Sarath Lal Kumara was about 27, and newly married, when the Sri Lankan government began hunting down socialists in the country. This was during 1987 – 1989 — a period later described as “the years of terror” — when the Marxist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), today a political party, then an armed rebel group, launched its second insurgency against the government.

At the time, Kumara, then still in university, and living in Moratuwa, was pressured by his wife and mother to get rid of a large collection of leftist writing and books on Soviet Russia, to avoid persecution.

“People, especially the youth from the south, were suspected of being rebels and were questioned and persecuted by the authorities,” Kumara told Roar Media.

“My mother used to call me, crying, and ask me to get rid of the books. When that failed, she would call my wife. The authorities used to come in the night and check people’s libraries. They would act on tip-offs. If you were a teenager or a university student’s age, and if you were from Matara, Tangalle or Galle [in the South] you would become an immediate target. So one day, I buried them in the foundation of the house that I was building,” Kumara recalled.

During those three years of the second JVP insurrection, Kumara said, many readers who had collected thousands of works of Russian literature were forced to get rid of their collections in order to avoid persecution.

“They couldn’t keep them at home, so they were thrown away, or burned. This was the mindset of the time; books disappeared, just like people did,” he said.

Kumara’s collection of over 400 Soviet books and magazines remained buried until 1989, when government forces overwhelmed the youth rebellion. “After the death of Rohana Wijeweera [the leader of the JVP that led the rebellion] things started to calm down,” Kumara recalled. “That’s when I remembered the books. I retrieved them, and they were in good condition. That collection, since, has grown larger.”

Sri Lanka’s Other Literary Identity

Kumara believes the ’80s rebellion was the only blemish in the long history of fascinated readers of Russian and Soviet literature in Sri Lanka.

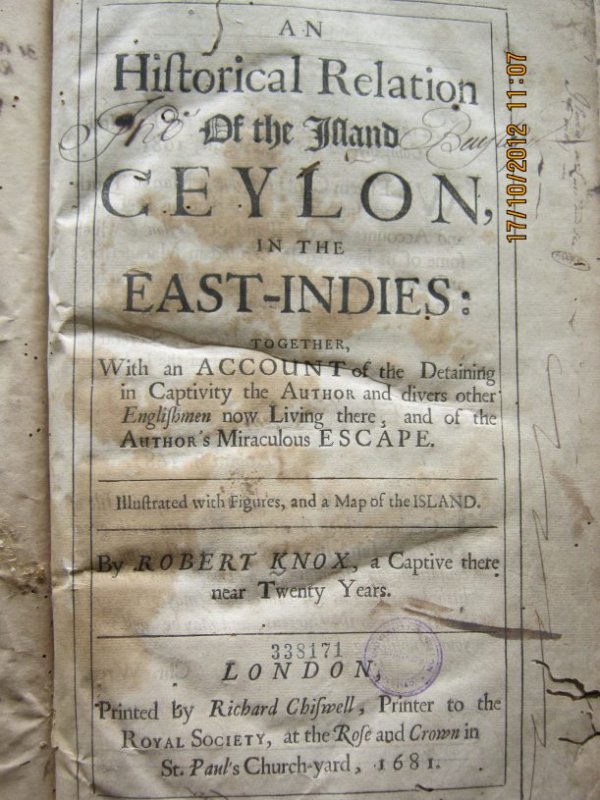

After Sri Lanka began diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union in the late 1950s — under then-prime minister S W R D Bandaranaike’s administration — the country received an influx of Soviet literature. Later Sri Lankan students also received scholarships to study in Russia. This produced the likes of Dedigama V Rodrigo, Rohana Wijeweera the leader of the JVP and Oruwala Bandu.

