In today’s increasingly congested world, it is difficult to imagine the absence of waste. Waste generation levels are rising — in 2016 alone, the world’s cities produced 2.01 billion tonnes of solid waste. With increasing urbanisation and population growth, annual waste generation is expected to grow by 70% in 2050.

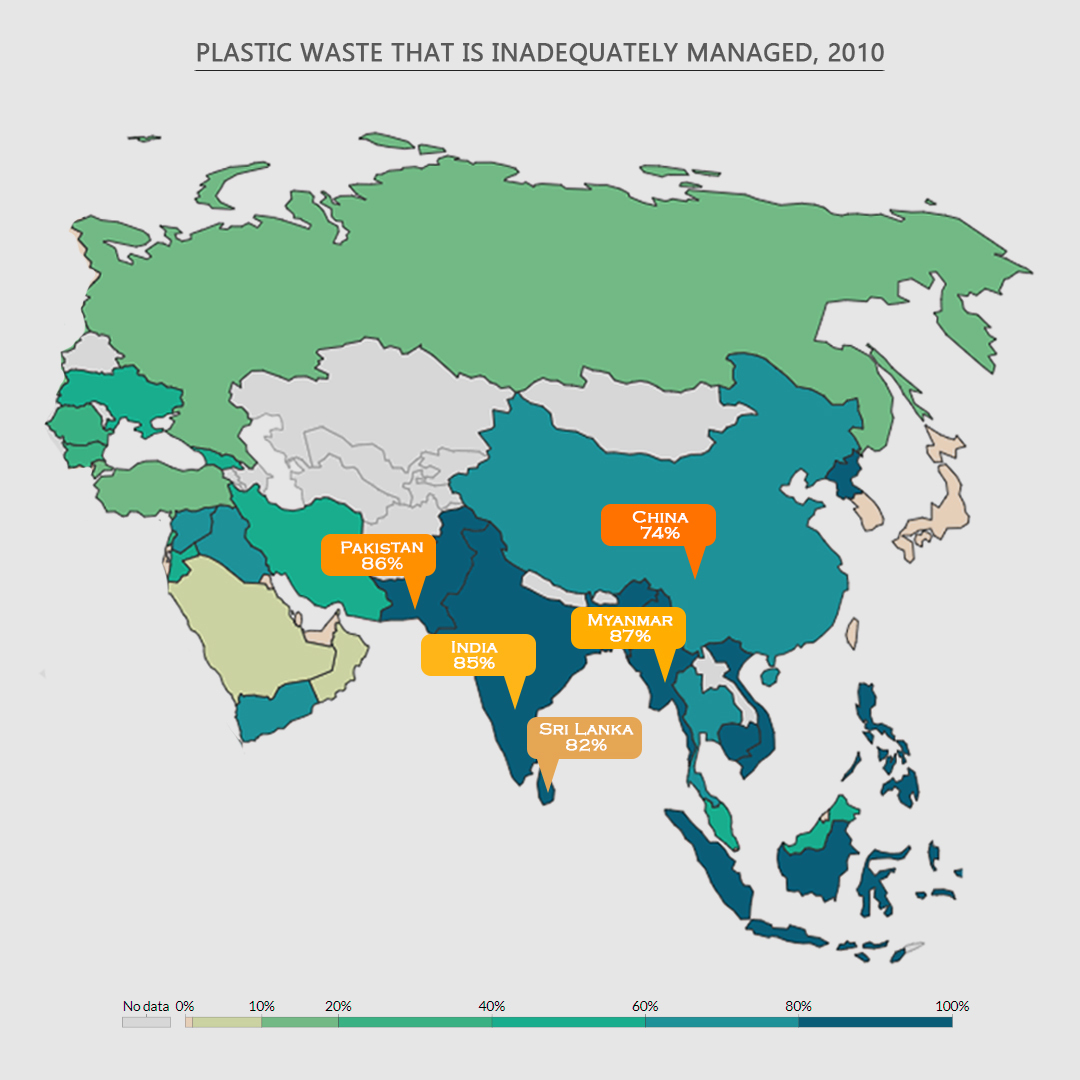

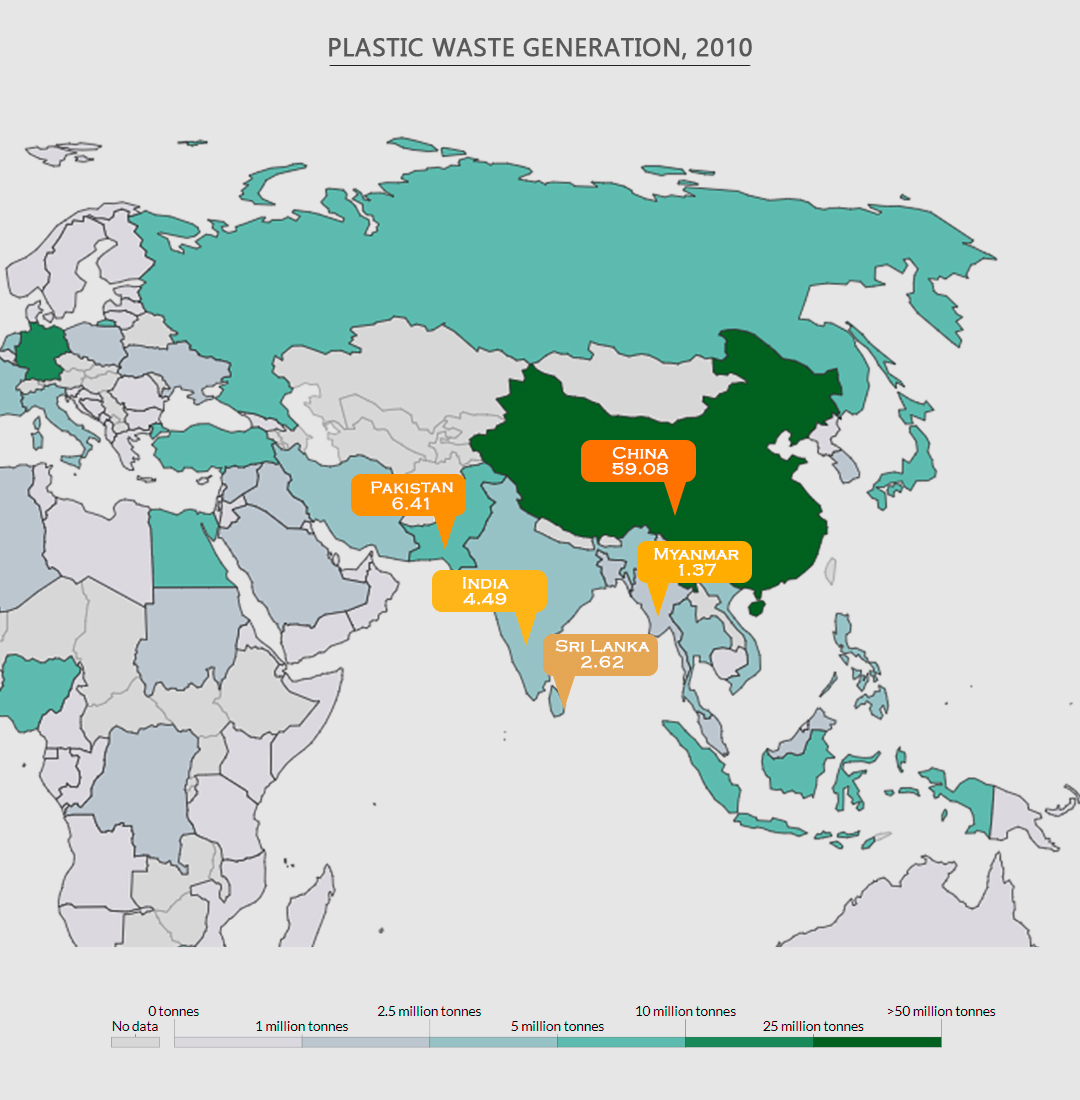

Although richer nations like the U.S.A and Japan produce more waste than countries like Sri Lanka, the problems of waste management are different in the developing world.

Unlike developed nations, we do not have a well-organised means of controlling waste. Garbage is rarely collected on a regular basis, as municipalities are often underfunded. The lack of status and poor salaries associated with the job of garbage collection also creates a system where employees are not trained or able to manage an effective system.

Furthermore, regulations and laws are lax, allowing for polluting practices such as burning trash to be followed frequently.

Over the last few decades, the government has attempted to implement a regulated waste management strategy for the country. However, they were never able to settle on a unified, coherent strategy, and the initiatives that have been taken—such as the Pilisaru Programme—have not been followed through.

