In the recent past, Sri Lanka’s economy suffered several setbacks due to two major events: a terrorist attack and a pandemic. After the tragic Easter Sunday terror attacks, the country began slowly picking up the pieces. From January to September 2019, the economy managed to grow 2.6%, a sharp decline from the 3.3% recorded within the same period in 2018.

Sri Lanka recorded a 2.7% growth rate for the financial year 2018/2019 (ended June 2019), which the World Bank highlighted as being one of the poorest performances in South Asia. Though the IMF forecast that the economy would rebound to 3.5% in 2020 early this year, the COVID-19 pandemic has made it difficult for local sectors, such as agriculture, apparel and informal SMEs, to make a comeback. The burden remains largest on the tourism sector, which has already endured blows this year with tourists cancelling trips to the country in droves due to heightened restrictions on travel.

What steps can the economy take to mitigate the impacts arising from these two worst-case scenarios?

The answer is not simple, but for national-level efforts to succeed, they need to be backed by resilience at a local level. For this, we must shift the focus to Sri Lanka’s Local Government authorities and work towards strengthening the financial resilience of the subnational Government.

Role Of Local Government Authorities

Under the devolved tier of the Central Government are the provincial councils and local authorities of Sri Lanka. The local authorities are made up of Municipal Councils, Urban Councils, and Pradeshiya Sabhas. At the end of 2017, there were a total of 341 local authorities, comprising 24 Municipal Councils, 41 Urban Councils, and 276 Pradeshiya Sabhas.

The local authorities are the most accessible representatives of the Government of Sri Lanka, working closer to the ground, in proximity to the people in their respective areas. They are required by definition to respond to the needs of people in terms of delivering better services and ensuring their quality of life remains high and their concerns resolved.

In addition to this, local authorities also play an important facilitatory role in terms of local enterprise creation. According to the World Bank’s Doing Business Index, three out of the 10 critical indicators that impact a country’s business environment fall under the domain of local authorities; namely, setting up a business, construction permits, and property registration.

The local authorities receive funding from the Central Government, but they also have other means of raising revenue, such as from the collection of taxes and rent. They rely on government grants and ‘Own Revenue’ in order to provide services to the public.

Local Government expenditure is split between ‘recurrent expenses’ and ‘capital expenses’, with services like maintenance work (of libraries, cemeteries, etc.) falling under ‘recurrent’ and building new roads and bridges falling under ‘capital’.

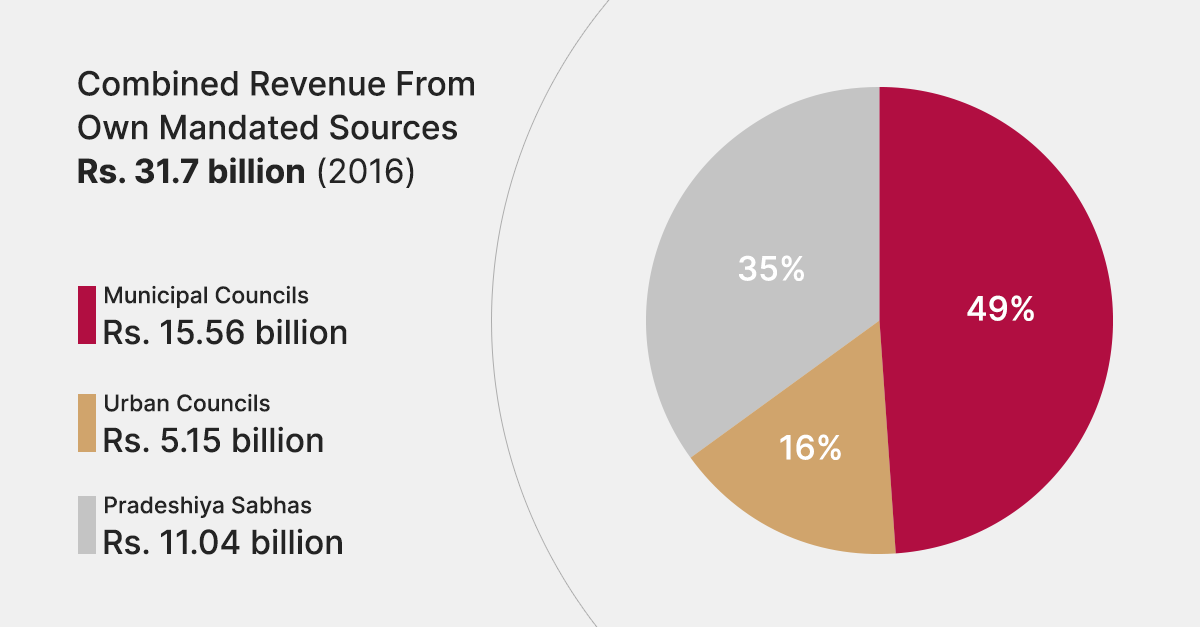

The local authorities received a total of Rs. 30.8 billion as government grants in 2016 (according to the latest data available), and a combined revenue of Rs. 31.7 billion from their own mandated sources. Of this, Municipal Councils accounted for Rs. 15.56 billion (49%), Urban Councils Rs. 5.15 billion (16%), and Pradeshiya Sabhas Rs. 11.04 billion (35%). Harnessing this potential and channelising that to productive local investments is a potential pathway to strengthen resilience and aid resurgence.

