Colombo’s food landscape has significantly diversified over the last decade. The average Colombo resident today has a much wider range of cuisines to choose from, and there is practically a new restaurant on every street. One of the segments that is experiencing rapid growth is fast food.

The first international fast food chain to open in Sri Lanka was Pizza Hut, in 1993. This novelty outlet located on Union Place, became instantly popular among middle income families, particularly due to its elaborate play area. It also offered the kind of food that was not easily available in Colombo at that time. Since then, many more fast food chains that have ventured into Sri Lanka have met with similar, widespread success. For instance, at the opening of Subway on Duplication Road, queues extended out onto the road. Other chains have also received similar hype.

The fast food industry’s reputation in its country of origin, however, is very different. In the U.S.A, an average Taco Bell experience consists of curt interactions with overworked customer service agents and cheap, potentially dangerous food. The franchise’s history has been littered with controversy. In 2011, the company was sued for falsely advertising its “taco meat filling” as ground beef, when in reality the filling did not meet the legal requirements to be labelled as such. It is accepted in American public opinion that Taco Bell outlets(and other fast food chains) serve unhealthy, fabricated food aimed primarily at low income segments. They are also widely blamed as being one of the chief culprits behind the country’s obesity epidemic.

In sharp contrast, Taco Bell outlets in Sri Lanka boast amicable, modern interiors, hip wall murals and even a doorman positioned at the entrance of the building. A regular meal can cost up to Rs 1,000, and single sides and desserts are priced as high as Rs. 500. The dining experience is an upscale one, especially for a fast food chain. We visited one of their outlets and asked the manager what their target customer base is, and whom they intend to attract with their marketing. Her response was that “…only high standard people come to eat at Taco Bell.” It is interesting that what is seen as a cheap food source, targeting the lower income bracket in the U.S.A, is marketed to middle income and affluent sections of society in Sri Lanka.

An Urbanising Nation

In most developing nations, urbanisation is one of the main factors that influences a shift in dietary patterns. Urban environments offer access to more white collar jobs, which in turn allow people to view food as more than just a necessity. As income rises, there is a growing desire for a varied diet and better quality food, making non-staples more important.

According to a study on food consumption patterns in Sri Lanka, the percentage of total income spent on food in rural areas is 25-30%, and rice-based foods are consumed much more than wheat-based products. However, in urban areas, the percentage of income expenditure on food is between 60-75%. Furthermore, wheat-based consumption here is much higher compared to rural areas. Those with higher income levels in more urban areas are the most likely to seek out Western fast food. This is particularly because it is priced at a higher rate, and usually more easily available in urban areas.

Where these multinational chains choose to locate themselves also serves as a driving factor that influences which market they will appeal to the most. In the States, fast food chains— particularly McDonald’s and Taco Bell—are found everywhere. In poorer areas, people sometimes have much easier access to fast food than they do to grocery stores. However, the opposite is true in Sri Lanka, where most people have access to markets selling fresh produce. But fast food chains are found primarily in bigger towns and cities, particularly in industrialised areas.

According to an economist who wished to remain anonymous, fast food chains are usually established in bigger towns and cities in developing countries. She said that rigid eating patterns and low spending potential in rural areas means it makes little logistical sense to market multinational fast food companies in such areas.

“These [urban] areas are where they can actually turn a profit in these parts of the world, as this is where the demand lies,”she stated. “Because the income gap in Sri Lanka is much wider than in the West, if these companies were to target their products to lower income groups, they wouldn’t be able to turn a profit.”

Ravi Rathnasabapathy, an economist and resident fellow at Advocata, also echoed this view. “Most of these fast food companies have to import a good percentage of their ingredients. Considering how expensive imports are in Sri Lanka, it makes sense they can’t sell a burger for the same price as a [rice] packet,” he said.“While breads and cheeses are regular staple foods in Western countries, they are expensive to obtain here.”.

