Sri Lankans are not really known for their stature—the average local male is 5 feet 4½ inches, or 163.6 cm tall. But tens of thousands of years ago, a group of people existed on this island who, if they were to stand side by side next to an average Lankan family today, would tower over them (more or less). Known as the Balangoda Man, this ancient hominid stood at roughly 174 cm in height (females were around 166 cm tall), was made of strong bones, and possessed a thick skull, heavy jaws, and large teeth, painting a picture that couldn’t be more different from the modern day MC dude.

Balangoda Man (Homo sapiens balangodensis) was an anatomically modern, early human who lived in the Mesolithic era, and was named after the archaeological sites near Balangoda, where skeletal remains of this enigmatic being were first discovered.

Skeleton of Balangoda Man excavated in Bellanbandi Palassa in the 1950s. Image courtesy archeology.lk

Origins

Though modern humans (that is, homo sapiens) have existed on the island since at least 125,000 BP (before present), the prehistoric record of Sri Lanka becomes much clearer and more complete from about 34,000 BP, with stronger evidence of human settlements obtained from cave excavations in the lowland wet zone. These prehistoric humans are broadly categorised as belonging to the Balangoda cultures.

According to historian K. M. De Silva, in the Mesolithic phase, the Balangoda cultures were found throughout the island, with rudimentary knowledge of agriculture in the Neolithic phase. Balangoda Man also knew how to produce fire. However, De Silva believes that the scarcity of calcined bones among his food remains suggests that flesh was generally eaten raw. There is a hint of cannibalism, too. Former Director of Archeology, S. U. Deraniyagala, posits that Balangoda Man consumed every conceivable type of animal, from rats, snails, and small fish, to snakes and even elephants. The robustness of their skeletal remains indicates that this was, in fact, a well-balanced diet.

Tool Use

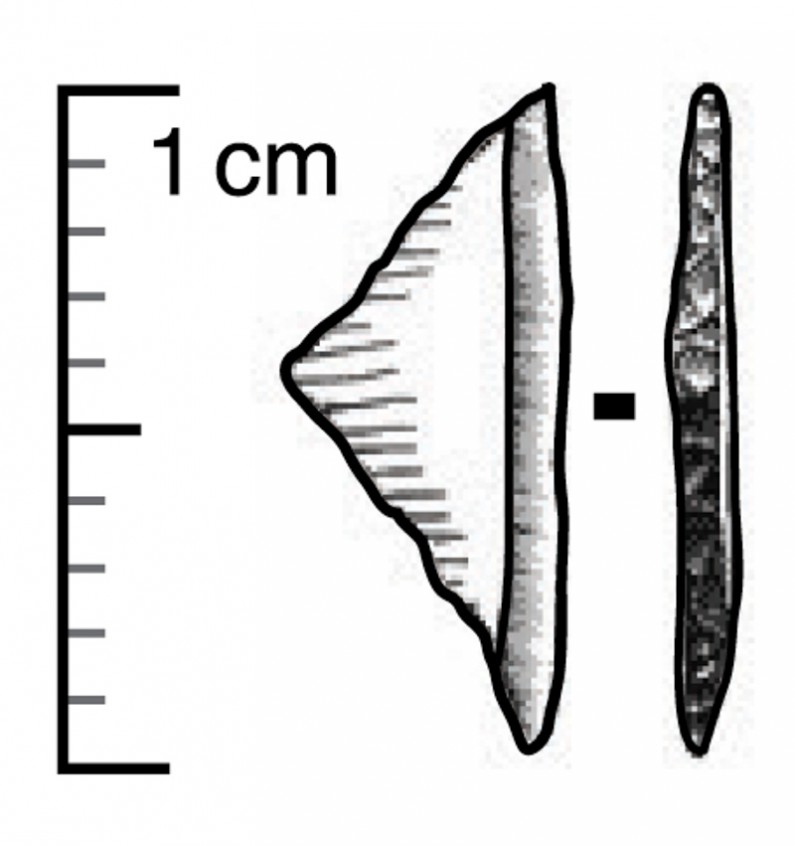

Geometric microliths—these were among the many tools used by Balangoda Man. Image courtesy Serendib (BT Options)

