates, began a small-scale enterprise (the name comes from “natural rubber”) to manufacture toy balloons, with no capital and no bank backing. They would cut up the waste balloons with scissors to make rubber bands. In the 1980s, with the rise of the garment industry, the company switched to apparel accessories: zips, elastic, thread, and belts.

It took many years of strenuous effort, but the company grew steadily and is now a group with over LKR 5 billion turnover. Naturub is the major apparel accessories supplier to Sri Lankan garment factories, also exporting to Bangladesh, India, Morocco, and the Middle East. The nominated supplier for high-quality buyers such as Marks and Spencer, Calvin Klein, Tommy Hilfiger, and Victoria’s Secret, the company employs nearly 2,000 workers in its Sri Lanka factory and a further 800 in Chittagong, Bangladesh.

Naturub only assembly-line produces some basic items, which are not order-specific or customer-specific. More than 90% of their orders are customer specific – with prescribed colours and designs – which are made to order.

At the other end of the scale, there are niche industries supplying export markets, with virtually no input from the domestic economy, one instance of which is Lanka Harness, which manufactures impact sensors for air bags and seat-belt switches, for motor vehicles.

Managing Director Rohan Pallewatte’s business took off with a Japanese investment of USD 8 million in 2002, when it began work at a factory in Biyagama. Now, Lanka Harness has two factories, employing 350 people – total employment is 1,000, including subcontractors – making about 2 million sensors per month. Last year, the firm had a turnover of about USD 40 million, supplying to Aston Martin, BMW, Fiat-Chrysler, Ford, Honda, Nissan, Saab, Toyota, Volkswagen, and Volvo. Pallewatte now plans to buy out the firm’s Japanese principal.

Appropriate Workforce

Lanka Harness’ experience brings out some of the positive qualities of the Sri Lankan workforce, suiting it uniquely to high-technology niche production. Pallewatta thinks that Sri Lankan labour is intelligent.

“To train a girl for a Juki machine in Bangladesh takes about six months,” he says, “but in Sri Lanka, [it takes] only three weeks. So that kind of cultural difference exists. You cannot take a blanket view of labour across the world.The uniqueness of what I do is its quality requirement: one part per million (1 ppm) is the tolerance level, which is the highest quality rate anywhere in the world, as this is a device that can make a difference between life and death in an accident. Many said that it would be impossible to achieve this stringent quality standard with Sri Lanka’s existing work ethic and mindset.”

Lanka Harness uses the Japanese concept of Kaizen, small improvements, and has introduced process innovations continuously. It now makes products, which previously took 100 seconds to make, in 50 seconds. There is a structured system: anyone from the production floor level can suggest improvements to the existing processes, for which they are compensated adequately.

“We make the product according to drawings sent to us by customers,” says Pallewatte, “big companies like Nissan or Honda. We sit down and look at the practical problems we may face in production according to the drawings, which come from professional engineers. In most cases, there are errors in the drawings, which my production floor level people point out and are able to correct.”

This kind of lateral innovative thinking can be a great asset in niche production. It can aid in the flexibility of production, enabling families of similar products to be made using the same plant and machinery, thereby increasing the sustainability of the enterprise.

“We need to evolve as a solutions provider for highly technical products such as bras,” says Gomes, “and leverage R&D and innovation to keep adding value as a country.”

Of course, the state needs to do a great deal more in the way of creating an ecosystem in which niche manufacturers can thrive. Sri Lanka has a long way to go before it can catch up with the Nordic countries’ level of support for industry.

Editor’s note: This article previously stated that Naturub employed 8,000 workers in Chittagong. This has been corrected to 800.

Featured image: Scene from the film Kinky Boots (2005). Image courtesy imdb.com