The Big Mac Index

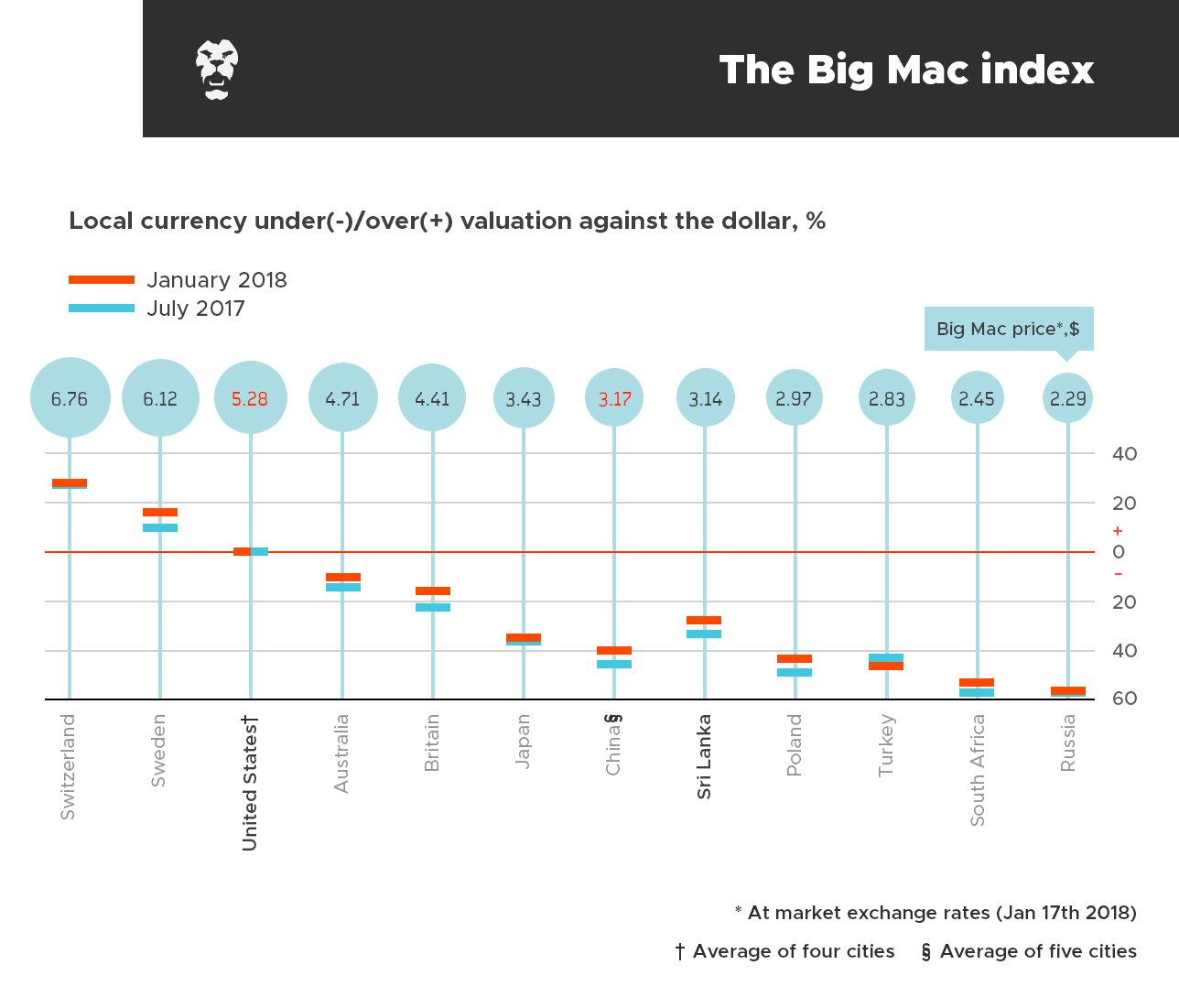

The idea of using fast food as a tool to inspect a country’s economy is not new. In 1986, The Economist came up with the Big Mac Index, a guide used to measure the purchasing power parity between countries, by using the price of a Big Mac as the measure.

“Purchasing power parity is a theory suggesting that if two currencies were to be at par with each other, the value of the same product must be equal in each country,” explained Rathnasabapathy. By comparing the price of a Big Mac in different countries, the Big Mac Index can determine the value of that country’s currency in terms of its purchasing power.

According to the Big Mac Index, a Big Mac in Sri Lanka costs Rs. 550, and $ 5.50 in the U.S.A. This implies that the value of Rs. 550 in U.S dollars, based on Big Mac prices alone, should be $ 5.50. The actual dollar value of the Rs. 550, however is $3.14. The difference between the exchange rate implied by the cost of the Big Mac, and the actual exchange rate of the two countries suggests that the Sri Lankan rupee is 33% undervalued. This basically means that the value of the Sri Lankan rupee is lower than it should be. What you can buy in Sri Lanka for a certain amount of money, you would not be able to afford in the States, if you were to convert that same amount of money to dollars.

This index serves as a useful tool to help situate a country in a larger economic context, but it does not account for the differences in the quality of goods between countries. Although the comparative price of a Big Mac between America and Sri Lanka is a useful tool that can tell us a lot about Sri Lanka economically, the runaway success of fast food chains here can also provide an astute social and cultural understanding of our country.

Marketing To The Middle

The marketing of multinational companies has had a significant impact on the global psyche. The first McDonald’s outlet to open in Asia was in Tokyo, Japan in 1971, facilitated by a wealthy Japanese entrepreneur called Den Fujita. Fujita’s marketing strategy was to shame the Japanese people’s native appearance and claim that eating McDonald’s burgers would make them taller, whiter, and blonder.

“The reason Japanese people are so short and have yellow skin, is because we have eaten fish and rice for two thousand years,” he said in 1971. The successful marketing strategy for the first Asian McDonald’s outlet capitalised on Japan’s “cultural cringe”. Their marketing strategies for Sri Lanka and the Indian subcontinent at large also pivot on this aspirational value.

The concept of cultural cringe is an internalised inferiority complex that causes people in a country to dismiss their own culture as inferior to the culture of others. This complex is prevalent in Sri Lanka, and is exploited by many industries, such as the beauty industry for instance. Although this desire to adopt Western standards exists in all aspects of Sri Lankan society, those with money are able to buy into it more, whether it is by spending on a private or overseas education, using imported hygiene products — or indeed, by buying a Chicken McSpicy at Mcdonald’s.

“When McDonald’s first came to Sri Lanka, I remember watching movies and shows where people eat there, and so naturally, I was really excited to be able to eat there myself.” said *Sampath De-Silva, who frequents McDonald’s multiple times a month. “I felt like I was in some other country, not Sri Lanka.”

Despite the obvious concerns about diet, the aspirational value that Sri Lankans place on fast food could potentially have some benefits. In America, the fact that fast food restaurants are easily accessible is what contributes in large part to the widespread health and nutrition issues the country is facing. However, due to the way fast food chains operate in our context, it seems unlikely that Sri Lanka will succumb to those same issues — or at least with the same seriousness. Most Sri Lankans dine at fast food restaurants on occasion, and more frequent patrons still do not depend on it as their primary diet staple. In the long run, this could potentially deter—or delay—us from experiencing the same consequences at the hands of these conglomerates.

.jpg?w=600)