Many Sri Lankan Tamils have English or otherwise European names, and are often confused with Burghers or Eurasians. How this came to be constitutes a vital part of the evolution of modern Sri Lanka.

The story begins with the British invasion of the island in the late 18th century and conquest of the lowlands, hitherto occupied by the Dutch. Unlike previous European invaders, the British were more concerned with Ceylon’s strategic position in relation to India, and so expedience and budgetary constraints played a major part in their decision-making on the island.

After the British occupied the country 1796, they appointed Dutch Burghers, descendants of the Europeans employed by the former colonial power, to positions in the administration, to mediate between them and the native population. The historian, lawyer and politician Colvin R de Silva noted, in his monumental study of the early period of British rule Ceylon Under the British Occupation (pp205-208), that the British brought in East India Company apparatchiks, mostly South Indian natives, to replace native “headmen”of the Mudliyar and Arachchi classes.

This led, de Silva noted, to a revolt in 1797, following which the British built up a privileged minority of “natives” to supplement the Burghers in the higher altitudes of society. This privileged elite came from the most educated members of society, a disproportionate number of whom were Tamil, due to a peculiar circumstance of history.

American Missionaries

According to de Silva’s Ceylon Under the British Occupation, when the British government slashed expenditure on education on the island due to budgetary constraints, it relied heavily on Christian missionaries to carry out educational activities. A significant portion of this effort was made by the American Ceylon Mission (ACM), established by Rev. Samuel Newell in 1813, in Jaffna, in the Tamil-dominated north of Ceylon, as part of the evangelising effort of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Although Americans had been visiting the island since 1788, as spice traders and whalers, the British, citing the ongoing war with France, refused to allow the Americans to proselytise elsewhere — a ban which lasted far longer than the war of 1809-1814, the penultimate in a series of Napoleonic Wars waged all over the world.

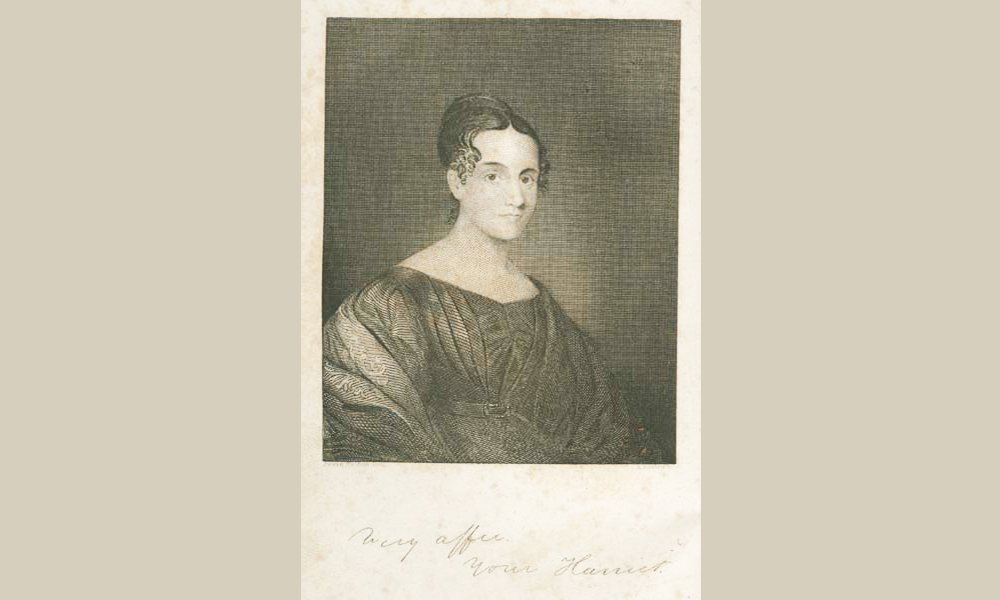

In 1816, the ACM established a school at ‘Tillipally’ (as they called the town of Tellippallai), today’s Union College, also in Jaffna, in the Tamil-dominated north. In 1823, they inaugurated the Batticotta Seminary (which evolved into Jaffna College), Ceylon’s first modern university-level institution at Vaddukoddai, also in the north. The next year, prominent ACM missionary Harriet Winslow (ancestress of later Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles and CIA head Allen Welsh Dulles) founded Uduvil Girls’ College, Asia’s first girls’ boarding school, in the Tamil-dominated north.

