Hailed in ancient mythology as the inspiration behind the modern day mermaid myth, the elusive marine mammal known as the dugong has been a source of fascination for centuries among pirates, explorers and colonists alike. Its name, derived from the Malay word dayung, means ‘lady of the sea’, a curiously elegant designation, given the animal’s robust exterior. Yet while watching the dugong melodically glide across the ocean floor, gently cradling its young in its flippers to feed them, it becomes clear why these giant tubes of blubber have come to be mystified in so many cultures as symbols of femininity.

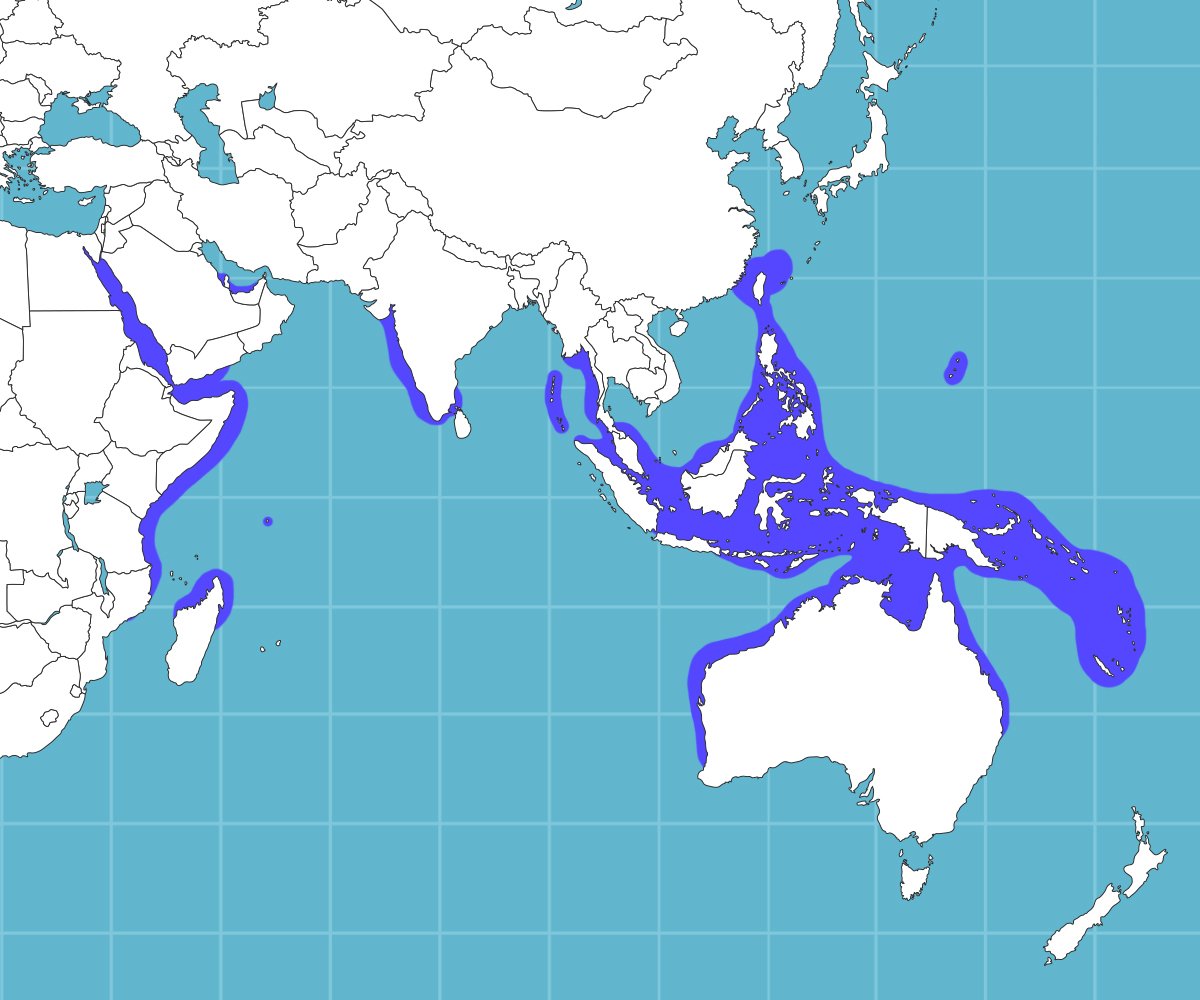

One of four living species of the order sirenia—from which the word siren originates—the reality facing the dugongs today is much less romantic. Usually found in warm coastal waters spanning from East Africa to Vanuatu in the South Pacific Ocean, the dugong has been classified as a globally vulnerable species by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). According to a study done by the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP), the global population of dugongs has decreased by 20% in the last 90 years. They have completely disappeared from the waters of Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mauritius, as well as the western coast of Sri Lanka. In modern day Sri Lanka, dugongs can only be found in the north, along the coast of the Palk Strait and the Gulf of Mannar.

Threats Facing Sri Lanka’s Dugongs

Early scientific fossil studies have shown that dugong presence in our waters dates back to 3,800 BP. According to Dr. Ranil Nanayakkara,a scientist researching dugongs in Sri Lanka,“an excavation site at Jethawanaramaya uncovered a phallic artefact (depicting male genitals), carved out of dugong bone”. This suggests that the dugong could have possibly held some kind of sexual significance in ancient Sri Lanka. Another excavation site in Manthai, an ancient sea port in Mannar, “has unearthed dugong bones with cut marks which show that ancient man, such as the Yakkas, Nagas and Asuras were also feeding on dugong flesh,” said Nanayakkara.

