In February 2019, UN Women collaborated with the Ministry of Women and Child Affairs, and the Korean Embassy in Sri Lanka to produce Sri Lanka’s first report examining the Government’s policies, budgets, and plans, and how they affect women with disabilities in particular.

The report, titled ‘Women with Disabilities and Their Access to Economic Opportunities: Through the Lens of Gender Budgets’, conducted a study involving 400 persons with disabilities across four districts, and the difficulties they face in entering the workforce as well as remaining in it.

The study is also the first in Sri Lanka to use a gender budgeting framework to examine government plans, policies, and budgets as well as its impact on women with disabilities.

It revealed that women with disabilities face intersecting biases, supported by gender and disability stereotypes, meaning they encounter multiple barriers when accessing economic opportunities.

Situational analysis

One billion people around the globe live with disabilities, accounting for 15% of the world’s total population. Within the community, one in five women have disabilities, with the prevalence rate being 19.2% amongst women as opposed to 12% amongst men.

This holds true in Sri Lanka as well, as stated in the 2012 National Census, as the number of women with disabilities outnumber men across all age groups. Yet they still only comprise 15% of the employed persons with disabilities in the country.

This disproportionate representation within the workforce, as the study goes on to reveal, is a key indicator of inherent biases within the system that prevent women with disabilities from obtaining the same opportunities as abled women, or even men with disabilities.

Disability rights and National Action Plan

According to UN Women, in recent years, “there has been greater recognition by the (Sri Lankan) Government to commit resources for inclusive development”.

The first step was taken by the Government in March 2007, when Sri Lanka signed the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD); this was later ratified in February 2016.

An initial report was released with a detailed account of how Sri Lanka went about implementing the CRPD, including relevant policy, legal, and institutional measures adopted by the country.

Constitutional guarantees are now in place for the non-discrimination of persons with disabilities, assuring “respect, dignity and individual autonomy”, which, upon the ratification of the CRPD in 2016, further strengthened the rights of persons with disabilities.

In 2014, the Government put forward a National Action Plan for Disability to address this disconnect. The plan was meant to promote and protect the rights of people with disabilities. It was to set in motion initiatives that would provide the disabled community with equal opportunities to access both education and employment. The Government views this as a stepping stone towards fully including people with disabilities in society, while they contribute to national development through their knowledge, experiences and skills.

The plan focuses on seven key areas, namely: empowerment; health and rehabilitation; education; work and employment; mainstreaming and enabling environments; data and research; and social institutional cohesion.

To realise this plan, the Government allocated Rs. 65 billion in its Medium Term Budgetary Framework (2014-2016), which was done post-Cabinet approval of the proposal.

But despite this, certain obstacles remained, in particular, that of assimilating women with disabilities into the workforce. This is where gender budgeting comes in.

What is gender budgeting?

According to Stotsky (2016), gender budgeting is “an approach to budgeting that can improve it, when fiscal policies and administrative procedures are structured to address gender inequality”.

In order to combat the discrepancy between the number of men and women employed across the workforce, policymakers had to redefine the parameters within which they approached the matter.

Advertising campaigns and raising awareness about inequality was not enough to mobilise women into joining the workforce, particularly in fields like STEM. Despite inherent biases stacked against women, small policy alterations, they noticed, could do wonders to improve the work climate in which women worked. Through gender budgeting, the key kinks in the system can be identified and eliminated.

One such issue that incorporating gender-based perspectives aids to eliminate is ensuring equal distribution of resources and funds. Through identifying the different needs of women vs. men, so as to determine resource distribution in an equal manner, it enables evidence-based decision-making in public funds allocation.

But policy isn’t the only sphere within which gender budgeting is pertinent. Employers have a lot to benefit too.

For example, it could help greatly improve progress and output across the board, as targets, objectives and processes have now been optimised to work in favour of all members within workspace.

GRB as a framework

In 2002, the Republic of Korea became one of the first Asian countries to initiate gender-responsive budgeting (GRB). This tied in with the Incheon Strategy, introduced in 2012, which targets accessibility for and inclusion of people with disabilities.

The strategy was the first set of “regionally agreed disability-inclusive development goals for Asia and the Pacific”, made possible with the aid of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific.

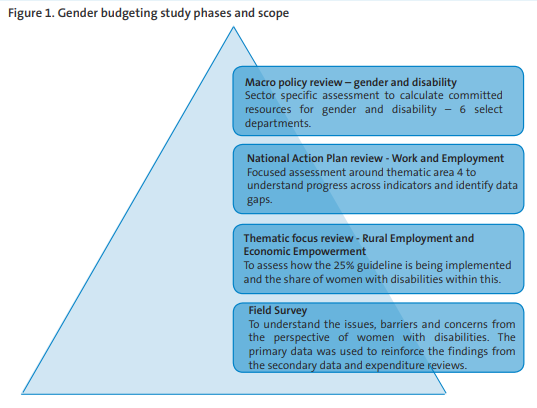

Which is why the ‘Women with Disabilities and Their Access to Economic Opportunities’ report is doubly important. Taking South Korea’s preceding strides as the guide, the report—the first of its kind in the country—uses GRB to examine public policies and budgetary gaps from a gender and disability perspective, most importantly, in terms of employment and economic opportunities.

In 2016, the Sri Lankan Cabinet mandated the allocation of “at least 25% of project investment on economic development of rural women”.

Following this, in 2018, a Budget Call Circular requested “mainstreaming of gender budgeting and disability rights in the preparation of national budget estimates”.

GRB has, over the recent years, proven to be effective for “gender mainstreaming within government policies and budgetary priorities”, states UN Women in the report.

GRB has been incorporated in over 90 countries worldwide, and 65 among them are supported by UN Women. Up to 29 countries in the Asia-Pacific region have begun implementing GRB. Though it was initially introduced in Australia in the mid-1980s, GRB as a strategy has gained acceptance slowly but steadily over the past several years.

Providing solutions

Rather than viewing it as a separate budget targeting women, GRB is an assurance that the allocation of public resources is effectively carried out to empower women. In order to provide adequate solutions to a rising problem, in-depth analyses are carried out.

As policies and legislation need to be sufficiently amended to improve women’s rights, incorporating gender-based perspectives can help benefit all people, and in particular, the more marginalised groups within society.

Take biases against disabilities and gender, for example. Through ensuring that sufficient provisions are made to ensure non-discrimination in both education and employment, as well as empowerment of women entrepreneurs, it is possible to mobilise a large segment of Sri Lanka’s population. Through GRB analyses, both policy and legislation can articulate better defences against such discrimination.

Through the introduction and implementation of gender-responsive budgeting, it is possible to improve the progress trajectory Sri Lanka is on, leading to greater transparency, an empowered populace, resilient economy, and better rights for all citizens.