In July 2019, Sri Lanka was elevated to the status of Upper Middle Income Country, in line with the World Bank’s classification terms. The upgrade came 21 years after Sri Lanka’s elevation to Lower Middle Income status, a 50-year slow crawl since Independence that resulted in the country putting its resources to maximum use in order to compete in the cheap labour market and establish itself as one of the top exporters of garments in the world.

This was subsequently overturned in 2020, as the World Bank downgraded Sri Lanka to its previous status of ‘Lower Middle Income’. Regardless, if Sri Lanka hopes to reinstate its Upper Middle Income status, the kinks that come with the label need to be acknowledged.

For starters, as an Upper Middle Income country, Sri Lanka would receive fewer foreign aid grants and less government transfers. In addition to this, we will no longer be ‘compatible’ with the cheap labour market, meaning we would no longer be able to compete with the new ‘Lower Middle Income’ countries and their relatively lower average wages in terms of mass production of consumer goods or services.

Such were the views of former Central Bank Deputy Governor Dr. W.A. Wijewardena, who highlighted the theory of the ‘Middle-income Trap’, in which countries fail to move on from their upper middle income status to become a rich country due to various hindrances.

To be a ‘rich country’, a country has to attain a per capita Gross National Income of USD 12,086, which means the country must maintain a stable growth rate of minimum 9% a year—a formidable task for Sri Lanka, given all its been through so far.

From a long-term economic development perspective, the role and importance of Local Governments is bound to increase, especially in light of the fact that Sri Lanka is on the cusp of an economic upgrade. Though the approach to ensuring economic growth demands holistic strategies spanning various sectors, the need to acknowledge the Local Government’s role in promoting economic development is high. The local authorities hold a trove of economic potential, having generated about Rs. 31.7 billion in Own Revenue (2016).

What is more interesting is that the funds generated from their ‘Own Sources’ were higher than the Central Government’s allocation for the local authorities (aggregate).

The Local Government, by its very existence, is an assurance for a more stable and secure environment for local economic development. This means that the services they provide—from establishing infrastructure like roads, to managing waste, ICT, handling public health, education, and more—need to be performed without delay or discord, in line with the needs of the people.

The local authorities have also evolved beyond their base functions, now implementing development programmes, focusing on empowering women, and various other initiatives targeting the upliftment of the average citizen’s lives.

Due to the accessibility of the local authorities, they are in the best position to ensure that the communities across the country actively participate in deciding which strategic visions must be implemented in order to further development in Sri Lanka.

Post-COVID Economic Recovery

Industries everywhere are facing uncertainty as the most dire pandemic in recent memory takes over the world. In a time when essential service sectors, such as health, food, and transportation, need the most financial backing, governments are finding it difficult to keep the engines running.

Revenue shortfalls have been experienced by all business, social and economic sectors. From cutting human costs to shutting down entire departments, industrial entities are doing whatever they can to stay afloat, but this has also proven to be insufficient for numerous businesses that have had to shut down for good.

In his policy statement, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa emphasised that for successful economic development, Sri Lanka needs to support the upliftment of local communities and carefully prioritise resources. In a press release, he further emphasised the importance of prioritising locally produced goods, strengthening food security, and increasing Sri Lanka’s export income for post-COVID-19 economic recovery. Considering these strategies, how can the Local Government clear a path towards successful recovery?

