.jpg?w=1200)

Internationally, Sri Lanka is often commended for its policies concerning maternal health, especially when pitted against neighbouring countries like India. Since the 1950s, there has been a steady decline in maternal mortality: a feat that is often credited to universal health care services and a well-developed health infrastructure. Despite this heavily eulogised commitment to maternal health, Sri Lanka has extremely strict abortions laws, which contribute significantly to the country’s maternal mortality rate.

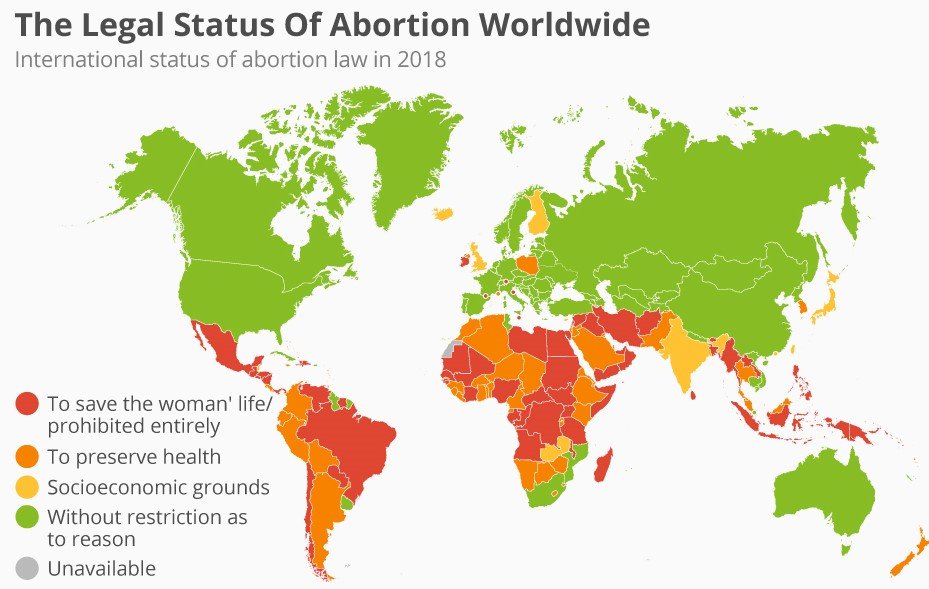

According to the Penal Code of 1883, the only case in which an abortion is permitted in Sri Lanka is if the mother’s life is at risk. This law was made by the British, during their colonial rule of Ceylon, and has not been amended since. Ironically, in the UK, abortions were legalised in 1967.

Sri Lanka’s austere abortion laws, however, have not deterred women from seeking them out illegally.

“There are over 600 women having abortions daily in this country,” said Paba Deshapriya, human rights activist and co-founder of the Grassrooted Trust. “These abortions are almost always done in backdoor operations, or in many cases by the individuals themselves. They can be extremely dangerous, and patients who undergo them run the risk of contracting severe infections in the aftermath of the procedures.”

These realities are difficult to ignore. For this reason, Sri Lankan law states that in the event that complications from an abortion do occur, patients can seek post-abortion care. In 2015, the Ministry of Health added a guideline to the law, which states that doctors are not legally required to report such incidents.

Avoidable Circumstances

The word abortion, as it is commonly used, refers to the deliberate termination of a pregnancy. The method that an individual may use to procure an abortion, lies on a spectrum that is quantified by legality.

In countries where abortions are legal, such as Switzerland, Cuba and Germany, the spectrum is narrow. One may choose to get the procedure done either surgically, or by using pills. Both these methods are low risk, and the care that one would customarily receive in the aftermath is minimal. Many of these countries also offer pre-abortion care, where patients can consult with doctors before having the procedure done, and talk about ways to prevent a future unwanted pregnancy.

In countries like Sri Lanka, where abortions are illegal, the spectrum is much wider. To get procedural abortions done illegally can be very expensive, which is why many people turn to non-medical, DIY methods of inducing an abortion. Therefore, when a person does seek out post-abortion care, the complications are often extreme.

Professor Wilfred Perera, a gynecologist who has worked in the field for over 50 years, has witnessed many of these extreme cases.

“Earlier in my career, I would have to treat many cases where knitting needles were used to induce an abortion,” he said.“Patients would come to me in excruciating pain, from having stuck the needles in too far. I have had to operate on patients to pull out needles from inside the abdomen.”

