Sri Lanka’s most romantic export commodity is probably cinnamon – that is, “true” cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum), earlier known as Ceylon cinnamon, (Cinnamomum zeylanicum). Mentioned in the erotic Biblical Song of Solomon (it allegedly fragranced the garments of Abishag the Shunemmite), besides being touted as an arouser of amorous ardour, the enigma of its origins added to its mystique.

Some historians think that the Ancient Egyptians knew it; they may have used it to mummify corpses, from around 1300 BC, the time of the 19th Dynasty ‒ the line of which King Rameses II was the most famous member. Queen Hatshepsut sent an expedition to Punt, which returned with the marvels of that country:

“…all goodly fragrant woods of God’s-Land, heaps of myrrh resin, with fresh myrrh trees, with ebony and pure ivory, with green gold of Emu, with cinnamon wood, khesyt wood, with two kinds of incense, eye-cosmetics, with apes, monkeys, dogs, and with skins of the southern panther, with natives and their children.”

However, ti-sps, the ancient word thought to have stood for “cinnamon”, may, in fact, have been used for East African camphor; the constituents of the roots of both being similar.

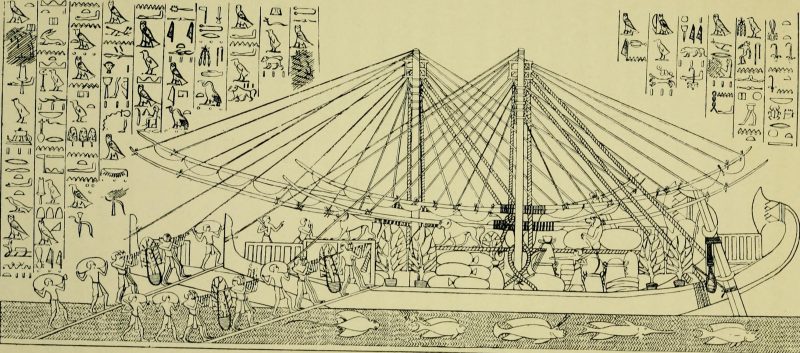

Hatshepsut’s ships returned from Punt loaded with marvels. Image courtesy wikimedia.org

Biblical Spice

The Bible appears to confirm that cinnamon was known among the people of the Middle East at that time. According to the book of Exodus, God instructed Moses to make an oil for anointing the priests:

“Take thou also unto thee principal spices, of pure myrrh five hundred shekels, and of sweet cinnamon half so much, even two hundred and fifty shekels, and of sweet calamus two hundred and fifty shekels, And of cassia five hundred shekels, after the shekel of the sanctuary, and of oil olive an hin: And thou shalt make it an oil of holy ointment, an ointment compound after the art of the apothecary: it shall be an holy anointing oil.”

Cinnamon is also mentioned among the proverbs ascribed to Solomon. Moses was dated to around the same time as the 19th Dynasty, and Solomon to the 10th century BC. However, modern scholarship suggests that the books of the Bible were compiled much later than supposed, probably in the 8th-6th centuries BC. They may have been subject to editorial contamination during the exile of the Judaean elite in Babylon. So we cannot be sure whether the cinnamon trade existed before the 6th century.

Æthiopia

In classical times, the source of cinnamon was unknown to its occidental consumers. According to the ancient Greek historian Herodotus, the Arabs:

“… say that large birds carry those dried sticks which we have learnt from the Phoenicians to call cinnamon… to nests which are made of clay and stuck on to precipitous sides of mountains, which man can find no means of scaling… they divide up the limbs of the oxen and asses that die and of their other beasts of burden, into pieces as large as convenient, and convey them to these places, and when they have laid them down not far from the nests, they withdraw to a distance from them: and the birds fly down and carry the limbs of the beasts of burden off to their nests; and these are not able to bear them, but break down and fall to the earth; and the men come up to them and collect the cinnamon.”

Similar legends about the source of the spice occurred throughout history. The 1st century Roman writer Pliny the Elder repeated this story, with some scepticism, adding that the Phoenix was said to be the main bird to collect cinnamon twigs, and that arrows loaded with lead were used to bring down the nests. However doubtful, he nevertheless reiterated this fable in his section on birds, saying that the Arabian bird was the “cinnamologus”, which we know to be entirely fabulous. This story continued to be copied until the 13th century.

Regarding the source of cinnamon, Herodotus said “where it grows and what land produces it they are not able to tell, except only that some say (and it is a probable account) that it grows in those regions where Dionysos was brought up.”

