Male-dominated Sri Lankan colonial society looked upon European women as, essentially, adjuncts to the White male administrators, planters and soldiers who ran the show. However, a rare cookery book, available in the Colombo Museum Library, gives us an insight into their lives.

The year 1917 was not a good one for the British Empire. The First World War had dragged on for three years, a purgatory of mutual slaughter, in which thousands died for a few kilometres of land. In Spring that year, the French Army mutinied. In an effort to give the French soldiers a rest, the British Army launched a series of futile offensives which ended in the usual massacres.

By then, hundreds of thousands of British Empire troops had been wounded or captured. Combined with St John’s Ambulance Brigade, the British Red Cross Society helped the military and naval medical services to treat the sick and wounded. They also provided relief for British prisoners of war, mainly through the delivery fortnightly of 5kg food parcels, each containing enough beef, cocoa, biscuits, milk, fat and cigarettes to keep two men going for a week. They managed to deliver over 2.5 million parcels during the course of the war.

This all required funding, and the British Red Cross managed to raise nearly £22 million through an assortment of funds, collections and donations. One such effort gave birth to an extraordinary publication, the Allied Forces Cookery Book, one of the first modern cookery books in Sri Lanka (then a British colony). Published by H.W. Cave, Colombo, in November 1917, it contained over 650 recipes, sent in by well-wishers from all over the island.

Australian troops sightseeing in Sri Lanka during the First World War, image courtesy State Library of South Australia

Caviare on Toast

The famous British home economist and celebrity chef Marguerite Patten included in her 1999 book Century of British Cooking two of the recipes from the Allied Forces Cookery Book: “Bread Soup” and “Trout Cream”. In the introduction to the latter recipe, she noted that:

“… there was great unrest until official rationing came into force in 1918. It was felt that, while poorer people suffered greatly from lack of food, the rich people were able to buy more food and hoard it too. I think that this recipe rather illustrates that point. It obviously came from someone who had access to plenty of eggs, milk and cream as well as freshly caught fish.”

Patten had worked during the Second World War as a senior Food Adviser at the Ministry of Food, educating people on keeping healthy with their available food rations, so she knew what she was talking about.

Marguerite Patten (left) presenting her TV cookery show in 1950, image courtesy BBC

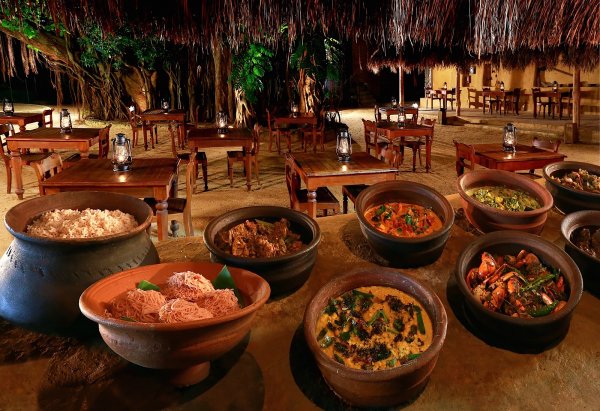

The recipes in the Allied Forces Cookery Book came from European women resident in Sri Lanka who, as a class, had a far better standard of living than the indigenous inhabitants. These contributions reflected their position in society. “Caviare on Toast”, submitted by Miss Olney of Watawala, stood out. Even then, caviar cost far more than other types of food, and lay out of the reach of most people in Britain, let alone Sri Lanka.

Kitchen Regions

In colonial Sri Lanka, the class distinctions then extant in Britain repeated themselves, magnified considerably, with the colour bar heaped atop the divide between the white Dorai and the black “coolies”. The green baize door, dividing the upper-class upstairs of the English country mansion from its servant-occupied downstairs, found itself replicated in the Sri Lankan bungalow in which the front portion of the house remained distinct from the kitchen and the servant quarters at the back.

According to Ethel M Cooper, an Australian, writing in 1910:

“It is sometimes said that for an English lady it is very infra dig to enter her own kitchen. It is the duty of the appu (butler) to superintend the whole bungalow, and that is considered by many to be sufficient.”

