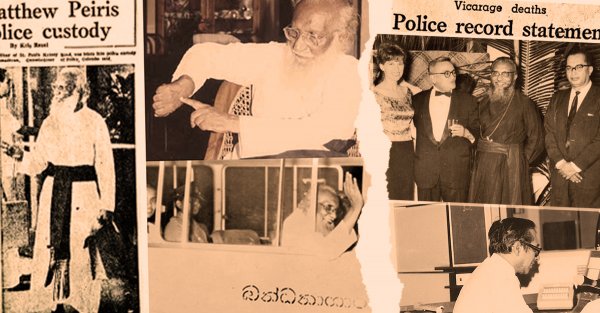

Given the stigma surrounding mental illness, you would think mental healthcare in Sri Lanka is still at early stages; but it was in 1839 that British Governor James Alexander Stewart-Mackenzie first introduced an ordinance to establish mental asylums in Sri Lanka.

Hendala Lepers Asylum

The piece of legislation called the ‘Lunacy Ordinance’ was enacted for the better care of mental health patients, who had until then languished in jails. But rather than house them in separate facilities, the mentally ill were first removed to a wing of the ‘Lepers Asylum’, then in Hendela.

Borella Mental Asylum

It was in 1847, thanks to the efforts of Dr. Christopher Elliott, the Principal Medical Officer in Ceylon, and Governor Stewart-Mackenzie, that a hospital for the mentally ill was built close to Campbell Park in Borella, Founder, Director and Consultant Psychiatrist at the National Institute of Mental Health, Dr. Jayan Mendis told Roar Media..

The Borella facility was used for confinement, said Dr. Mendis, who explained that there was no ‘treatment’ for the mentally ill at the time. “They were simply housed there, and given meals.”

With time, however, conditions at the Borella mental hospital deteriorated due to overcrowding, leading to the death of many of the inmates. A decision was then made by Dr. W. R. Kynsey, Principal Civil Medical Officer at the time, and Governor Sir William Gregory to build a new asylum for the mentally.

Female patients at the Angoda mental hospital converse with nurses outside their ward. Image credit: Minaali Haputantri/Roar Media

There were, however, many delays before the new facility was complete; it took seven years of discussions between the relevant parties for the project to take off the ground, and construction took a further fifteen years, according to Emeritus Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Colombo, Nalaka Mendis.

Jawatte Mental Asylum

The new asylum was finally built in 1889 on a 14-acre site in an area known as ‘Kumbikele’, near the Cinnamon Gardens in Jawatte—the location known today as the ‘Independence Arcade’. The Jawatte Lunatic Asylum was built to house two-hundred and fifty inmates and contained private rooms, dormitories and seclusion rooms for the very disturbed patients, Dr. Jayan Mendis said.

Medical research had not yet made a breakthrough in the treatment of mental patients, and patients were still mostly confined and given meals. With time, and a lack of understanding about mental illnesses, the numbers of those afflicted steadily increased. Predictably, conditions at Jawatte Asylum too deteriorated, leading to an outcry by families of patients to British authorities, saying there were no facilities for the sick.

Angoda Mental Hospital, Or The National Institute Of Mental Health

This forced the closure of the Jawatte Mental Asylum, after which the construction of a new mental hospital on a 125-acre piece of land in Angoda began in 1917. “This is a huge hospital complex, with a large administrative block and six three- storey buildings—each able to contain about hundred patients,” Dr. Mendis said.

A patient mends a cane chair at the Angoda mental hospital, as part of his occupational therapy. Image credit: Minaali Haputantri/ Roar Media

“Together, the complex is able to house about one thousand five hundred patients, in addition to quarters for those who work, quarters for doctors, a paddy field, garden facilities, etc.,” Dr. Mendis said.

Dr. Mendis explained that to be mentally ill was to be “emotionally or behaviourally disturbed” —and have no knowledge of the emotional or behavioral disturbance or deviance. He explained that not all mentally ill persons were dangerous—“In fact, only about 1% can become dangerous, and it’s up to psychiatrists to determine which ones are dangerous and treat them accordingly.”

Things have changed greatly since 1950s, when the drug ‘chlorpromazine’ was synthesized in France, Dr. Mendis told Roar Media. The drug was found able to reverse the symptoms of mental illnesses and patients who exhibited positive results were reintegrated into society. Today, more than fifty drugs with which mental patients can be treated exist.

All patients at the Angoda mental asylum, officially known as the National Institute of Mental Health, are being treated, Dr. Jayan Mendis said. Conditions are also much better, with inmates offered recreational activities and a glimpse into the outside world.

Stigma

Things can get better though, Dr. Mendis add. The stigma surrounding the mentally ill is still very strong, with the perception that patients are unpredictable and could be dangerous. To the contrary, Dr. Mendis explain, the mentally ill are silent suffers and need all the help and support they can get.

“It’s important to detect early, treat early, treat adequately, treat quickly, continue treatment and follow up treatment,” the doctor said. “Treat them like equals. Try and engage them in work,” he further encouraged.

The Angoda mental hospital has undergone further changes in recent years. Since 2008, it has moved from centralized to community-based treatment so that patients can receive treatment at base hospitals and clinics, and can continue to live within their communities.

Renovations were made to give the wards a facelift. Image credit: Minaali Haputantri/ Roar

According to reports, this practice has been especially implemented with great success in the post-war North and East, where progressive treatment models ahead of Colombo have been embraced.

From being confined among ‘untouchables’ in the Leper’s Asylum at Hendala, to receiving state-sponsored care and treatment at Angoda, the welfare of those mentally ill has progressed over the years, but Dr. Mendis believes more must be done to remove stigma. “Even the media continues to portray the mentally ill through ‘dark’ images,” he said. “This perpetuates the stigma surrounding mental illnesses. We must all play our part to removing the stigma surrounding these people.”

Cover: The current ‘Independence Arcade’ was once the Jawatte Mental Asylum. Image credit: Minaali Haputantri/ Roar Media