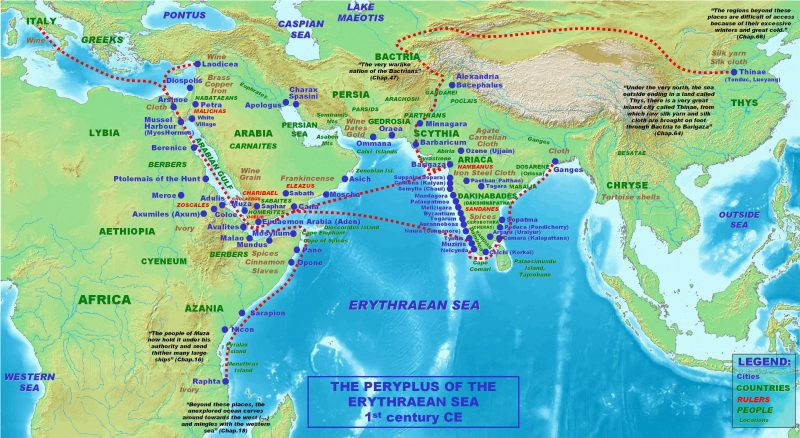

According to the Greek myths, Dionysus was reared in India. Pliny thought it came from “Æthiopia” which, in the Hellenistic cosmology, stretched along the south of the Indian ocean.The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a rutter (navigational handbook) from the early first millennium, knew nothing of cinnamon in India, but mentions the Horn of Africa as being the source of cinnamon.

The Indian Ocean according to the Periplus. Image courtesy columbia.edu

Eden

Jean, Lord de Joinville, who served with King Louis IX of France in the Seventh Crusade (1248-54), heard that the Nile flowed into Egypt from Eden. He learnt that the dry wood of plants such as cinnamon, ginger, aloe, and rhubarb, which grew on the Earthly Paradise, were blown down by the wind into the Nile, and washed downriver; being captured with nets by men experienced in the task, before the river entered Egypt.

This fantastic description may receive an unlikely confirmation in a different context. Ibn Battuta described how mountain torrents washed cinnamon wood down to the Puttalam shore, where it lay in “great heaps”, to be gathered by merchants. The Arabs believed that Sri Lanka was close to Eden, and the true circumstances of cinnamon collection may simply have been transferred to the Nile, which, according to certain interpretations, was one of the four rivers of Paradise.

It was not until the late 12th century, that the Persian scientist and geographer Zakarīyā ibn Muhammad al-Qazwīnī identified Sri Lanka as the source. And not until the Italian Franciscan missionary Giovanni da Montecorvino wrote home in 1306 about his travels in South Asia and China did Europeans discover that the source of cinnamon was an “island which is hard-by Maabar”.

It appears that the traders deliberately hid the source of the valuable spice. Pliny thought they did so in order to keep the price elevated. Certainly, Robert Knox observed that it grew in abundance in Sri Lanka and was hence not greatly esteemed by the inhabitants. Ibn Battuta commented that South Indian merchants transported it, at the mere cost of the gift of a few clothes to the King. The purposeful obfuscation of the trade in the spice has made the task of unravelling its circumstances all the more difficult.

Philological Evidence

The philology of cinnamon may offer some evidence. The Oxford English Dictionary says that the English word “cinnamon” derives, via the Greek Kinnamomon or Kinnamon, from an (unspecified) Phoenician word, related to the Hebrew qinnamon.

The 17th century Dutch traveller Johan Nieuhof said that the “The Portugueses call this wild Cinnamon [growing in South India] Canella del Mato, i.e. Wood Cinnamon, the Malabars Larva and Bahena, as also Kau-nema, i.e. Sweet Wood, from the word Kau, which in their Language signifies Wood, and Nema, i.e. Sweet, the Malayans Kau Manis, the Zingalese or inhabitants of Ceylon Kurudo or Kurundo, the Arabians Querfaa, and Querfe as also Kerfak.”

The Portuguese canella derives from the Latin canna, meaning “tubiform”, from the shape of the rolls of dried bark; similar terms were used widely in Europe: in England, canel was used before the classics-derived cinnamon came into vogue. So there are no clues there.

Some authorities suggest that the Malay kau manis is the root of kinnamon. They think that, because of the lack of reference to Sri Lanka as the source of cinnamon, it is unlikely that the island exported cinnamon in antiquity, and they consider Malaya as the more likely source. More than one theory holds that what was referred to as “cinnamon” was actually cassia – it could have been Chinese cinnamon (Cinnamomum cassia), Saigon cinnamon (Cinnamomum loureirii) or Batavia cassia,Cinnamomum burmannii).

Indonesians

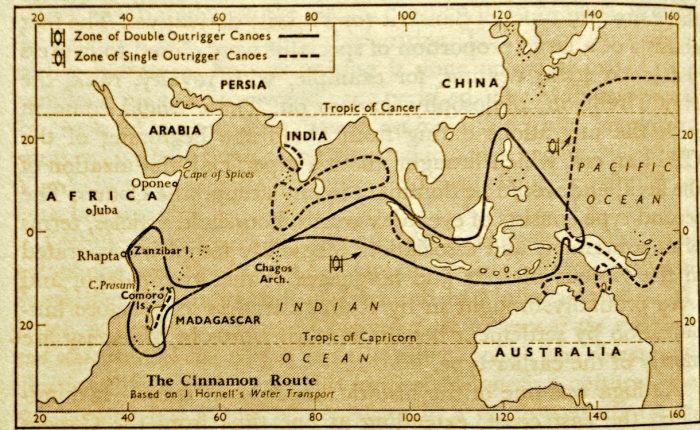

According to one such theory, Indonesian traders exchanged cloves for Chinese cinnamon – called Gui in Chinese, from which the Malay kau manis is derived. They took this across the Indian Ocean to “Rhapta”, on the East African coast, for transport overland and by sea to the Horn of Africa.

