The disastrous nurdle spill resulting from the May 2021 fire onboard the MV X-PRESS Pearl off the coast of Sri Lanka led to extensive discussions about environment protection — particularly concerning marine and coastal conservation. Unfortunately, the focus has largely been on the specific event and less on the bigger picture — the combined impact of the worsening climate crisis and ineffective resource management on Sri Lanka’s coastline.

Education and awareness about establishing and safeguarding Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and related tools continue to remain low; this comes as no surprise, but must be remedied.

What are MPAs?

MPAs are among the most successful natural resource management tools established to achieve conservation objectives. However, simply designating locations as MPAs is insufficient; issues such as mismanagement, resource extraction and habitat degradation persist. According to Nishan Perera, co-founder of Blue Resource Trust, a conservation research and consultancy organisation, though there are a number of MPAs in the country, only seven are truly functional and lack of education and awareness about the importance of these areas has meant many setbacks.

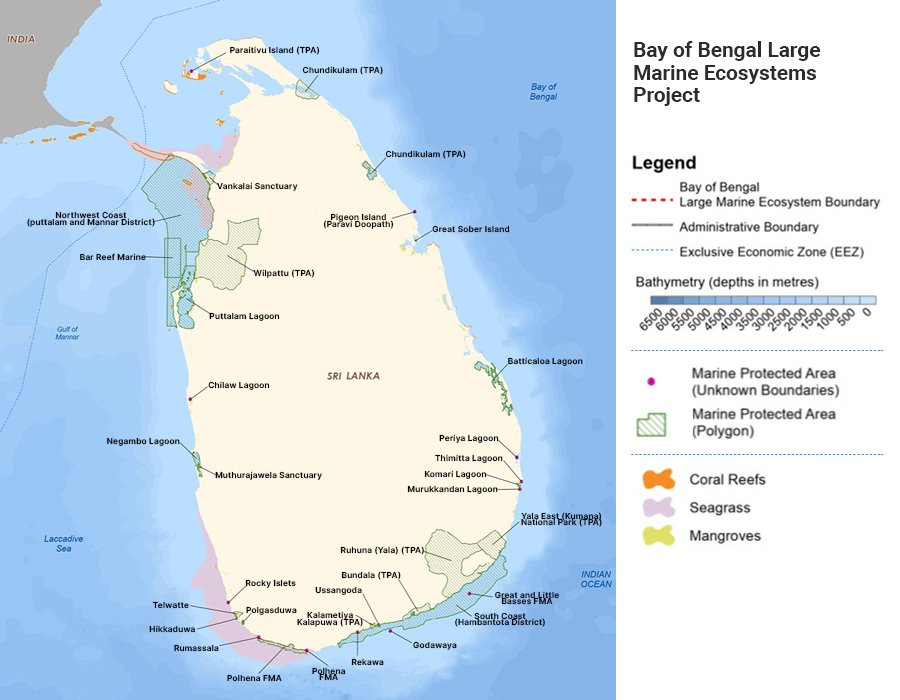

MPAs are established to help shield ecosystems that are threatened by human activities, such as overfishing and oil drilling. In Sri Lanka, MPAs are also established to protect archaeological sites and other historically important places; Ussangoda and Rumassala are examples of this. All MPAs are intended to form ecologically coherent networks and work as an endowment for the long-term effectiveness of conservation and sustainable use of these marine environments.

Perera, told Roar, that while the exact number of MPAs in Sri Lanka vary based on how they are defined, seven were established with the primary purpose of protecting against high tide lines, seagrass meadows, coral reefs, rocky reefs and mangrove fringes. These seven MPAs are Hikkaduwa, Bar Reef in Kalpitiya, Pigeon Island in the east, Rumassala in the south, Adam’s Bridge in the north-west, Kayankerni in the east, and the Great and Little Basses in the south.

‘No-take’ zones, in which the extraction of resources, including fishing, is prohibited is difficult to implement in Sri Lanka given the high population density and fishing intensity in the country, Perera explain, however, he believed, “…it is still important that some critical habitats are declared as ‘no-take zones’ and included within large MPAs, where fishing effort and methods are regulated and tightly controlled.”

