When you think about the Sri Lankan highlands, wildlife is not often the first thought that springs to mind. But while this area is most famous for its tea plantations, it is also home to a diverse array of wildlife and a range of important ecosystems.

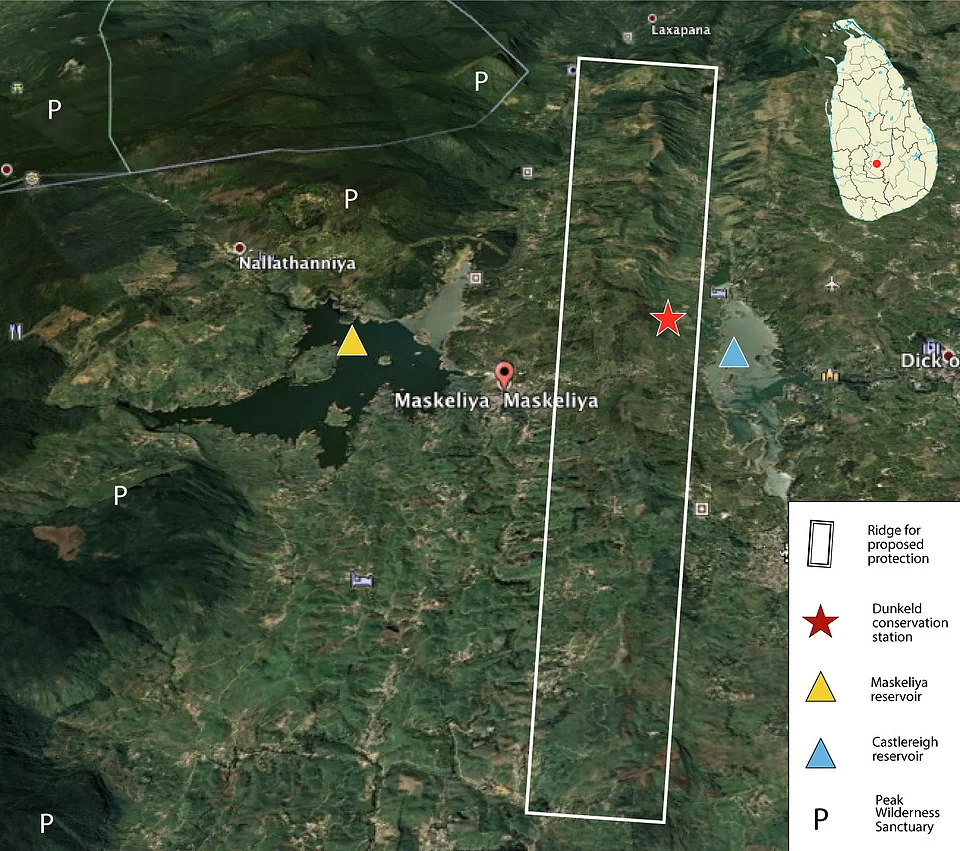

Due to the increased amount of threats both animals and habitats face in the highlands, conservationists and local wildlife authorities have stepped up conservation efforts — one of which is the ‘Peak Ridge Forest Corridor’. A collaborative initiative that aims to support conservation efforts in the highlands, the Peak Ridge Forest Corridor is an 18-kilometre mountain ridge between Castlereagh and Moussakelle reservoirs, adjacent to the Peak Wilderness Sanctuary.

What Is A Wildlife Corridor?

A wildlife corridor is an area that connects habitat areas used by wildlife to avoid humans and connect with each other. These corridors occur mainly in areas where there is a lot of human activity and presence.

In 2016, several leopards fell victim to snares in the area surrounding the Peak Ridge Wilderness. This led to The Wilderness & Wildlife Conservation Trust (WWCT) in Sri Lanka, a leopard-focused research and conservation organisation headed by founding trustee, Anjali Watson and co-founding trustee and lead scientist, Dr Andrew Kittle, to begin researching the leopard population in the area. And what they found was a thriving leopard population.

Panthera pardus kotiya, the leopard subspecies endemic to Sri Lanka, is categorised as threatened, according to the IUCN Red List, and so, the Peak Ridge Corridor aims to protect the leopards that use it, along with the other animals that do too. “Not only does the Corridor provide refuge for the leopard, but it does so for more than twenty-two other mammals and numerous other species that reside here too”, Anjali Watson told Roar Media.

What the Research Revealed

The Corridor, which is the culmination of more than five years of research and conservation efforts to protect Sri Lanka’s leopards, began by setting up remote cameras around the trails, forests and tea estates of the highlands. They discovered that there are two sets of leopard communities that are found on the ridge, one is a residential community of leopards, who have made their home along the ridgelines, and the second a group who appear to be visitors from the adjacent Peak Wilderness Reserve.

Leopards in the tea country are not a new discovery or phenomenon. As Watson tells Roar, ever since tea was first planted in the highlands, planters have been known to tell tales of seeing a leopard at night amongst the tea bushes. “What is novel is that we found that leopards are residing within ‘forest patches’ on the tea estates itself,” she explained. “Before, it was most commonly thought that the leopards were just visitors from nearby forest reserves.”

WWCT’s research found that at least four female leopards, some of who have had multiple litters, live along this lengthy but narrow strip of the Ridge Corridor. There are also five adult males who are, most likely fathers of the cubs. “Andrew is the data cruncher, and this is what reveals their personal stories. It has been amazing to get a glimpse into the lives of these individual leopards over time,” said Watson.

Thirteen estates belonging to five plantation companies have extended support to Watson and Kittle’s efforts to protect and conserve the Corridor — for which they are grateful. She is also grateful for the support extended by the plantation community in backing up a project that protects the territory of the leopards that exist within the tea plantations. “This remarkable change of attitude is what we need to strive to maintain and foster if we are to continue this co-existence and preempt the incidents between leopards and humans that have arisen in the recent few years’’ she says.

Leopards using forest patches and ridges to avoid human settlements is no new phenomenon. “Being strictly nocturnal hunters in the mountains, [leopards] have a ready supply of a wide variety of prey in the wildlife that lives here, and therefore do not depend on livestock and domesticated animals.” she said, adding, ‘we are finding little evidence of dog/domesticated prey as part of their diet, – indicating that the dependency on this is atypical. However, it is often the incident of a leopard taking a dog that gets remembered — and understandably so”.

Female leopards prefer to occupy a smaller area, as this provides a more secure refuge for their cubs. Therefore, the females within the Corridor appear to be permanent residents.“Cubs tend to stay with mothers for up to two years before moving out on their own.” explained Watson, “However, we are seeing that on this landscape perhaps cubs are moving out at an earlier age. Mothers have a habit of sharing and succeeding parts of their territory to daughters,”

Dr Kittle points out that acknowledging the leopard as an umbrella species could be the focal point in rallying support for the conservation of other species, as well as the highly fragile ecology of the region as well. The Central Highlands of Sri Lanka has been recognized as one of two dozen Global Biodiversity Hotspots, as well as a World Heritage Site. One important piece of criteria for maintaining this status is the conservation of the leopard in this highland habitat, that is why the research by WWCT is critical. “Our research not only identifies leopard refuges but also documents the biodiversity within this region.” added Dr Kittle, “ This will continue to ensure the integrity and increase the profile of the highlands. This effort to protect the Peak Ridge Forest Corridor and the surrounding Sanctuaries and Reserves will enhance the preservation of wildlife and ecosystems in this extremely vital watershed.”