Sigiriya is best known as an ancient rock fortress built by the parricide King Kasyapa more than a thousand years ago. The palace built on its summit once had at its entrance the figure of a gigantic lion, whose colossal paws are still visible. Sigiriya takes its name from this feature, for it literally means ‘Lion Rock’. The majestic lion figure, sedent like the Sphinx, evoked age-old notions of royal authority and the descent of the Sinhalese kings from a lion.

Reconstruction of Sigiri Lion Entrance and Palace. Sirinimal Lakdusinghe Felicitation Volume (2010)

The lion sculpture survived for centuries and was well preserved until at least the 9th century when we come across a reference to the ‘Lion Lord’ in a poem of that period. The poet tells us that he saw the Si-Himiya or ‘Lion Lord’ of Sihigiri, which so impressed him that he had no desire to look at the golden-complexioned damsel on the cliff.

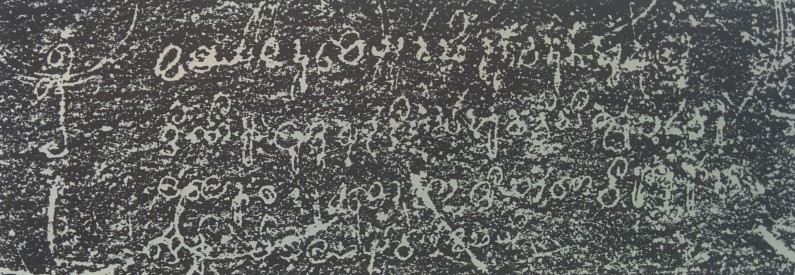

Our poet here was referring not to a woman of flesh, but to a painting on the rock wall, one of the numerous frescoes of beautiful women that a local Da Vinci painted a long time ago. His poem is one of over six hundred such graffiti inscribed on the Mirror Wall of Sigiriya dated to the eighth to tenth centuries. The poets drawn from all walks of life had some unusual names like Agboy, Mayli Boy, Tindi Kasub, Vajur Mihind, and Galagombu Mital, rather strange-sounding to modern ears.

Sigiri graffiti of 8th century. Sigiri Graffiti. Senarat Paranavitana (1956)

More interesting, however, is the wide range of topics they dealt with, covering all manner of things from love and jealousy to stormy weather and little-known customs of those times. They offer us a glimpse into their world which we can reconstruct from what little they left us-words inscribed on the Mirror Wall. The Wall takes its name from the belief that in the olden days, it was polished to such a high sheen that it reflected the frescoes on the rock wall opposite. The plaster, said to have been formed of crushed lime, egg white, and honey and polished with beeswax, still survives, along with the graffiti our poets left us. Here are six such verses with a story worth telling:

The Song of the Unknown Poet:

Aesimi dun hasun hasun seyin vil dut

Mula la ma saenaehi pul piyuman sey bamar dut

(Like geese who have seen a lake, I listened to the message given by her.

Like a bee who has seen full-blown lotuses, the bewildered heart of mine was consoled.)

This lovely couplet shows that the Sinhalese of old were great poets. They not only had a wonderful sense of rhyme and metre, but also resorted to a poetic device we call ‘play on words’ as we see in the combination of hasun (message) with hasun (geese). The poet’s eagerness to hear from his lady love is compared to the bee’s fascination for lotus blooms, whose large petals provide it an easy landing pad to drink its nectar and frolic if it wishes.

The Verses of the Wishful Voyeur:

Aedi sasa lapa se sukiduhu sad madala

Pavatu va dahasak ek savasak se menehi ma

(May you remain for a thousand years, like the figure of the hare the King of the gods painted on the orb of the moon, though that to my mind be like a single day)

Sri Lankans then, as now, saw a hare on the markings of the moon and not a man’s face as Westerners did. The belief has its origins in the Sasa Jataka story recounting the Buddha’s previous birth as a hare. The Bodhisattva, it is said, was a hare and prevailed on his animal friends to offer whatever food they could to those who were in need on the day before the full moon. To test him, the god Sakra appeared in the form of a Brahman and the hare offered itself to him for food. To commemorate this astonishing act of sacrifice, Sakra daubed the image of the hare on the surface of the moon. This is one of the many stories that explain the moon rabbit in Asian cultures.

The Chant of Lover Boy Agboy:

Nil katrola maleka aevunu vaetkola mala sey

Saendaegae sihi venney mahanel van ahoy ran vana hun

(Like a Luffa flower entangled in a blue Clitoria flower, the golden-complexioned one who stood with the lily-coloured one will be remembered at eventide)

Our poet is referring to the frescoes of the women on the rock, some of whom are depicted as fair-complexioned and others as dark-hued. He is comparing the fair lady standing by the side of a dark lass to a yellow Vätakoḷu (Luffa Acutangula) flower entangled in a blue Kaṭaroḷu (Clitorea Ternatea) flower. It seems he has a distinct preference for the fair damsel.