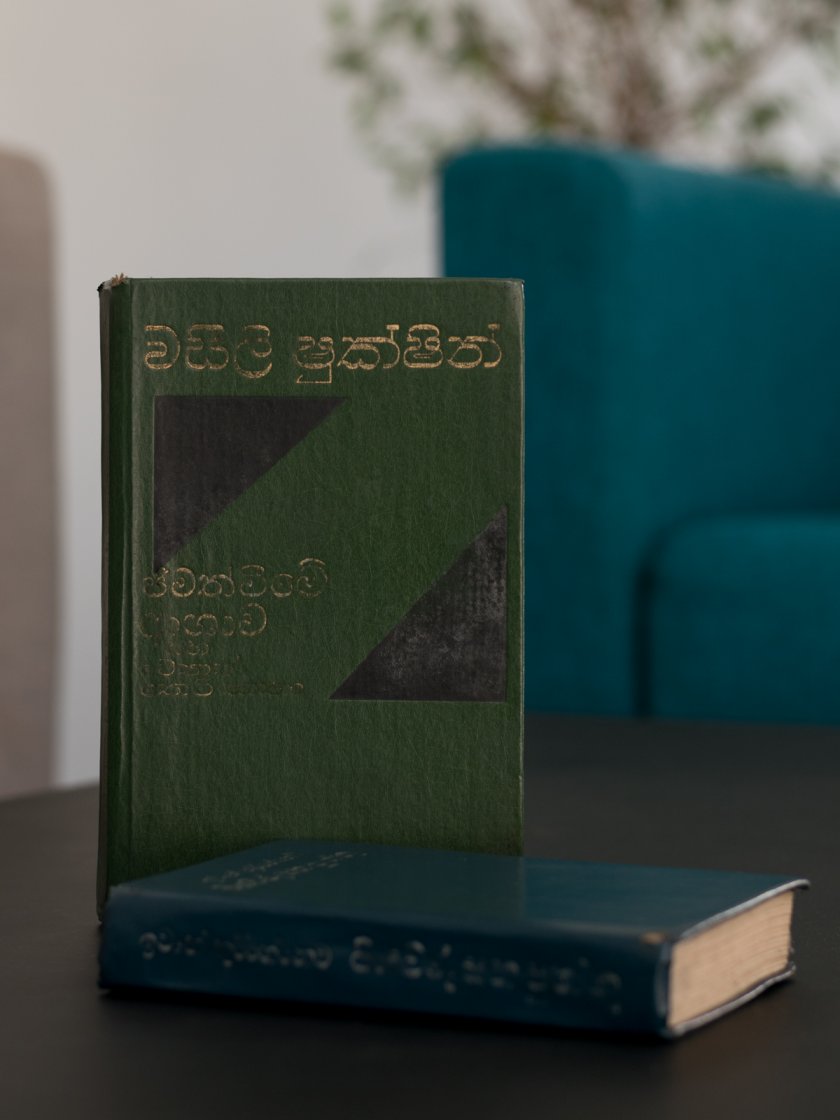

Of these, it is Rodrigo’s works that have made the largest contribution to Sri Lanka’s literary circles, Kumara feels, for if not for his 1,000 odd Sinhala-Russian translations that survived the ’80s rebellion, he believes the country’s love for Russian literature would have diminished.

While it was political literature that most fascinated readers at the time, it was not always the communist or leftist thinking that attracted the average reader. Translated books and novels were cheap and widely available in bulk, although one author described it as “one way literature”, with Russian literature available aplenty locally, but Sinhala literature never taken to Russia.

“Other than our very own ‘Sri Lankan literature’ that is unique to the country, we also have our own unique Soviet literature,” Kumara explained.

“We were colonised thrice but we never adopted their [the colonisers’] literary identity. English literature is massive but we never properly adopted it. Either it was intentional or as a nation we resisted it, as a subconscious move against colonial rulers. But here we are embracing the literature of an eastern European nation that has had no historical connection to Sri Lanka. It has had such a massive influence on the country’s culture, reading habits, as well as literature.”

Kumara, now 59, has come a long way since he saved his first collection of books from being burned. He is now the owner of ‘Rusiyawa Publishers’ — one of three publishers in the country that translates Russian books to Sinhala. He also operates ‘Dyuyshen’s Bookshop’, located in Nugegoda, that specialises in Sinhala-Russian literature.

“In 2005, I was asked to take part in the publication of a magazine called Rusiyawa (Russia), with the help of the Russian Cultural Centre. I’ve been the editor of the publication since then. The magazine was to replace another called the Lankan-Soviet Magazine, a Sinhala publication that published cultural pieces about the Soviet Union. After the collapse of the Union it, that publication stopped printing as well,” he said.

Subsequently, Kumara volunteered to help other publishing houses and bookshops that sold Russian translations at the annual Colombo International Book Fair. This was when he first had the idea to start his own bookshop. “I published a magazine and I sold books. People started asking me why I still don’t have a bookshop,” he said.

So in 2013, he found a small space at the co-op building in Nugegoda, where he set up a store. “I spent many nights thinking about what I should call it. Then one night, I recalled the story of Chingiz Aitmatov’s The First Teacher [translated to Sinhala as Guru Geethaya]. Duishen is the protagonist teacher in the story. I wrote it down immediately, groggy from having woken up from deep sleep, in case I forgot in the morning.”

Kumara operated that bookshop there for six years until he relocated in 2019 to a different building, also in Nugegoda, where he is currently at.

End Of The Golden Age

“One of my customers told me his personal experience,” Kumara narrated to Roar. “During the terrors [of ‘87-’89], he had burned all of his books. But he could not bear to burn them outside in his garden. So he had piled his entire collection on his bed, poured gasoline, and set it alight. But he told me that memory still haunts him. So much so that even to this day, he cannot sleep on a bed, and sleeps on the floor as a punishment.”

The same people who were forced to get rid of their books, who burned piles of carefully collected literature out of fear of being persecuted, are the ones who have today, have returned as avid collectors to Kumara’s shop and are some of his most popular customers. These people, some of whom are parents now, have also passed down their love for Russian writing to their children, creating a fourth generation of Sri Lankan readers.

But despite his loyal client base, Kumara feels the golden age of Sinhala-Russian literature ended in the ’80s. “People still come to my bookstore and people still seek out these books, but whether that will continue into the future, I cannot say,” he said.

Kumara and other publishers of this genre depended heavily on Colombo’s annual International Book Fair, both as a form of income and as a way to attract newer readers — but the book fair did not take place this year, due to the travel restrictions imposed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Last year also, the International Book Fair took place with only a minimal crowd, due to COVID-19, and we could not get the same business as we did in the years before. This year, the fair didn’t happen at all, unfortunately, since the country was going through yet another COVID-19 wave,” he said.

Despite these fears, Kumara is determined to move forward. He has dedicated his life to these books and will continue to do so until the end, he said.