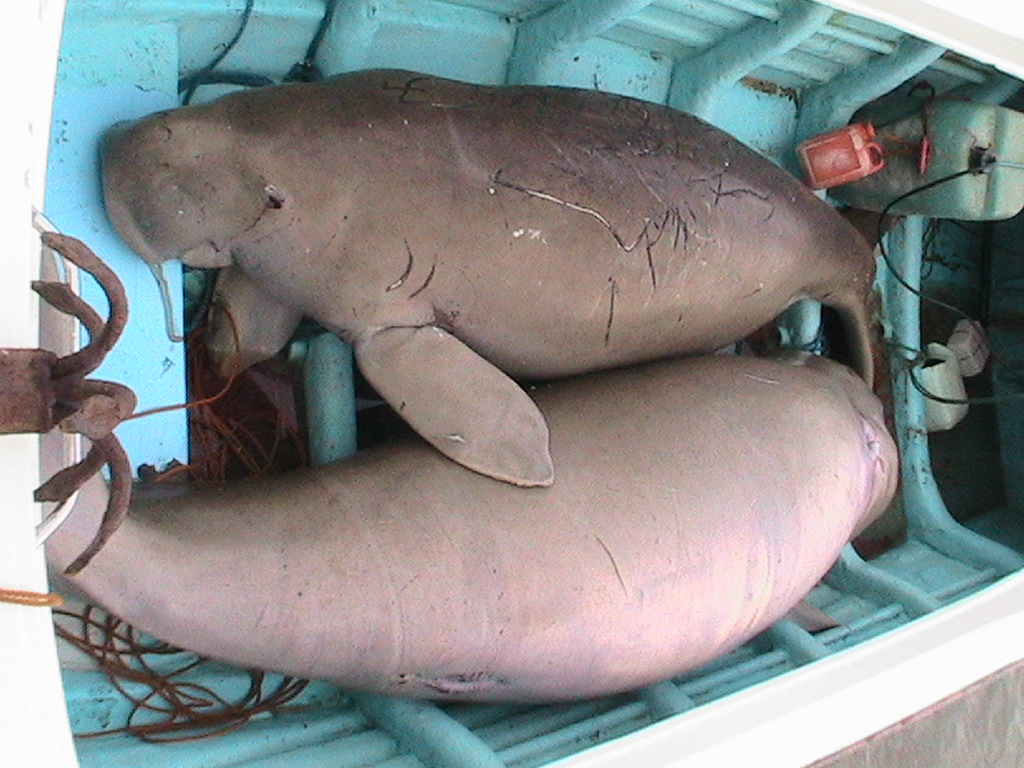

Following an increasing threat to dugongs on a global scale, the Sri Lankan government declared it a protected species in 1970 under the Flora and Fauna Protection Ordinate (FFPO). Despite this, Dr. Nanayakkara stated that “there is still a huge demand for dugong meat, and in the northwestern coasts, there are fishermen who specifically target dugongs. People sell dolphin and turtle flesh saying that is is dugong, so you can see how big the demand actually is.” In a somewhat contradictory statement, Dr Lakshman Peiris of the Department of Wildlife and Conservation stated that although some communities do use these animals for food, it is not deliberate. According to him, only in cases where they are accidentally caught in the nets are they used as fresh food.

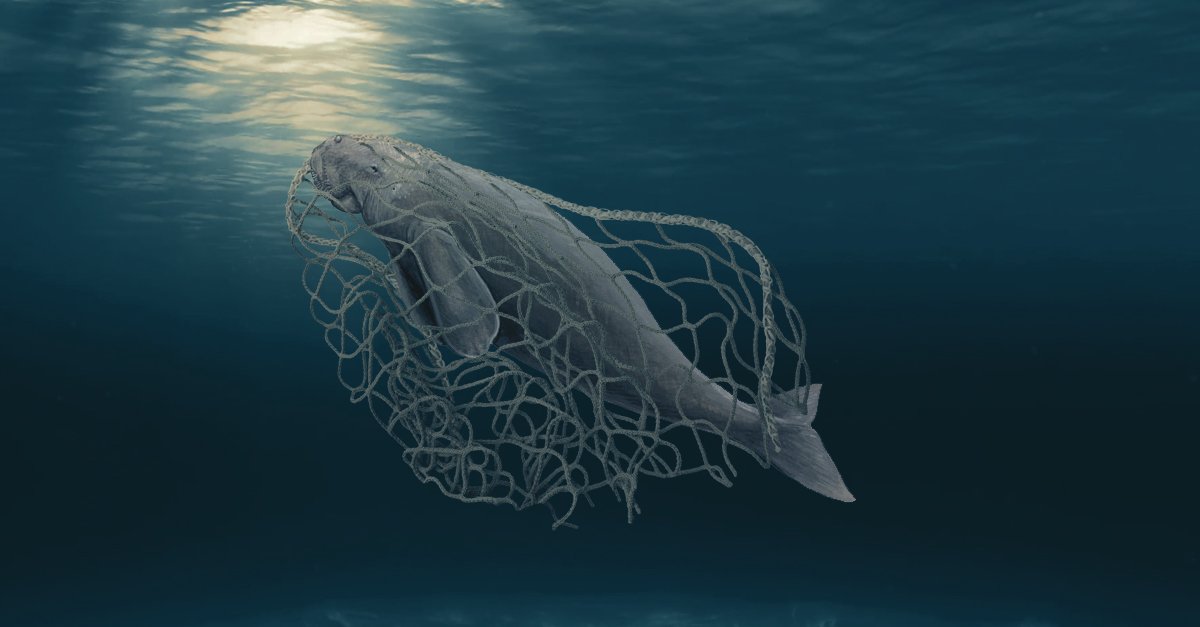

A less contested—and more obvious—threat facing Sri Lankan dugongs today is unsustainable fishing. Being herbivorous mammals that feed primarily on seagrass and other weeds on the surface of shallow waters, these kadal pandi or ‘sea pigs’ as they are known in Tamil, frequently get tangled up in gillnets, and as a result, suffocate to death. Gillnetting involves constructing vertical panels of netting set in a straight line, usually in areas where dugongs feed.

Another, more insidious fishing practice that threatens the dugong is illegal blast fishing. From cultural surveys Dr. Nanayakkara has carried out with the Biodiversity Education and Research team (BEAR), he found that “when dugongs and other animals of value are spotted out at sea, due to modern technology, someone is immediately contacted and sent to whatever location, and dynamite is used to kill the targeted animal.” This practice is primarily directed at securing the valuable meat. It also wreaks immense collateral damage to the environment, as the dynamite kills everything within a certain radius of the animal.

