An egret snaps its beak at a bottle of Fanta. A farmer mourns the contamination of his rice paddies. A family on the fringes of the Dehiwala canal buckets foul water from their flooded home.

The importance of Colombo’s wetlands—and indeed wetlands in all major cities, globally—cannot be overstated. They are a vital cog in the health and wellbeing of the city’s ecosystem. They are a natural defence against flooding, provide a no-cost sewage network, and grant fertility to the farms and paddy fields that feed the population.

However, they are under threat from the general presumption that they are treacherous and unproductive.

Despite these popular beliefs, Lucy Emerton, Environmental Economist at the UN’s Environmental Management Group, argues that wetlands aren’t a feral breeding ground for mosquitoes and disease.

Rather, they are an essential “natural infrastructure” of the city.

The Consequences Could Be Grave

Since the 1980’s, 60% of Colombo’s wetlands have disappeared through “in-filling and indiscriminate dumping of solid waste”, Dr. N. S. Wijayarathna, Deputy General Manager of Wetland Management of SLLR&DC, told an open table discussion on the preservation of Colombo’s wetlands, hosted by International Water Management Institute (IWMI).

Regardless of this rapid depletion of 1.2% of the wetland zones in a year, Colombo’s water-bearing capacity is still massive: enough to fill 27,000 Olympic sized swimming pools. But should the wetland zones continue to spoil, the flooding implications for a city that is battered by heavy rainfall is potentially devastating.

The government would be wise to learn from the mistakes of Chennai in South India. According to The Guardian:

“Twenty years ago, Chennai had 650 wetlands in and around the city. Today it has 27… In November [2015] cataclysmic floods caused the displacement of 1.8 million people.”

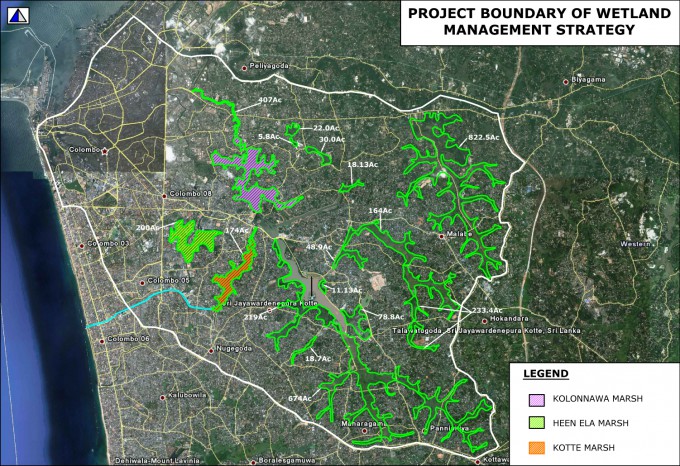

Colombo has a series of interconnected wetlands, referred to as the Colombo Wetland Complex, which includes these wetlands units: Beddagana, Thalawathugoda (Diyasaru Park), Kimbulawela, Madiwela, Kolonnawa, Crow Island, Talangama Tank and Beira Lake. Kolonnawa Marsh, Kotte Marsh, and Heen-Ela Marsh have been identified as the Metro Colombo Urban Wetlands. The complex has a total estimated area of 4,700 acre. Image courtesy Sri Lanka Land Reclamation & Development Corporation (SLLR&DC).

Adding to the decline in Colombo’s wetland is their routine pollution.

Polluted wetlands are less effective at the more discrete operations that they oversee: the reduction of extreme temperatures through evaporative cooling and the improvement of air quality by removing airborne pollutants.

For Dr. Priyanie Amerasinghe, Senior Researcher of Human and Environmental Health at IWMI—and pioneer in the eradication of malaria in the country—wetland pollution has notable implications for public healthcare.

