With Sri Lanka’s Parliament dissolved, there is a debate raging on the legality of drawing funds from the Consolidated Fund to pay for key public expenses. Chapter XVII of Sri Lanka’s Constitution specifies that Parliament must oversee Sri Lanka’s public finances. However, the extraordinary situation Sri Lanka found itself in when it was forced to postpone scheduled Parliamentary elections to deal with the unexpected COVID19 pandemic has resulted in the Consolidated Fund being used without constitutionally mandated Parliamentary oversight. While the debate remains unresolved, we thought we’ll write a quick explainer on what the Consolidated Fund is.

Basically, The Government’s Purse

The Constitution of Sri Lanka sets out the basis for the Consolidated Fund. Article 149, Chapter XVII, explicitly states, ‘(1) The funds of the Republic not allocated by law to specific purposes shall form one Consolidated Fund into which shall be paid the produce of all taxes, imposts, rates and duties and all other revenues and receipts of the Republic not allocated to specific purposes’ and ‘(2) The interest on the public debt, sinking fund payments, the costs, charges and expenses incidental to the collection, management and receipt of the Consolidated Fund and such other expenditure as Parliament may determine shall be charged on the Consolidated Fund.’

What this means in simple terms is that the Consolidated Fund is the place all of the government’s income goes to and out of which all its expenses are paid. In essence, it is the government’s purse.

How Does The Consolidated Fund Work?

Article 150 of Chapter XVII specifies that for funds to be withdrawn under normal circumstances (i.e., when there is a functioning parliament) the Minister of Finance must first issue a ‘warrant’ (a signed, written order that specifies an amount to be disbursed) to that effect.

However, the Parliament must approve any expense that is to be incurred during the financial year by passing a resolution to that effect. Usually, this means approving the Appropriation Bill for the year i.e. the Budget. It is important to note that the warrant is only valid if Parliamentary approval is granted.

If Parliament is dissolved before the Appropriation Bill for the financial year has been approved, the President can authorise money to be issued from the Consolidated Fund to pay for expenses such as salaries and pensions. This is allowed only until the expiry of a period of three months from the date on which the new Parliament is summoned to meet.

In special cases, the President can also authorise funds from the Consolidated Fund for election expenses—but only in consultation with the Commissioner of Elections, once the Elections Commission has specified how much from the Fund will be needed to hold an election.

Who Puts Money Into The Consolidated Fund?

All government revenues from taxes, imposts, rates and duties flow into the Consolidated Fund. So in essence, it is the tax-paying public that funds the Consolidated Fund.

Can The Consolidated Fund Run Out Of…Funds?

It is always possible that the Consolidated Fund’s inflows can be inadequate to cover its outflows. There are several ways this can happen. For instance, rapidly increasing debt repayments can quickly render government income from taxes insufficient. Indiscriminate subsidies which are a popular election tactic, can saddle the state with a considerable annual bill. Alternatively, a country could have a very small number of taxpayers, and an overwhelmingly large number of people who depend on welfare handouts. Any scenario of this nature will bring about a mismatch between income and expenditure.

Think of a joint account held by a married couple into which they direct their salaries and withdraw money to pay for expenses. Now, assume that the couple’s household expenses are far greater than their income. In order to make up for the shortfall, the couple may decide to transfer some expenses to a credit card, thus taking on a little bit of debt. In a similar manner, if the government’s income is insufficient to meet its expenses, the government must decide how it is going to make up for the shortfall in income—and very often, this means taking on debt.

How Much Money Does The Consolidated Fund Actually Have Right Now?

