Last month, a distressing image of shark carcasses on a fisher’s boat said to be in the vicinity of the Pigeon Island Marine National Park, was widely circulated on social media. Public outrage prompted a response from State Minister of Fisheries, Kanchana Wijesekera, who tweeted that officials from the Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources would be investigating allegations of illegal shark fishing in Trincomalee. While results of that investigation have not yet been made public, the shark killing left a trail of questions regarding the protection of shark species in Sri Lanka.

Key Laws And Regulations

Sharks fall into a subclass of cartilaginous fish called Elasmobranchii, which also include rays and skates. These are fish species whose skeletons are made of cartilage instead of bone. Sri Lankan waters are home to 63 shark species, of which several are listed as endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species.

Despite being portrayed in movies and most forms of popular culture as villains who pose a threat to humans, shark attacks — both worldwide and in Sri Lanka — are considerably low; in fact, the number of sharks killed by humans is much higher. Shark fins have long been in high demand for shark fin soup, a delicacy that dates back to the Song Dynasty (960-1279). But the killing of sharks at present goes beyond the need for their fins. The shark meat trade has expanded over time and the meat is consumed both fresh or dried. Other shark products such as cartilage and oil contribute to a market value of a whopping $ 1 billion per year.

While the survival of sharks is threatened by pollution, habitat destruction and rising ocean temperatures, overfishing is the biggest threat on a global scale. An estimated 100 million sharks are killed globally each year by the fishing industry, exacerbating the decline in populations of these top ocean predators.

In Sri Lanka, as per the Shark Fisheries Management Regulations, 2015, issued by the Extraordinary Gazette No. 1938/2, under the Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Act, No. 2 of 1996, five species of sharks enjoy legal protection in the country: the common thresher (Alopias vulpinus), pelagic thresher shark (Alopias pelagicus), bigeye thresher (Alopias superciliosus), oceanic whitetip shark (Carcharhinus longimanus), and whale shark (Rhincodon typus).

The provisions under this gazette stipulate that if any of these sharks are caught, they must be brought ashore with their fins still attached. This curbs the gruesome practice of shark finning, where fins are cut off while the sharks are still alive and they are thrown back into the sea to die a slow and painful death.

Local marine biologists, in the absence of clear photographs, found it difficult to identify the exact species of shark that was seen on the boat in the photo circulating social media but say it could be either bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas) or pigeye sharks (Carcharhinus amboinensis) that are not protected by local laws.

In the event that the carcasses photographed did not belong to the five protected five species, the act of catching and killing these sharks will not constitute a crime. However, if the sharks were killed within the Pigeon Island Marine National Park, then it would amount to a criminal offence — because this particular location is a Marine Protected Area or MPA.

The Role of Marine Protected Areas

The existing MPAs in Sri Lanka are of different types: Marine National Parks, Marine Nature Reserves, Marine Wildlife Sanctuaries (declared by the Fauna and Flora Ordinance), Fisheries Reserves and Managed Fisheries Areas (declared by the Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Act).

Pigeon Island is one of three Marine National Parks, alongside the Hikkaduwa Marine National Park and Adam’s Bridge National Park. With an abundance of marine life and coral cover, the Pigeon Island Marine National Park has gained popularity for recreational activities such as scuba diving and snorkelling.

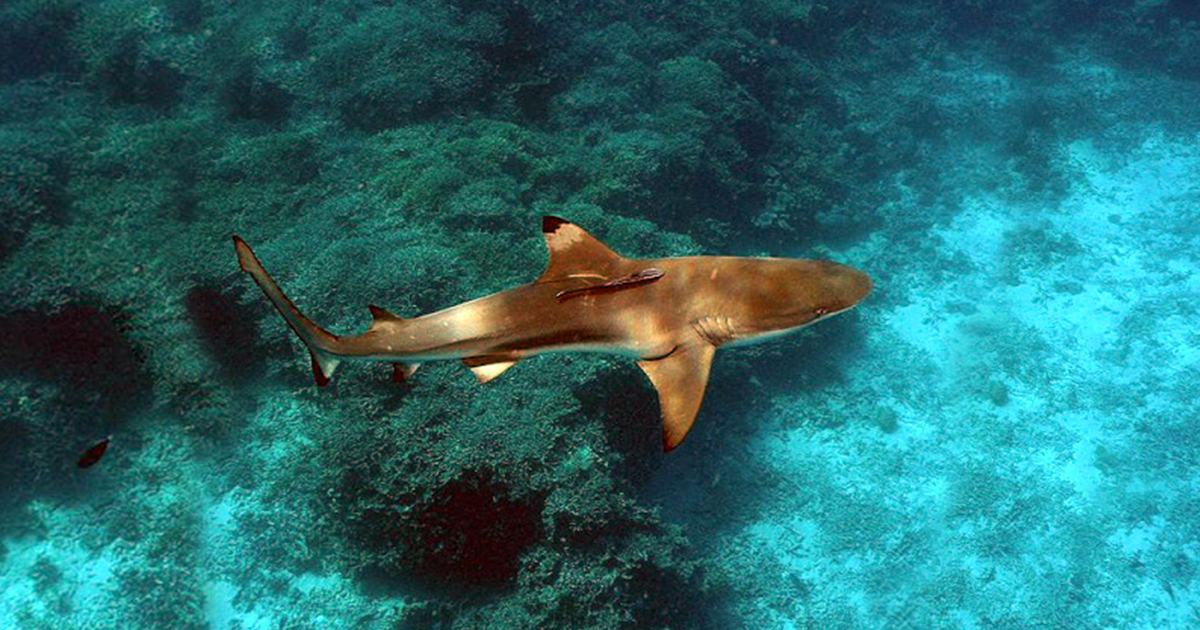

“It is a highly biodiverse Marine National Park with resident shark populations such as the blacktip reef shark (Carcharhinus melanopterus) that are very well known among tourists,” Professor Terney Pradeep Kumara of the Department of Oceanography, University of Ruhuna, told Roar Media.