In 1848, American doctor and missionary Dr Samuel Fiske Green opened the first modern medical school and teaching hospital (South Asia’s second modern teaching hospital, which later came to be known as the Green Memorial Hospital) in Ceylon, at Manipay — again, in the northern part of the island. The ACM also set up the first printing press in the north in 1820 and in 1841 began the island’s second oldest newspaper, the Morning Star, there too.

The ACM weren’t the only missionaries making inroads in the country; the Wesleyan Methodist Mission (a British Methodist missionary society) already had bridgeheads in the Eastern Province, and followed on the heels of the ACM, founding Jaffna Central College, in the north, in 1817. The Anglicans (from the Church of England) also established St John’s College, in Jaffna in 1823, and it was the Roman Catholic Church that attended to the educational needs of its flock in Jaffna long after the ACM.

English Handles

These activities resulted in profound changes in the traditional, caste-based Hindu structure of society. An English-speaking, mainly Christian elite emerged in the northern peninsula. The missionaries, when baptising converts, would give them Christian names and surnames, often those of sponsors of the mission.

These names could be Biblical — such as James, Paul, Simon, and Solomon. Anglicans and Methodists often received English surnames, such as Crossette, Crowther, Handy, Spencer, Williams and Watson. Those baptised by the ACM, however, invariably received the English monikers of eminent American Protestant families, mostly originating from New England. These included Armstrong, Arnold, Barr, Buell, Chapman, Cooke, Cotton, Curtis, Dwight, Hensman, Hoole, Hopkins, Lawton, Lodge, Macintyre, Martyn, Mather, Mills, Nevins, Niles, Phillips, Riggs, Sanders, Stone, Strong, Taylor, Wadsworth and Wilson.

Catholics were generally named after Christian saints, notably Anthony, Bastian, David, Diego, Emilianus, George, John and Joseph, often tagging “pillai” (child) at the end; or Biblical entities, such as Cherubim.

Names Of Note

Generations later, many people reverted to their Tamil names, either out of patriotism, or for expediency. For instance, E.M.V. Naganathan, the eminent politician, was originally Hensman. Several others decided to adopt double-barrelled surnames, with their baptismal monikers connected to their ancestral Hindu handles by hyphens, for example Crossette-Thambiah, Nevins-Selvadurai and Philips-Arasakumar.

“[In fact] all the Protestant Christian Tamils are related or connected,” Sereno Barr-Kumarakulasinghe, a eco-tourism entrepreneur with such a double-barrelled name, told Roar Media. For example, he said, his own family has connections with the Mather, Page, and Phillips families, as well as with Federal Party founder S.J.V. Chelvanayakam, who in turn had Wilson connections.

Exemplifying these relationships, the Paul family of doctors, originating in Manipay (patriarch, William Paul being one of Green’s first medical graduates), who occupied several residences in Ward Place, has links with the Cooke, Crosette-Thambiah, Edwards, Phillips, Snell and McGowan-Tampoe families. The Cooke family married into the Abraham, Arnold, Black, Francis, Lawrence, Mather, Strong and Wilson families, while the Page family has ties to the Dwight, Gardiner, Mather, and Strong families.

Among this disparate community of English-named Tamils, several stand out in history — from Jaffna College co-founder James Prince Cooke, pioneer photographer S. K. Lawton, pioneer surgeon S.C. Paul and Senator Chittamapalam Gardiner to mathematician and physicist Christie Jayaratnam Eliezer, author of the 1978 Constitution Alfred Jeyaratnam Wilson and current cricket commentator Russel Arnold. This small, but homogenous and refined social stratum has had an impact far beyond its meagre numbers, and can be found today in positions of influence on every continent, some of them even in New England, from where their names once came.