She told Roar Media that the physical dumping of waste and Colombo’s unconnected sewerage system could be a key contributor to last year’s dengue endemic:

“Previously, dengue thrived in contained water, only, but now it may be breeding in foul water, too [i.e. polluted wetlands]” said Dr. Amerasinghe.

“We are uncertain if the disease has mutated, but comparable mutations have occurred in Puerto Rico and Malaysia, and we are researching whether that is the case in Sri Lanka.”

The Economic Value of Wetlands

From above, and particularly to the city’s east, Colombo sparkles with natural open-water lakes, channels, marsh, and swamp; connected by a tapestry of man-made embankments, flooded fields, canals, and waterways.

To the visitor, Colombo’s wetlands present significant biodiversity: 250 species of plants and 280 animals, including myriad birdlife and striking mammals such as the fishing cat and Eurasian otter.

However, professing bountiful biodiversity does not necessarily speak the same language as city planners. Economists talk numbers, spreadsheets, rupees, and dollars.

That said, researcher of Natural Resources Governance (IWMI), Sanjiv de Silva, is surprised the government or private enterprise has not seen the potential economic value of the wetland biodiversity, especially for the tourism sector.

“To actually be able to see a wild cat in a capital city is rather incredible”, he told Roar Media, suggesting that the preservation of Colombo’s wetlands could be achieved by maximising them as a tourist destination.

It certainly feels like the right idea. Think: safari in the city.

Colombo’s pride: the Fishing Cat. Image courtesy Silkwinds.

UN Environmental Economist Lucy Emerton—who categorises herself as different to the classic land-hungry, city planners—is busy proving the economic potential of wetland areas to governments and investors.

Her research in the Ugandan capital of Kampala has had a profound effect on urban development there. In a city where only 50% of the population have access to a sewage system and only 10% of industrial waste is treated, the water purification process naturally performed by the Nakivubo Swamp had an estimated value of $2 million a year. The economic “service” provided by the Nakivubo Swamp led to the reversal of plans to drain and reclaim the wetland.

A good news story, maybe, but it does leave the question: is similar research being conducted in Colombo?

“Sri Lanka is becoming a regional leader in calculating these sort of figures”, explained Emerton.

“Maybe there is a little way to go until people start taking them seriously, but there is some really good evaluation happening”.

Awards Matter

Currently, six wetlands in Sri Lanka are recognised as globally important, the biggest being the Wilputta Wetland Cluster, under the Rasmar Convention (an intergovernmental framework for the conservation of wetlands).

In 2017, Rasmar called for applications for a new award: The Wetland City Accreditation. Colombo has submitted its application, along with seven cities in China, five in South Korea, four in Thailand, two in Tunisia and one in each of Brazil and France. Rasmar expects many more applications, and the results will be released later this year.

The rice paddies around Talangama Tank feed the nation. Image courtesy IWMI.

The accreditation application has breathed new life into the Colombo wetland conservation. IWMI are bringing together the numerous institutions that are affected and who benefit from better wetland management. At the historic Talangama Tank, for instance, the government is learning that the cumulative contribution of the 175 farmers—who cultivate more than 200 acres of land supported by the tank—runs in the millions of dollars.

Similarly, Diyasaru Park, formerly known as Thalawathugoda wetland, has been redeveloped as a place for public recreation; for walking, birdwatching, school trips, and even getting married!

Meaningful projects, such as preserving 60 acres of land close to the city centre to conserve biodiversity and allow easy public access, could be a huge step in Colombo achieving the Rasmar Wetland City Accreditation.

Bodily Functions

When Dr. Wijayarathna proudly proclaimed the wetlands as “the lungs of the city”, his evocative metaphor resounded around the room. But when the truer scope of the wetlands’ importance is considered, the analogy actually does not quite go far enough.

For when wetlands purify our water, they are the city’s kidneys; and when they cool the air, they are its pores.

And when they provide habitat for hundreds of birds or provide a quiet spot for a young couple’s romantic stroll, the wetlands become more than bodily organs: they become the city itself.