As per Section 6(1)(a) of the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance (FFPO), it is illegal for anyone to “hunt, shoot, kill, wound or take any wild animal or have in his possession or under his control any wild animal, whether dead or alive or any part of such animal” within an MPA (Marine National Park or Marine Reserve). Hence, if any species of sharks, whether protected or not, were found to have been killed within this MPA boundary, it would amount to a crime in the eyes of the law. Any person who is found guilty of acting in contravention to these provisions will on conviction be liable and subject to the relevant penalties of imprisonment and fines.

“According to information received from tour guides and fishermen based in Trincomalee, shark species such as the blacktip reef shark [which is not a protected species outside of a Marine Protected Area] around the boundary of Pigeon Island are being killed by fishers at night. Once the park closes at about 5:00 p.m., there is no one stationed at the park to observe these activities taking place,” explained Professor Kumara.

Additionally, the act of killing unprotected shark species in the vicinity of an MPA would not amount to a crime unless a gazetted Protected Area (PA) Buffer Zone is in place. PA Buffer Zone is defined by the IUCN as an area between core Protected Areas and the surrounding landscape or seascape which protects the network from potentially damaging external influences and which are essentially transitional areas. Simply put, it serves as a barrier between humanity and a wilderness area, which in this case provides a neutral zone that would further enhance the protection of an MPA.

“Even though a proposed buffer zone was demarcated for Pigeon Island, it has not been gazetted — similar to all other proposed buffer zones in Sri Lanka. The one mile specified in both Sections 3A and 9A of the FFPO is often confused by many as a Protected Area Buffer Zone, when in fact it simply is a ban on development activities that could take place within one mile of the boundaries of a Protected Area. A buffer zone will continue to remain in the proposed status until it is gazetted and concurrently a separate regulatory extraordinary gazette should be issued to provide a regulatory framework on how the Buffer Zone can be sustainably managed, utilised and administered,” said John Wilson, protected area specialist and executive member at Rainforest Protectors of Sri Lanka, a non-profit environmental organization, to Roar Media.

Since it is only alleged that the incident that occurred last month took place in the vicinity of Pigeon Island, and the exact location is still unknown, it is unlikely that what took place would be considered illegal.

Making Waters Safer For Sharks

However, academic experts believe that the killing of these sharks, regardless of whether or not the law recognises it as a criminal offence, is and should be a matter of concern. “These are charismatic species that are being killed and landed in large numbers,” Professor Kumara said. “Attention should be paid to control the killing by taking stringent action against those who violate existing legislative mandates.”

Sri Lanka has a long way to go with regard to protecting sharks, especially considering that only five species of the 63 shark species that glide through our waters are legally protected as of 2015, There is a need to extend legal protection to other species that are vulnerable by adding them to the existing list under the provisions of the Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Act, depending on the research findings available in Sri Lanka while also facilitating further research needed to determine changes in the conservation status of shark species since 2015. The relevant schedule of the FFPO on marine organisms also needs to be amended to reflect the most threatened shark species in Sri Lanka.

“With regards to MPAs — their definitions, types and categories under the provisions of the FFPO need to be updated to serve more unified management and administration,” Wilson added. “Multiple regulatory extraordinary gazettes must also be released determining the size and definitions of Buffer Zones of MPAs. Additionally, to officially add in the newly proposed Sea Mammal Observation Zones, as yet another type of MPA under the FFPO, would provide an additional layer of protection to cetaceans, sea turtles as well as sharks that inhabit deeper waters,” he said.

While the National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Sharks (2018‒2022) specifies measures for the adoption and implementation of shark conservation and management mechanisms, as we are nearing the end of 2021, the plan needs to be updated to extend to at least the year 2030, in order to provide an implementable framework. Along with that, the National Fisheries and Aquaculture Policy (2018) also requires a section dedicated to reflecting the appropriate guidelines for shark conservation and management.

There are more reasons than one for Sri Lanka to start paying serious attention to the protection of sharks; overexploitation of shark populations not only impacts marine ecosystems, but also the marine tourism industry. “Pigeon Island is a tourist hotspot that helps boost the economy with its recreational value,” said Muditha Katuwawala, Coordinator of The Pearl Protectors, a youth-led marine conservation group. Since the fisheries sector too was hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions and the MV X-Press Pearl maritime disaster, fishers have pivoted towards other means of income, Katuwawala explained, adding, “the image we saw recently is a testament to that.”

Sharks are considered a keystone species, which means that their absence would result in an ecosystem dramatically changing or ceasing to exist. “If sharks are no more, all of these recreational activities would fall off as well,” Katuwawala said.

While the struggles faced by local fisherfolk cannot be dismissed, the need to conserve critical shark populations must not be downplayed. Providing alternatives to sustain the livelihoods of these fishers, and educating them on the importance of steering clear of MPAs, would help achieve the goal of providing a haven for sharks to roam our oceans for many more years to come.