Deshapriya also recounted a similarly alarming incident that occured in Anuradhapura, where a woman came into hospital with an acute stomach pain. After being administered painkillers, the woman returned weeks later with an infected uterus. She was taken into the operating room, where the doctors discovered that her infection had become so putrid that small, ring-like worms had formed inside her womb.

The woman had administered an abortion using an enderu natti, which is the branch of a recinus plant. There is a type of chemical known as recin that is found inside this plant, which can induce an abortion.

By using this method without any guidance or sanitation, the woman had contracted an infection so severe that it almost killed her. She had not known that post-abortion care was available, and had therefore let the infection get to an extremely dangerous point before seeking help.

“In this case, it was extremely unfortunate as this infection could have been prevented much earlier in its development,” said Deshapriya.

Even when abortions are practiced ‘medically’ in underground operations, there is no regulated way to determine whether these practices are safe or not.

*Thiruni (name changed), was able to get her abortion done medically through a doctor who was seeing patients in secret. It’s difficult to determine how safe this procedure was, given its clandestine nature. After the procedure, Thiruni experienced many side effects, including irregular menstrual cycles and immense abdominal pain.

“Had I known that I could seek out care after having the procedure, I most definitely would have,” she said. “The experience was quite a bad and painful one, and in that state I would’ve sought out help, even it appeared on my medical records.”

The Ministry of Health’s guidelines for post-abortion care are aimed at reducing the casualties which occur from unsafe abortion practices. However, there is very little awareness about the availability of such services, making it difficult for women to access them.

A Cultural Taboo

In South Asia, cultural norms can often hold more social power than laws themselves. In India, for example, despite abortions being legal under many provisions, the cultural stigma is so strong that people aren’t aware that such laws even exist. As a result, many women who could terminate a pregnancy legally still solicit illegal abortion methods. The fear of being shunned by their communities prevents people from seeking out legal services available to them.

In Sri Lanka, this same stigma can impede women from seeking out post-abortion care.

Kumari* was 20 years old when she found out that she was pregnant. As she recalls this, a palpable fear spreads across her face, as if she is re-living the moment in real time.

“I was in a terrible relationship. I led this double life where I pretended like everything was fine, but I was getting beaten up on a daily basis, and spent most of my money on makeup to cover up the scars. If I brought a child into this, I would have been forced into a marriage that might have killed me,” she said.

This fear drove her to seek out an abortion through an ayurvedic doctor. She wanted to get the procedure done medically, but couldn’t afford the 60,000 rupee charge. It has been years since then, but she still faces heavy cramping and stomach pains as a result. The recovery process took a severe emotional and physical toll on her, but never once did she think of visiting a hospital to seek out help.

“I didn’t even know that was something I was able to do, but even if I did, I don’t think I would have,” she said. “ I had not told anybody about what I had done, not even my mother. If I went to a hospital for help, it would’ve felt like I was outing myself in some way”.

The social stigma surrounding abortions also has an effect on how patients are treated when they seek out post-abortion care.

“If a doctor treats you after an abortion, they cannot officially write that in your medical records, so they will write that you have miscarried. This becomes a permanent part of your medical history,” Deshapriya said. “If in the future the same woman decides to have a baby, doctors would have to address her past ‘miscarriage’ and she will run the risk of being outed to her family. She will also be put through unnecessary monitoring during her current pregnancy.”

Women with a history of miscarriages often have to be monitored more closely during a pregnancy, as their chances of miscarrying again are high. If the woman actually had an abortion, there would be a seperate set of precautions she would need to take during her pregnancy, depending on how she had the procedure done.

The mislabelling of abortions as miscarriages results in an inaccurate portrayal of a the patient’s medical history.

Post-abortion care in Sri Lanka is a vital service, especially considering the spate of illegal abortions that occur in the country. However, having this service doesn’t necessarily address the root cause of the problem.

“It’s difficult to talk about post-abortion care in this country, because abortion is not legal,” said Perera.

Deshapriya also echoes these sentiments. According to her, without destigmatising abortions, while also cultivating a culture that is open to talking about sex, sexual health and contraception, women are going to continue to put themselves through unnecessary harm to have these procedures done.

“Post abortion care is a first step, but then at some point the discussion needs to be moved beyond that,” she said. “This service wouldn’t be so necessary if abortions were practised safely.”

.jpg?w=600)