Dugongs meet this same fate in areas where bottom trawling serves as the primary method of fishing. Though declared illegal in July 2017, “there are certain areas in Mannar where is it practiced unhindered,” says Nanayakkara. “It is difficult to say why this is, there are a lot of people with political influence and so on who are doing this without any problem at all. Many of the fishermen aren’t historically from these areas, due to relocations that happened during the war,” he observed. Bottom trawling has a detrimental effect on the seagrass beds, which in the long term affects dugongs as it is their main source of food.

Resolving these issues in Sri Lanka is proving to be a slippery slope, one that researchers, conservationists and scientists alike are treading with caution. But conservation without scientific knowledge has its pitfalls. As Dr. Nanayakkara admits, “the study of marine organisms and ecosystems on a global scale is still in its infancy.” Given this, how do we go about conserving something we have only scratched the surface in understanding?

An Uncertain Ocean

“Though we are an island nation, our people haven’t really been going out to sea and carrying out research,” says Nanayakkara. “It is ironic, but what I’ve noticed in my work here and abroad, is that in the majority of these island nations, its inhabitants don’t really have much interaction with the sea, perhaps due to fear.” The incredible vastness of the ocean also makes scientific research around it very expensive, and calls for a large amount of funding for these projects to be greenlighted. It may seem like a startling statistic, but historically, only three people in the world have managed to venture into the deepest part of the Marianas Trench, compared to the 536 that have been to space. Developing nations such as Sri Lanka simply do not have the kind of economy required to support such research.

In the case of the Sri Lankan dugong, no comprehensive surveys have been conducted on their populations in the last three decades. During the time of the civil war, the entire northern part of Sri Lanka was inaccessible to researchers, and international entry into the country was limited. Much of the research conducted on our mermaids of Mannar has been gathered only in the past nine years. Despite this, several organisations, such as the Dugong And Seagrass Conservation Project, as well as the Biodiversity Education and Research group have been gaining ground (and acquiring funding) to conduct more research on the dugong, and also formulate sustainable fishing practises which could help with their conservation.

A Sustainable Future

Given the fact that modern scientific study on dugongs is still nascent, as well as the imminent threat of fishing to the species, the future of the dugong in our waters looks bleak. It is unrealistic to call for an end to gillnet fishing in the north, considering how integral this practice is to the local economy. In the case of bottom trawling and blast fishing, it has been proven that criminalisation of these practices often serves to drive them underground. Taking these realities into consideration, how do we formulate a sustainability model that will work long term?

“It is important to engage local communities in our conservation efforts. We are dealing with a huge area of the sea, which is very difficult to patrol by the government or police, so community participation is a must,” said Dr. Pieris. He has been working on an initiative in partnership with the Department of Wildlife Conservation to galvanise local communities in the north to spearhead dugong conservation efforts.

When visiting areas around the Gulf of Mannar, Dr. Pieris and his team realised that the majority of youth engage in fishing as their main source of income. They decided to provide them with alternative nets that reduce risk to larger mammals such as the dugong, but the fishermen discovered that these nets yielded much less fish. To compensate for their loss of income, the Department identified alternative income sources by supplying sewing machines for garment making, and connecting community members with a clientele base to buy their products. These efforts have been made in selected villages, and Dr. Peiris found that the majority of residents have been receptive to these changes, as long as their wellbeing was taken into account as well.

The team also found that community youth were very keen to work as tourist guides.

To help them with this, the team provided them with English lessons, allowing locals to capitalise on the the tourist market and use it for their own economic growth. When asked about the possibility that encouraging tourism for economic growth could counteract the efforts made to protect the dugong, Dr. Pieris underscored the importance of developing tourism sustainably. “It is important to impose limitations on the kind of tourism that we practice,” he said. “We need to make sure to cater to tourism in a very controlled way that benefits both the environment and the communities that live in it.”

We are entering a wobbly time with regards to the future of our environment, perhaps as wobbly as these mysterious mammals themselves. While growing research and conservation efforts may shift the tides in favour of the dugong, their presence in our physical world is one that is littered with uncertainty.