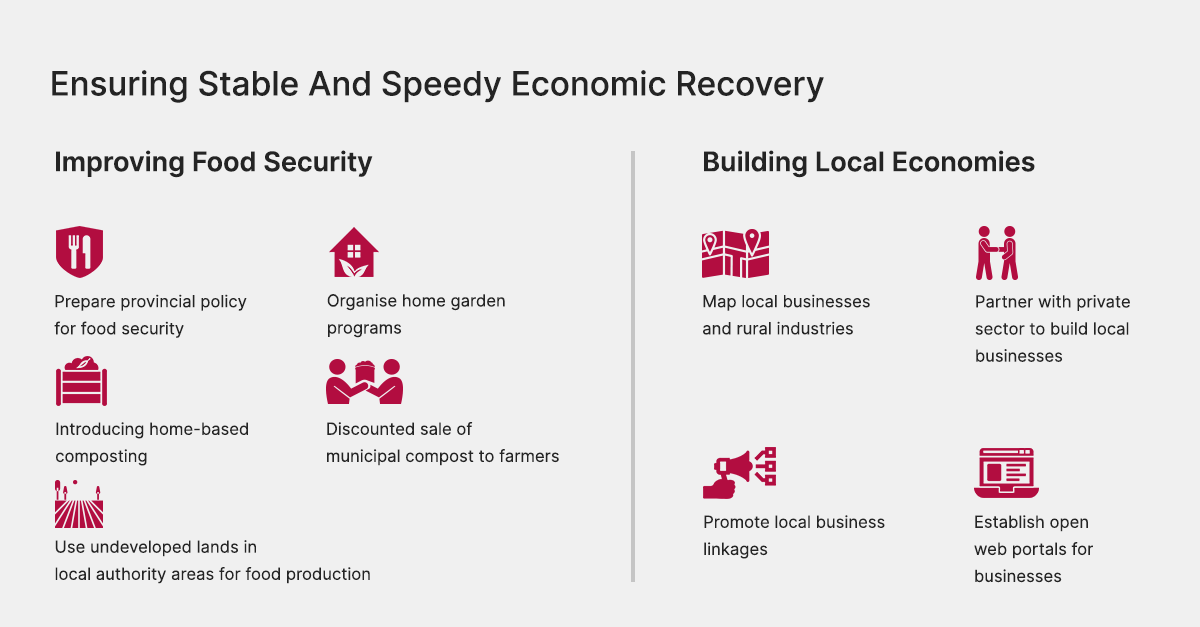

According to a rapid assessment on the impact of COVID-19 on Local Governments conducted by The Asia Foundation in April 2020, there are a number of focus areas to which the Local Government can contribute to in the short to medium term to ensure a more stable and speedy economic recovery. They fall under two major categories, as follows.

- Improving Food Security: This includes preparing a provincial policy for food security; organising home garden programs; introducing home-based composting, discounted sale of municipal compost to farmers; using undeveloped lands in the local authority area for food production; and partnerships with the private sector for using local authority lands for agricultural purposes.

- Building Local Economies: This includes the mapping of local businesses and rural industries; partnerships with the private sector for building local businesses; promoting local business linkages; and establishing open web portals for businesses.

In addition, testing and leveraging new technologies for implementation in local authority ongoing projects could be beneficial. One of the positives that has arisen out of this pandemic is that more and more entities across the board are testing out a range of technologies in order to ease the difficulties posed by COVID-19.

COVID-19 has led to a massive spike in unemployment around the world. This also rings true in Sri Lanka, despite the actual impact of the virus being significantly lighter on our communities than in other countries. One way local authorities could support furloughed or unemployed individuals is by putting forth community-centred upskilling initiatives.

With smaller businesses having to shut down due to rising costs and falling profits, revamping underutilised locations within the local authorities’ respective jurisdictions for the purpose of corporate space is an option, especially for the benefit of MSMEs that are struggling to conduct their businesses without retail space.

Estimating tax income shortfalls due to the pandemic and re-evaluating budgets is crucial in this time period; and pushing to redirect funding to key projects that can be delivered quickly is another step local authorities can take to support the communities that rely on them.

With Sri Lanka’s status being downgraded once again and the COVID-19 pandemic’s heavy effects on various sectors still being felt, it is now more pertinent than ever for the local authorities to become stable and financially independent (and not as reliant on Central Government funding).

This means citizens need to be active and participate in how and what activities are carried out by the Local Government, ensuring that necessary measures are taken to maintain the stability of all local authorities.

In terms of financial power (according to research conducted by the Asia Foundation), local authorities in urban areas are at an advantage, especially due to the denser populace, and therefore have more room to invest in infrastructure and other services for the betterment of the residents of these areas. With the new Government focusing on urban-led development, it is more likely that these local authorities’ financial resilience will be ensured.

As citizens, it is our civic duty to pay taxes. But just as it is our duty, it is also our right to be able to hold the local authorities that we fund accountable. Many Sri Lankans are unaware of how their tax money is spent, in particular, why the Local Government is so heavily dependent on taxes.

By understanding how and why our taxes are spent and engaging with the local authorities relevant to us, we can optimise the delivery of public services—including better infrastructure—and in conjunction, pave the way for a better environment where economic prosperity would be ensured.

Responsive and innovative Local Governments, and responsible and proactive citizens are key for a strong, inclusive and prosperous Sri Lanka.

.jpg?w=600)

.jpg?w=600)