Transacting online is not a new thing. Ever since the birth of Amazon and eBay, e-commerce has become almost synonymous with the internet.

Sri Lanka has its own share of successful home grown e-commerce startups (Kapruka, Takas, Wow) and with the entry of companies like Rocket Internet (Kaymu), we’ve now also got multinational firms looking to invest here. Bear in mind that Ikman, PickMe and Uber are also technically e-commerce startups.

They operate in different sectors, but they’re all local e-commerce startups.

But compared to other Asian countries, we’re laggards. For instance, consider India.

Indian e-commerce startups have surged way past us, despite both countries formally going online in 1995. In fact, e-commerce today has become a buzzword in the country across the Palk Strait. From FlipKart and Snapdeal to Ola Cabs and countless others, the number of tech startups sprouting in India is… well, a lot. According to PwC, the Indian e-commerce market was expected to be worth around USD 22 billion at the end of 2015. Of that, the retail (or e-Tail) market was expected to be worth around USD 6 billion.

So why can’t local e-commerce startups grow big enough to at least be mentioned in the same vein as their Indian counterparts? And more importantly, how did e-commerce become such a big deal in India, and what can we learn from them?

The most obvious reason is of course, the population. India has over a billion people while we have 21 million. And for those of you who skipped Maths, 1,000 million equals 1 billion. There is no way for us to catch up to India’s 375 million active internet users, unless we lease some deserted part of Central Russia and repopulate it or something. But beyond the numbers, there is something special about the demographics in India which we ought to look at, and it has a bit of a story behind it.

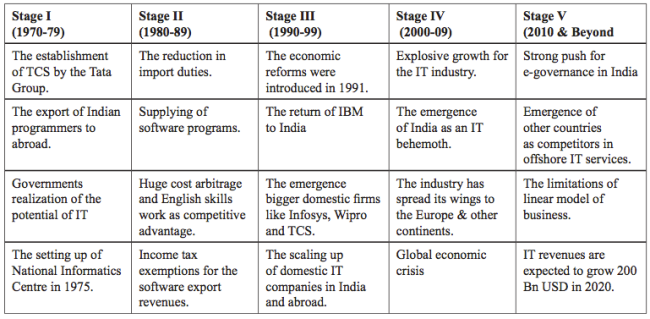

In 1990, the then Indian Government decided to make investment in IT a priority. The Government saw that information technology was the future, thanks to the efforts of the Tata Group (it’s actually quite interesting, click here to read in full). Consequently, the Indians invested in “Software Parks” which were basically BOI zones for IT companies. These IT companies then got to work with clients based in the U.S. Indian IT workers ended up getting ample opportunities to work on both offshore and onshore projects, which resulted in them becoming comfortable with the whole internet thing, which back then, was only for geeks.

Fast forward 10 years later and by the early 2000s, India had a young population and also a booming tech scene, mainly in cities like Bangalore and Gurgaon. Wages were also high in the IT sector (which by then was gradually moving from outsourcing to building their own products, known in business circles as “moving up the value chain”), which attracted hordes of young graduates who ended up inheriting the technological savvy and consumerism of their American counterparts. And that, people… is the unique situation we were talking about earlier.

The growth of the Indian IT industry, summarised. Image Credit: Global Management Journal / CII-KPMG

When tech savviness meets consumerism, it creates the perfect conditions for e-Tail and e-commerce to explode in growth.

Now again, we can’t replicate the population levels of our neighbour, nor can we deliberately go from having an ageing population to a young one. Even if we somehow could, it’s going to take a long, long time. But, we definitely can increase investment in IT infrastructure, which theoretically should attract companies and talent, in the end making everyone more comfortable with all aspects of the internet.

And now let’s shift to Colombo…

The Sri Lankan e-Tail market is worth around USD 25 million. Also, e-commerce is still very much in its early stages here. And there is a whole lot of potential, considering the fact that our retail market is worth around USD 7 billion. Plus, it can actually improve the efficiency of our economy, and help improve competition between SMEs and larger firms.

Given all its positive spillover effects on the economy, what more can we do to help the local e-commerce industry?

1. The banks, Central and Licensed, need to pull up their socks

Banks play a very important role in the functioning of an e-commerce site. They provide what is known as an Internet Payment Gateway or IPG, which is responsible for processing your credit card. If that’s too confusing, think of it basically as the card swipe machine at the cashier of your local Food City or Keells. The way things stand right now, it’s rather expensive for a group of college dropouts with no money to start an e-commerce firm, even if they had all the other necessary skills.

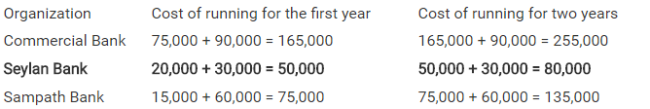

Our friends at ReadMe.lk broke down the costs of running an IPG. Note that most banks also require a fixed deposit of at least LKR 100K, in addition to the above.

All these costs put a lot of pressure on startups, which by nature must try really hard to make ends meet. They need to be really smart with how they spend their money, because otherwise they’ll go bust in no time.