On an island rich in a multitude of natural resources, the use of MPAs can help steer resource users toward achieving high levels of sustainability. However, although the major legislation used in declaring protected areas — the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance (FFPO) of 1993 — allows for the establishment MPAs in Sri Lanka, there is a serious lack of implementation, monitoring and management, rendering MPAs largely ineffective. Poor education and awareness in communities is a major contributor to the misuse of natural resources, while a lack of human resources, community involvement and funding also interfere with the establishment and management of successful MPAs.

How Useful Are MPAs?

Establishing a marine protected area can help both marine ecosystems and local communities. For instance, protecting coral reefs and mangrove forests along a coastline can provide healthy habitats for marine life as well as human communities, as they contribute to strengthening the shoreline against erosion.

A study conducted in 2006 found that the direct tidal wave impact from the tsunami in the Indian Ocean in 2004 may have been reduced because of mangrove fringes and coral reefs systems that worked in place as protective barriers against the direct tsunami impact to the shoreline. However, it is important to note the amount of damage caused to reef ecosystems by the 2004 tsunami. Landscape alterations, bleaching and disease rose to 6.7% and caused the coral cover in the Gulf of Mannar to reduce from 48.5 % to 26%.

Successful MPAs can provide sustainability to local economies through responsible fisheries and eco-friendly tourism. Though it may seem at first that implementing this may be challenging, due to ongoing illegal fishing practices in Sri Lanka, the declaration and actual implementation of MPAs could help local communities to subsist in their artisanal fishing for far longer and more sustainably by allowing damaged ecological habitats to heal and thrive in the long term.

According to MPAtlas.org, a curated library of MPA information that tracks progress in implementing marine protection globally, none of Sri Lanka’s MPAs have been designated ‘no-take’ MPAs.

Dr Sarah Hameed, a senior scientist at MPAtlas and Director of Blue Parks, a non-profit oceans conservation organisation based in the USA, told Roar, “Marine protected areas are the best, most efficient tool we have to safeguard marine wildlife from the many impacts of human activities that threaten the ocean. For this reason, Sustainable Development Goal 14 (Life Below Water) included implementing marine protected areas across at least 10% of the ocean by 2020. Most countries did not achieve this goal, but we made more progress in the last decade than ever before. Now we need to continue accelerating the creation of well-managed strongly protected marine areas. We also need to improve the protection in the many MPAs that are not working because they are not well-designed, well-managed or strictly protected enough to conserve marine wildlife.”

What Can We Do?

Perera feels implementation of conservation regulations in Sri Lankan MPAs lack two major aspects: 50% of its failure, he said, is due to a lack of human resources, while the other half is a result of systematic and structural failures in the management process. Perera said authorities needed to look at solutions driven by timely conservation goals and reassess the current management processes to isolate management failures. He added that within an improved management capacity, governing bodies can then develop practical management plans based on scientific information to approach more achievable goals to improve the integrity and quality of current MPAs.

Jagath Gunawardena, a prominent environmental lawyer, also emphasised to Roar that Sri Lanka needs to do more research in order to understand the dynamics of diversity in MPAs to investigate sudden changes that take place in these areas. Once this is done, we can declare knowledge-based interventions to improve quality, he explained.

Coherent MPAs can attract the attention of users to its goals and reestablish ecosystem integrity in the areas — ultimately resulting in increased fish stock and other revenue-yielding opportunities such as artisanal fisheries and aquaculture in local communities. Apart from the economical benefits, well-protected MPAs provide refuge to fish and other marine species to grow and repopulate not only within the MPAs but also in the surrounding waters through a spillover effect.

Governing bodies and stakeholders can also devolve MPA conservation goals to other collaborators within the country — such as nature conservation bodies under their purview — to increase acceptance and awareness of MPAs in the country by local communities. This will lead to goal oriented efforts that are locally generated to eliminate destructive fishing practices and allow better enforcement of regulations to prioritize artisanal fisheries in the areas. A goal oriented MPAs can also provide a common ground for the government and the public to dispense their efforts toward achieving realistic conservation and sustainable goals that will represent the acceptance of futuristic economies and sustainable values in the face of globalisation.