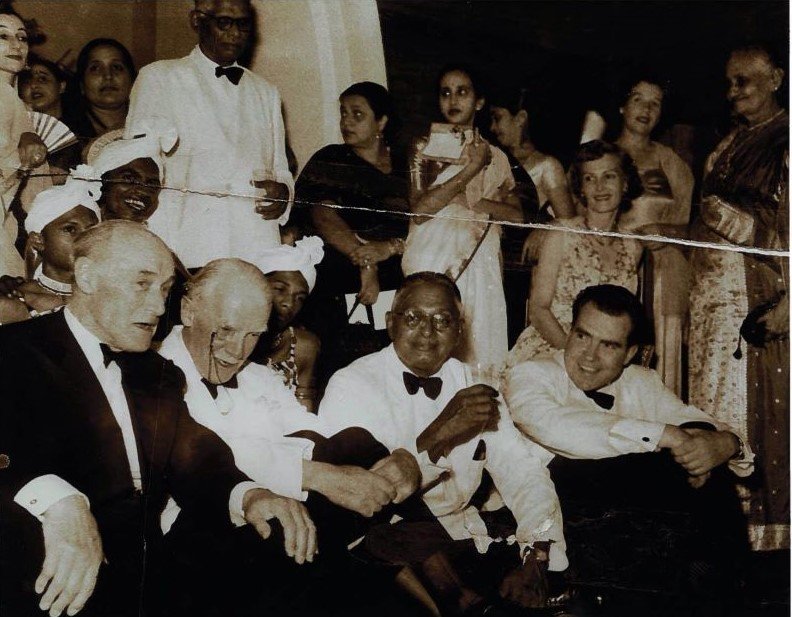

On 27 November 1953, after a month touring 15 Asian countries, US Vice President Richard M Nixon, accompanied by his wife Pat, arrived at Ratmalana Airport on a three-day visit to Sri Lanka, then known officially as “Ceylon”. It was the first visit by a US holder of that office. He immediately broke protocol by exchanging greetings with the crowd of onlookers and fielding questions at an impromptu press conference, before being whisked off to Temple Trees, Prime Minister John Kotelawela’s official residence.

Nixon behaved characteristically. Remembered today because of the Watergate scandal which led to his resignation, for slandering his opponent Helen Gahagan Douglas by calling her the ‘pink lady’ (earning him the sobriquet ‘Tricky Dick’), and supporting McCarthyism, he could also be a pragmatist: most significantly, he ended the Vietnam War, and visited China, normalising relations with that country.

Born to a poor family in rural California, Nixon had to fight his way to the top to become an expert politician. Missing a chance to go to Harvard, he instead went on to pursue a successful legal career, including a stint with the US Navy, and just six years after election to the US Congress, became Vice President. President Dwight D Eisenhower gave Nixon serious responsibilities, the collaboration between the two making him the “first modern vice-president”. The US foreign policy establishment, preoccupied with Europe, had little familiarity with Asia, and Eisenhower also assigned this area to his VP.

Rubber For Rice

US missionaries played a vital role in the history of Sri Lanka’s North. Both then Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles and his brother, CIA head Allen Welsh Dulles, were descendents of Harriet Winslow, who had founded Uduvil Girls’ College in Jaffna. Anthropologist Gregory Bateson, who was instrumental in the CIA’s formation, had been stationed at the Kandy base of the CIA’s predecessor, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). However, as US-Sri Lanka relations expert Elliott L Watson once stated, “Ceylon’s international reputation was based primarily upon the knowledge contained on the packaging of boxes of exported Lipton Tea.”

Ceylon’s then government, despite a “middle way” rhetoric, had a pro-Western, anti-Communist stance; enjoying defence treaties with Britain, which held bases in Trincomalee, Katunayake and other places, including a Sigint station. The Governor-General, Army, Navy, and Air Force Commanders, were all British. British companies controlled the economy. The US controlled the Central Bank through its first governor, John Exter, and had also embedded its citizens in companies. It had even covertly supplied propaganda material to the United National Party UNP for the 1952 election. The US Navy found Ceylon’s ports invaluable for refuelling Korea-bound ships, and the Voice of America, with tacit government support, broadcasted anti-Chinese propaganda from there.