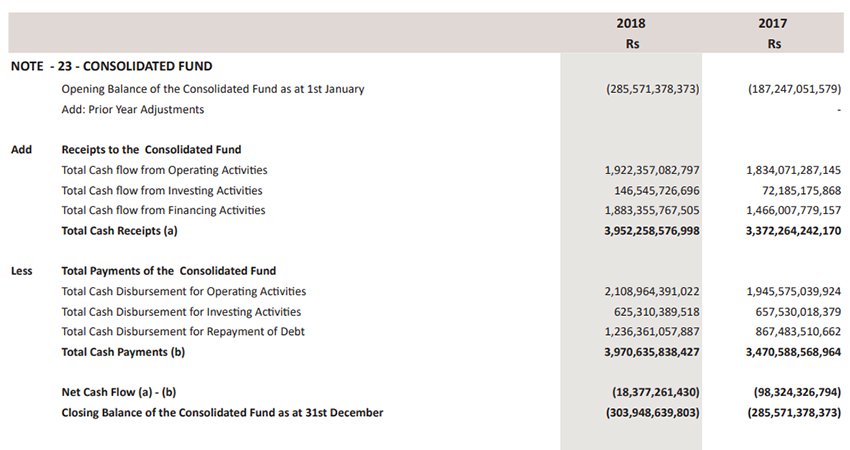

According to the 2018 Annual Report of the Ministry of Finance (the most recent report publicly available at the time of writing), the Consolidated Fund is overdrawn by almost LKR 304 billion.

Why?

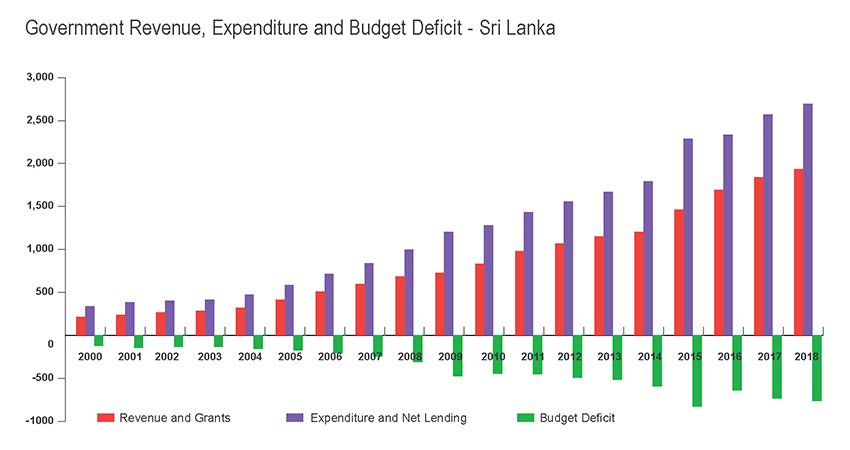

Dr. W. A. Wijewardene, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, explained this succinctly: “Since the Sri Lanka Government has been running deficit budgets throughout, the monies it gets by way of normal operations of the Government are insufficient to meet its normal operational expenses. The gap has to be filled by making a net borrowing—that is, borrowing more than the Government’s debt repayment liabilities. Since these borrowings do not take place at the required levels, the Fund is always overdrawn. What this means is that the Government has incurred some of the expenses in its books but since it does not have sufficient amount of cash, it is indebted to the nation by the overdrawn amount.”

He added, “Here is an important observation that can be made about the Government’s cash indebtedness to the nation. The overdrawn amount has been increasing over the years along with the increase in the budget deficit. For instance, as at the end of 2016, the overdrawn amount was Rs. 187 billion. This has increased to Rs. 286 billion at end-2017 and further to Rs. 304 billion at end-2018.”

But How Can Funds Still Be Issued If The Consolidated Fund Is Overdrawn?

There are a few ways and means in which funds can be diverted to the Consolidated Fund. One of the more recognisable methods, as explained earlier, is to borrow—from the markets (either domestic or international) or the Central Bank itself. [There are other methods, of course but we shall leave them for another, longer, article.] As with everything, that course of action also has its own long list of pros and cons, the bottom line being that if not done prudently, it could have disastrous implications on the economy. Public finance is often a balancing act and governments must be cognisant of their actions and implications on the wider economy.