In support of this theory, Pliny said the “Troglodytes” bought cinnamon from the Æthiopians, and carried it in rafts, which were driven by the winds to “Ocilia” (an anchorage on the Red Sea coast of Yemen, not far from modern Mocha). Rafts were known in East Asia and Indonesia. It is known that Indonesian people settled in Madagascar. So it is possible that Pliny was talking about Indonesians.

However, the Periplus mentions the use of rafts by traders of southern Arabia, so Pliny’s Troglodytes need not have been Indonesian. Pliny also said that the Troglodytes’ rafts were non-steerable, lacking oars or sails, so that “… it is almost five years before the merchants are able to effect their return, while many perish on the voyage.” This makes his story less likely!

On the other hand, double-outrigger boats, resembling the Sri Lankan oruwa, but with an extra outrigger, are known on both sides of the Indian Ocean – around the Malaysian-Indonesian archipelago as well as in the seas around Madagascar and off the Tanzanian coast.

Outrigger boats may show Indonesian migration and trade patterns. Map from The Spice Trade of the Roman Empire by J. Innes Miller

The migration to Madagascar began around the 4th century, which is later than Pliny or the Periplus. However, Indonesian traders could have been plying those waters earlier. Nevertheless, it seems to rule out their role in the cinnamon trade in the Egyptian period, if not later.

Philologically, too, there are objections. The Hebrew terms for cassia, kiddah and ketzioth, distinct from qinnamon, are derived from the Ancient Egyptian kdy kdt, which occurs in the context of Punt. The Judaeans were unlikely to have confused them.

Yonas

From about 2500 BC, Omani Magan boats plied the coasts of the Arabian Sea. Indo-Aryan speaking migrants probably arrived in similar craft in Sri Lanka about the 6th century BC. Around this time, we have the earliest Biblical mentions of cinnamon and also the first appearance of the Brahmi script, in Sri Lanka and South India. Brahmi appears to have its roots in the Aramaic script, widely used in the Middle East from about the 9th century BC.

Replica of Magan boat at National Museum of Oman. Image courtesy wikimedia.org

This does suggest that there was a Middle-Eastern connection. In the 4th century BC, King Pandukabhaya reserved part of Anuradhapura for Yona traders – the term means “Greeks”, but it was probably an anachronism, possibly being a catch-all for “West Asian” (modern Sinhala Yonaka means “Moor”).

These Yonas may have been southern Arabian Omani or Sabaean merchants, who may have carried cinnamon to the ports of Arabia and the Horn of Africa. Pliny mentions that the monsoon winds carry ships from Ocilia direct to Muzirus (Muciri) on the Kerala coast, and the Periplus identifies several ports in the area which exported pepper.

The Bible mentions that the Queen of Sheba arrived in Jerusalem with “camels that bare spices, and very much gold, and precious stones.” While probably “an anachronistic seventh-century set piece meant to legitimise the participation of Judah in the lucrative Arabian trade,” together with Assyrian inscriptions, it indicates that Saba (which had queens until the 7th century BC) was a major commercial power, trading in spices.

Tintoretto’s painting depicting the Queen of Sheba bringing Solomon gifts (c. 1545). Image courtesy wikimedia.org

The Arabic querfaa must have come from karuvaa, used in both Malayalam and Tamil for cinnamon, and in turn probably derived from the Sinhala kurundu. So the Arabs must have got cinnamon through “Malabar” intermediaries, as Ibn Battuta indicates.

Greeks and Romans displaced Sabaeans in the Indian maritime trade after about 100 BC. Archaeologists unearthed a great many Roman artifacts in the Pattanam dig site in Kerala, which was probably Muziris, dated to 100 BC-500 AD. After that, the Arabians seem to have taken over from the Romans. So querfaa may be more modern than the (probably Sabaean) term from which qinnamon originated.

The cinnamon plant. Image courtesy writer

Today, the South Indian term kau-nema should probably be rendered as kaa-nama. Indo-Lankan anthropologist Mowshimkka Renganathan says that the similar-sounding archaic Malayalam term kaananam (and the related archaic Tamil term kaanagam, which is used in the same context) means “woods” or “thick forest cover”. In Sinhala, kurunda (as in the place name “Katukurunda”) means about the same. Is it possible that a Malayali adjective for “wild cinnamon” was transported to the Middle East as the label for true cinnamon?

There are too many gaps in our knowledge, and reasonable doubt remains. Until evidence of cinnamon is definitely uncovered at a port of antiquity, theories concerning commerce in the spice will remain conjectural. The mystery surrounding cinnamon will remain.

Featured image courtesy divehiholdings.com