However, material aid was not forthcoming. As the ‘Korean War Boom’ — (which had boosted rubber exports — ended, monopolies kept rubber prices down, whereas import prices — especially for rice — remained high. The government spent huge amounts on the rice ration, provided to all at 25 cents per seer (kg). Meanwhile, China needed rubber. Minister R G Senanayake negotiated a Rubber-Rice Pact with China, which he saw as a counterweight to India. Ceylon became the only non-Communist Asian state to ship strategic materials to China.

Hartal

Nevertheless, because of the Rubber-Rice Pact, on the principle “our enemy’s friend is our enemy”, using the Battle Act, the U.S. sanctioned Ceylon — the only ally to receive such draconian treatment.

And so, the government faced huge budgetary constraints, causing Finance Minister J. R. Jayewardene to decide to hike rice prices. Consequently, the unions called a hugely successful ‘hartal’ (work-stoppage and closure of shops and offices), causing the government to seek refuge on board HMS Newfoundland and replace Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake with Kotelawela.

It was under these circumstances that Nixon undertook a visit to Ceylon. He had the mission of communicating U.S. disquiet about Ceylon’s relationship with China, and obtaining pledges of Ceylon’s commitment to the U.S.

The lead-up to Nixon’s visit did not lack drama either. Leila Palmer, wife of the recently-retired U.S. Embassy information officer Bruce Palmer, wrote a controversial, “exaggerated” article, for which U.S. Ambassador Philip Crowe ended up having to apologise personally to Kotelawala.

Impromptu Stops

During his stay, Nixon attended 15 official engagements, mainly to meet VIPs and business leaders. The night after his arrival, Radio Ceylon broadcast a recording by him, denying imperialist intentions. Nixon also made seemingly impromptu stops, such as one to greet people on the High Level Road; visiting a public market and even engaging with left-wing protesters against his visit. His wife Pat, who had the — then unique — task of being US “cultural ambassador”, attended several engagements on her own account, visiting orphanages, hospitals, senior citizens’ homes and also schmoozing with Colombo high society in a skillful exercise in public relations.

Eisenhower had set Nixon the task of portraying the US to the people of Asia as beneficial, reverent and compassionate, instead of the common perception as bullying, selfish and imperialist. Hence, Nixon ordered his staff to control public relations, tightly stage-managing carefully his appearances. He even ensured that, in a majority Buddhist country, nobody photographed him with a drink in his hand — a precaution ignored by the Buddhist Kotelawala.

Nixon’s most important engagement was a discussion with PM Kotelawela, which occurred on the very first day of his visit. This enabled Nixon, in a triumphant speech from the tarmac on his departure, to state that he had cleared up the misunderstanding over the Rubber-Rice Pact, and renewed the strong relationship between the two governments.

Aftermath

The Nixons returned to the US with a favourable opinion of their reception by both high and low society, and renewed optimism about the future. Kotelawela not only visited Washington the next year, but also turned down a Soviet offer to open diplomatic relations, and allowed U.S. aircraft to ferry French soldiers through Katunayake, to fight Vietnamese anti-colonial rebels. The US removed sanctions eventually, and increased aid to Ceylon.

For the American foreign policy establishment, the visit succeeded resoundingly. However, the deep divide between the poor majority and the rich, pro-western elite with whom Nixon interacted — including the so-called Purple Brigade — ‘the female political wing of the UNP… a swarm of social butterflies, endowed with beauty who fluttered around Sir John’ was further entrenched. This much-repeated error in U.S. foreign policy stemmed from an incorrect identification of hegemonic, often “Westernised”, elites with “the people”. Within three years, the Kotelawela government fell, relations with the US deteriorated, and a long-lasting friendship with China began.