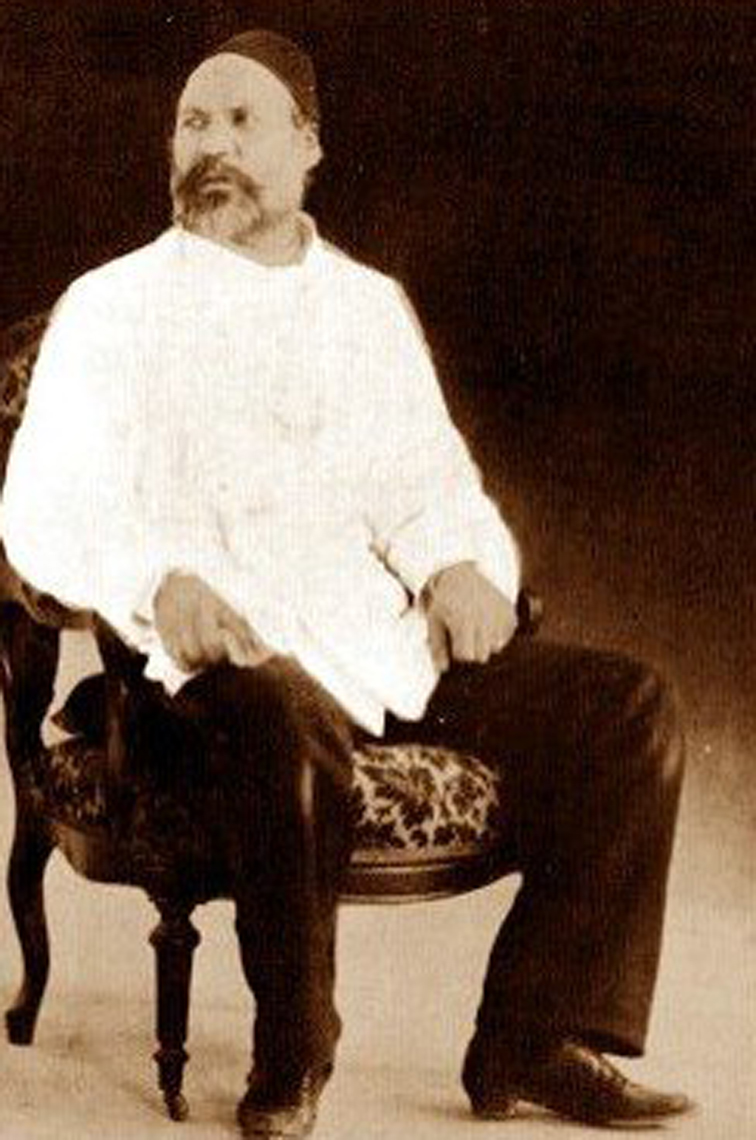

Abraham Sofaer as “Appuhamy” in Elephant Walk, courtesy Vernon Corea website

The rarity of visits by her ladyship to the kitchen gave the appu essentially a free hand. Not every appu was as imposing as Appuhamy in the 1954 Paramount film Elephant Walk—nor was every estate bungalow as impressive as the mansion depicted in it —but the spirit remained the same. Another Australian lady, thoroughly disillusioned with the reality of plantation life, related:

“… the story of the over-confident woman who bet that she could go into her kitchen at any hour of the day and find everything running smoothly and cleanly. She was ‘taken up’ by the house party who went in full force to the kitchen regions, and found the cook washing his feet in the soup tureen!

Wartime shortages

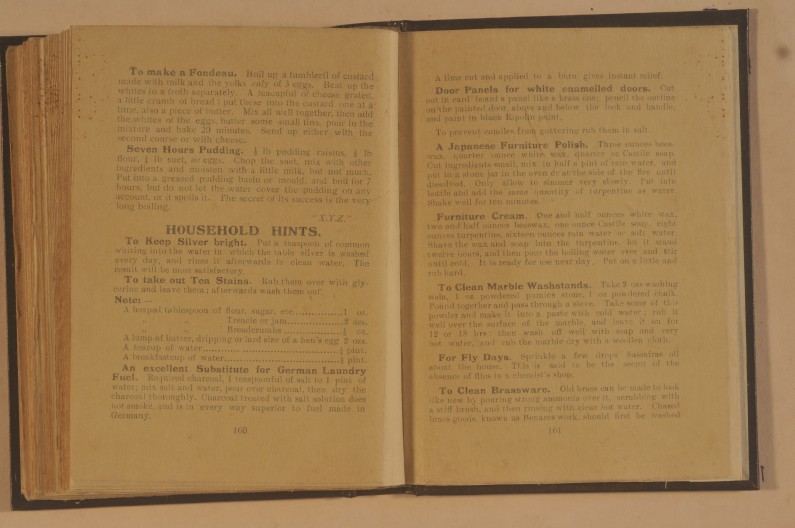

Nevertheless, the Allied Forces Cookery Book showed that quite a few White ladies did venture into their “kitchen regions”, at least to supervise the manufacture of some item of haute cuisine. Several visited the kussiya regularly, as evidenced by “Household hints” at the end of the book. One hint has direct relevance to cuisine: “Dry ginger may be obtained in any bazaar, grind it and bottle it, when it is always ready for use.”