So the waste just piles up. It sneaks its way from homes and streets, clogging waterways and piling up in dumps, to the point that it is a hazard to public safety.

Institutional Change

Sri Lanka generates 7000 MT of solid waste per day, with the Western Province accounting for 60% of that statistic. However, only half of that waste is actually collected.

Since the tragedy that occurred in Meethotamulla, the government has been forced to take waste management more seriously.

“Solid waste is a subject matter that comes under the Colombo Municipal Council (CMC) and the Urban Council,” said Jagath Munasinghe, Chairman of the Urban Development Authority (UDA). “After what happened in Meethotamulla, the CMC didn’t have a solution for this for a long time.”

To address this, the Ministry of Megapolis and Western Development—with the involvement of the UDA— is implementing a project to build a large-scale sanitary facility in Aruwakkalu, in the Puttalam district. The landfill began accepting waste from the Puttalam district on March 15. Its scope will expand to Colombo, Dehiwala, and Kolonnawa by the end of the year.

The idea is to transport solid waste from the Colombo district by train to be disposed of at the site in Aruwakkalu, with the promised outcome that the waste will be recycled and deposited without causing environmental damage. But despite this, the project in Aruwakkalu has been met with widespread criticism, particularly from communities living close to the area who have expressed concerns that the project was greenlighted without consulting them.

The environmental impact assessment done by the Ministry of Urban Development, Water Supply and Drainage, acknowledged that the project could pose a significant threat to its surrounding environment.

“That particular area has some of the most ancient fossil trails in the area, as well as massive limestone quarries,”said Shehara De Silva, co-founder of ‘NoKunu’ (No Garbage), a movement to end pollution in Colombo. “The landfill will also attract elephants to the garbage, and if there are no protective measures against this, it could further endanger the species.”

But the project has continued despite these concerns.

It is clear that policy level solutions alone won’t solve the complex problems of Sri Lanka’s inadequate waste management systems.

“In order for government policies to work, we need to put pressure on governments for better solutions to the problem,” said De Silva, “I’m not saying to scrap these projects altogether, but to shift them around. We need policies that take into account the well being of the environment around it. That is unfortunately not happening.”

De Silva believes that incremental change can have a big impact on government policy.

“If every individual does their bit then it will lead to a big change. We can’t expect government policy or even companies to solve this problem for us. We need to put pressure on them to change, that is the only way it can be done,” she said.

PhotoCredit: www.adaderana.lk

Individual Responsibility

While the efficacy of policies continue to prove doubtful, individuals are starting up initiatives to manage waste on their own.

NoKunu is one such movement. Founded by Sumi Moonesinghe, who spent years working in the corporate sector, it has been steadily gaining momentum in Colombo.

The movement has launched many successful campaigns, the most recent one involving the cleaning of the Beira Lake. *But NoKunu is also working on pushing policy in a better direction, with volunteer participation and advocacy programmes.

“The idea behind conducting citizen engagement programmes, is [to] somehow get the government to put some kind of taxation policy on plastic,” said Moonesinghe. “Some kind of additional charge for plastic materials could really deter people from buying it.”

This taxation has already been imposed in many countries, including Kenya, Ireland and Cambodia. In Ireland alone, the taxation of plastic saw a 90% decrease in plastic use.

“A tax on plastic will deter its usage on an industrial level, and that is huge, because industrial waste is the bulk of the problem,” said De Silva.

But while putting their weight behind the waste project, both De Silva and Moonesinghe agree that getting the public to participate in cleaning projects isn’t enough. It is important for private companies to be involved as well.

De Silva also observed that although many people who come to cleanup events seem to do it as a token measure, they eventually become committed to the work.

“Quite a few people do cleanups, but the difference here was that we are literally sweeping through drains, pulling dead rats out of the gutter. We really get into it and it feels long-term,” she said. “When they saw that, and they saw children and young people [participating], we found they stayed and took it more seriously, and asked about ways they could do more.”

As the movement continues to grow, Moonesinghe only hopes that more people in Sri Lanka take responsibility for managing their personal waste.

“Ultimately, consumer pressure will have an impact on companies, and that that will impact the government,” she said. “If we continue to organise, I believe we can get the attention of the government authority. Once that happens, we can really do wonders.”