Our banks also need to upgrade their design skills, ASAP. Why? Because good design can actually help to sell by inspiring confidence in the user. Lankitha Wimalaratne, CEO of Vesess (who were also featured on Lifehacker for developing HiveAge, an outstanding billing service for freelancers and small businesses) had this to say about Sri Lankan IPGs in his blog post:

“But the bitter truth is that we don’t see any future with them, either for us or for our clients, due to their extremely high costs (initial costs + monthly recurring fees + 3%− 5% transaction fees), underdeveloped APIs, terrible UX and lack of compliance/security. Worse still is the Sri Lankan IPGs’ unprogressive attitude compared to the other services we deal with from around the world like Stripe, PayPal, Authorize.net and SecurePay.”

Having said that, there’s not much of a difference between the attitudes of local banks and Indian banks. Here and over there, it is very much a tale of indifference towards startups.

But here’s where the two roads (stories?) diverge.

You know how they say that “Necessity is the mother of invention”? That’s what the Indians did. They invented.

When banks failed to accommodate startups, Indian entrepreneurs used their ingenuity to find a workaround. Local startups and established players like Flipkart took matters into their own hands and developed their own payment gateways. Of course, it was also super easy to find a world class software whiz to help out with the coding.

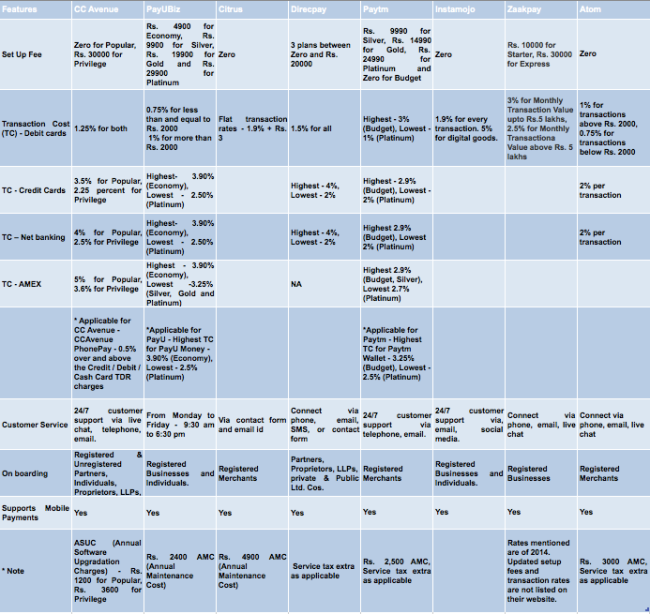

The homegrown IPGs ended up providing everything the big banks didn’t. They started offering world class support, compatibility with third party services and certain providers also have… wait-for-it… ZERO setup fees!

Given below is a comparison of the most popular IPGs in India. (Prices in INR)

Options, options everywhere. Image Credit: IndianOnlineSeller.com

There is a massive void for a good, affordable and secure IPG in Sri Lanka right now. And a homegrown IPG will most probably *not* come under draconian laws like the Exchange Control Act imposed by the Central Bank. The Exchange Control Act, for instance, was formulated in 1985, and unsurprisingly, is very outdated. It prohibits Sri Lankan citizens from opening bank accounts abroad and even investing in foreign securities. And let’s face it, in this day and age of globalisation, a law that prevents the free flow of capital doesn’t make much sense.

To their credit, the Central Bank is slowly relaxing monetary controls, but progress, in this case, seems to be at a snail’s pace, honestly.

2. The regulatory and policy environment needs to improve

Sri Lankan policy makers usually tend to favour the big companies over startups. And this wasn’t much of a problem during the old economy, where mass production was the order of the day and the playing field was tilted in favour of the big boys. You can’t really blame anyone for that, because in the industrial economy, the largest players were also obviously the most visible players. But today, thanks to the magic of the internet, we are entering the “Digital Economy” and the old rules are being broken. A new economy needs a new set of rules for everyone to play by and countries that have noticed this are reaping the rewards. Because ultimately, one of the best things about the proliferation of the internet is that it levels the playing field for everyone.

The 2016 budget actually had a few concessions for VCs and incubators. But what we need are policies that deal with fostering digital trust, data protection, funding and stuff like that. The Turkish Government recently released a policy paper for the Digital Economy and it has a few helpful pointers about what a suitable policy should aim to achieve:

- The need to strengthen multi-stakeholder Internet governance and increase collaboration between different stakeholders

- The necessity of fostering digital trust in an era that has witnessed an explosion in collection and usage of personal data to stimulate innovation

- The challenge of bringing regulation in line with new disruptive business models and complex technologies

- The need to bridge the digital divide to increase the consequent positive socio-economic impact on businesses and citizens

While these are the *two* elephants in the room, it is also equally important to take a long term view when trying to solve these issues, because these aren’t problems which can be fixed overnight. The British Government’s Digital Economy Strategy for the next three years and also former Aussie Communication Minister (and now Prime Minister) Malcolm Turnbull’s policy document for E-Government and the Digital Economy make for an interesting read. Go check them out (you should).

It is time for us to realise that a digital economy and e-commerce can do so much more to improve people’s lives and incomes. Provided we do it right, it can even take our economy to a whole new level.