Most of these hints relate to cleaning silver, brass, furniture, and so on, displaying a very European predilection for keeping things polished and squeaky clean. “An excellent Substitute for German Laundry Fuel” (charcoal treated with salt solution) provides an outstanding example, showing of how to deal with wartime shortages.

A page from the Allied Forces Cookery Book, image courtesy Colombo National Museum

Other recipes also reflected the effects of scarcities caused by the ongoing struggle. For instance, Mrs. W.A. Chamberlain of Hauteville, Agra Patanas, shared her technique for making “Maraschino Gin”. Most authorities on mixing cocktails specify that for making Maraschino Gin you need Maraschino liqueur. However, this liqueur, distilled from Marasca cherries, came from the Dalmatian coast, a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, with which Britain was at war. So Mrs. Chamberlain’s recipe substituted lemons and Seville oranges for Marasca cherries, and recommended daily shaking of the mix for a fortnight.

Miss Olney’s “Salad Dressing (Lord Kitchener’s Recipe)” provided another example of the effects of war. Horatio Herbert Lord Kitchener of Khartoum, the War Secretary, lost his life when his ship hit a mine in 1916. A veteran soldier, one wonders whether he had the time to develop such an exotic condiment!

We can only guess whether Mrs. Mary F. Coombe of Bathford, Dickoya, suggested “Pigeons a la Ste Menehould” because of wartime poultry shortages, or because the overpopulation of her rafters by the noisy and irksome birds caused her to seek revenge on the species. The former seems a possibility, given the small number of chicken-based dishes. On the other hand, eggs certainly did not appear to be in short supply from the multiplicity of recipes requiring them; particularly for cakes and desserts.

Europeans living in the tropics had a propensity for getting sick, so the book contained a good number of recipes for invalids. Mrs. G.C. Bliss of Glenlyon, Agrapatana, contributed “White Wine Whey”, “Egg Nog” and “Egg Nog, Hot”, as well as the perennial “Beef Tea, Raw”; while Mrs Hunter Blair of Hoolankande, Madulkelle, provided “Chicken Custard for an Invalid” and Miss Cotton advised on how “To cook an Egg for an Invalid”.

Yorkshire Pudding and Arabi Pasha

The lack of domestic dishes in this tome, which featured “Yorkshire Pudding” (from Mrs. E.E. Ellis Labugama Estate, Waga), epitomised the gulf between the European colonisers and the colonised indigenous population; although many used local ingredients, such as “Gateau of Fish and Rice” from Mrs. Ralph Bennet of Lonach, Watawala; or “Coconut Cakes” from Mrs. Blackmore of Carolina, Watawala.

Against this background, two dishes stand out. Mrs. Egan of Fernlands, Pundaluoya, contributed “Arabi Pasha”, an Arabic saffron rice dish based on fried tomatoes named after the Egyptian patriot exiled to this island. Miss Ethel Northway of Elston, Puwakpitiya, provided a recipe for “Lime Pickle”, indistinguishable from lunu dehi. The Northways came to Sri Lanka in the 1840s and remained until the 1970s, most of that time based at Devitura, near Elpitiya.

Arabi Pasha, image courtesy Wikimedia

These dishes provide a bridge between the European cuisine of the British colonial population and that favourite among Sri Lankan cookery books, the Daily News Cookery Book. Brought out by Mrs. Hilda Deutram in 1927, this kitchen manual proved the ultimate in Sri Lankan fusion, bringing together the diverse dishes of the island’s many communities, and went on to four editions. The latest edition still features “Beef Tea”, similar to Mrs. Bliss’ recipe.

An earlier edition stated that “A country’s culinary prowess is often an index of its domestic well-being.” By that measure, the Allied Forces Cookery Book indicates that, whatever the prosperity of the general population, notwithstanding the adversities of the First World War, the European elite did just fine.

Note: Unfortunately, this intriguing book is not accessible to readers, except to visitors to the National Museum Library, Colombo; or to the Imperial War Museum in London.

Cover image: http://cookiejardc.com