Many other Sigiri poets speak of becoming captivated by the golden-complexioned ones (ran-vanun) on the mountainside, who had long eyes (dig net) with breasts resembling young golden swans (tana rana hasu), and who had taken garlands of flowers in their rosy hands (surat athi mal dam). They are also described as heart-shattering fair damsels (la kol helillambuyun), and as radiant fair damsels whose lips are of the colour of the Bib creeper (vaela bib van lavan paehaepat helillambuyun). These suggest that the Sinhalese of medieval times generally preferred fair-complexioned women. However, preferences also depended on individual tastes. For example, a Sigiri poet named Kokeḷae Deva describes how a dark-complexioned one (sam vanak) had captivated his heart.

Fresco of Sigiri damsels to whom many of the verses were addressed. Image courtesy travelinsrilanka

The Boast of the Nameless Suitor

No helila me ki bithi dig netak

Mayi tepalan piyovur maejae kala la muka aerae nil taellak

(Did not the long-eyed one on the wall—the fair one—say to me

“Open your mouth and speak after having placed between the breasts a blue necklet”)

Here we have the poet’s lady love telling her suitor to speak no more till he makes her his betrothed by tying on her neck a marriage necklet known as taella. The tying of the tali as a symbol of marriage still exists among Tamil women, but this verse suggests Sinhalese women also had such a custom. In fact, this term survived until recent times. Benjamin Clough in his Sinhalese-English Dictionary (1830) gives taella as ‘a kind of ornament or gold collar worn on the neck or breast of women, particularly on the day of marriage’.

The Couplet of Sevu, Wife of Nidalu Mihid:

Mahanela bara varala gela huna pihira

La rasan aedini tama me baeluma sevataka vi apa nununagata

(This look of yours from a corner of your eye has been recognized by us as that of a co-wife- of you whose hair laden with blue water lilies combed stylishly drops down on your neck)

Lady Sevu here feigns jealousy for a pretty damsel on the rock face and uses the word sevata to address her. By this, she means a rival co-wife, since the word has its origins in the Sanskrit Sapatni ‘co-wife’. Polygamy was known in ancient India. The Rig Veda, for instance, compares a man attacked on all sides by his foes to a husband troubled by his jealous wives. The ancient Sinhalese also practiced it. The Mahavamsa refers to the five hundred women of the harem of King Devanam Piya Tissa. However, by the time Robert Knox wrote his Historical Relation of Ceylon in 1681, it was hardly, if ever, practiced, for he observes: “In this countrey each man, even the greatest, hath but one wife, but a woman often has two husbands, for it is lawful and common with them for two brothers to keep house together with one wife”.

Colonial times saw the practice outlawed once and for all so that in modern Sinhala, a mistress who is outside the law would simply be known as Hora Gaehaeni (rogue woman).

The Lines of the Lovelorn Loser

Aganini at salav me gi pohonnek neati da

Nava bag la sand minisak hu no vajanneyi

(O women, wave your hands though there be none who values this song. A man who has seen the young new moon of Bag should never be rejected)

The poet is suggesting that a man who had seen the new crescent moon of Bag (known in modern Sinhala as Bak-Maasa) should not be spurned by women, implying the ritual sighting of the moon had a Saturnalian character in the olden days. The Handa Balima, or ‘Looking at the Moon’ to usher in the Sinhala New Year in the month of Bak, may still take place. It did until very recent times. The ceremony involved looking at the moon for the first time after the dawn of the Sinhalese New Year. An earthen vessel was filled with water and folks beheld the image of the moon in the water.

Professor Vini Vitharana, in his little known work Sun and Moon in Sinhala Culture (1993), mentions a minor festival known as Maase performed in the southern coastal belt, between the towns of Matara and Tangalle, on the day of the New Year; which he believed to be the slowly disappearing vestiges of a once widespread lunar festival. The term is probably a shortened form of Maase Poya (New or Crescent Moon). Professor Vitharana notes that as soon as the new moon is sighted, it is customary for one to taste something sweet and look at a pleasant face, especially of a youthful female, which brings to mind the amorous words of our poet.

This seems to be the survival of an old Aryan custom. In ancient India Bhaga (the predecessor of the Sigiri Bag and modern Sinhala Bak) was the name of a solar deity who presided over love and marriage. Their Aryan cousins in Iran also had a similar deity known as Baga who seems to have presided over nuptials, as suggested by the Soghdian word for wedding — Baghani Spakte or Baga Union, — a union presided over by this deity. It also figures as the name of the month of Phalguna, in the form Bhaga-Maasa from which the Sinhala Bak-Maha takes its name. Curiously, the term is often associated with dalliance and sexual pleasure and also denotes the vulva or female sex organ, a construction of which bhaga-mani (‘Jewel of the vulva’ or ‘gem of pleasure’) is applied to the clitoris in Sinhala.

Thus it is possible that in the olden days, the Sinhala New Year, besides being a festival dedicated to the Sun and the bountiful harvests it gave, was also a lunar festival centred on a now obscure fertility cult.

The Sigiri Poets, through their graffiti, left us a veritable time capsule, through which we could reconstruct the times they lived in with some certainty. If poetry is the expression of one’s world with a few words, then our Poets certainly achieved that with the few lines they left us.

Cover image courtesy Pixabay