Balangoda Man was also known for his innovative use of tools—from microliths and hand axes (made of elephant bone) from the Meso-Neolithic era discovered in Bellanbandi Palassa, to daggers carved out of sambar antler. Cultural discoveries such as ornamental fish bones, beads made of sea shells and shark vertebra, sea shell pendants, carbonised wild banana, and polished bone tools have also been made. The frequency at which the marine shells, shark teeth, and shark beads occurred at the different cave sites have led archaeologists to believe that that the prehistoric man in the hinterland had direct contact with the coast, located well over 40 km away.

Settlements

The earliest evidence for anatomically modern human settlements comes from the Fa Hien cave, named after the famed Chinese monk explorer Faxian, who visited the island in the fifth century AD. Other evidence has also been found at Batadomba-lena near Kuruwita (28,500-11,500 BP), Belilena at Kitulgala (over 27,000-3500 BP), and Alu-lena at Attanagoda near Kegalle (10,500 BP). This data, obtained by radiocarbon dating, is supplemented by those from the open-air site of Bellanbandi Palassa near Embilipitiya, dating back to 6,500 BP.

According to Deraniyagala, these human remains have been subjected to detailed physical anthropological study. “These anatomically modern prehistoric humans in Sri Lanka are referred to as Balangoda Man in popular parlance (derived from his being responsible for the Mesolithic ‘Balangoda Culture’ first defined in sites near Balangoda),” he writes.

Link To The Veddas

Deraniyagala also points out in his research that the genetic continuum, from as far back as 16,000 BP to the present day Vedda population, is “remarkably pronounced.”

Their unusual (for Sri Lanka) stature and robust bone structure, among other traits, have survived in varying degrees among the Vedda population and some Sinhalese groups, leading Deraniyagala to theorise that Balangoda Man was a common ancestor of both peoples.

However, he dismisses the idea that the Balangoda Man was a homogenous race. There would have been unimpeded gene-flow between southernmost India and Sri Lanka (in both directions) from the Palaeolithic onwards, and Deraniyagala believes that future research will reveal a range of genetic clusters in the prehistoric populations of this region. This, he says, would invalidate the concept of Balangoda Man as a homogeneous race.

If you’re wondering how these migrations to and from the Indian mainland were possible, the continental shelf shared between Sri Lanka and India has only been fully submerged below the Palk Strait and the Adam’s Bridge since around 7,000 years ago. At just 70 m in depth, significant reductions in sea level due to climate change, in at least the past 500,000 years, periodically caused the continental shelf to be exposed, forming a land bridge approximately 100 km wide and 50 km long. It was last submerged in 7,000 BP, after which all the fauna species that had migrated to the land now known as Sri Lanka (including elephants) evolved in isolation, until human settlers found their way here again by boat, thousands of years later.

It is believed that there is a direct link between Balangoda Man and present day Vedda populations. Image credit: Roar/Christian Hutter

Even if Balangoda Man wasn’t a homogenous race, Deraniyagala finds him a useful working concept when referring to Lankan humans from the late quaternary era. According to his findings, Balangoda Man settled in virtually every corner of Sri Lanka—from the damp and cold high plains such as Maha-eliya (Horton Plains) to the arid lowlands of Mannar and Wilpattu, to the steamy equatorial rainforests of Sabaragamuwa.

Their camps were invariably small, rarely exceeding 50 sq. m in area, which, Deraniyagala believes, suggests that they were occupied by not more than a couple of nuclear families at most.

“This lifestyle could not have been too different from that described for the Veddas of Sri Lanka, the Kadar, Malapantaram and Chenchus of India, the Andaman lslanders and the Semang of Malaysia. They would have been moving from place to place on an annual cycle of foraging for food. The well-preserved evidence from the caves and Bellanbandi Palassa indicates that a very wide range of food—plants and animals—were exploited. Among the former, canarium nuts, wild breadfruit and wild bananas are prominent.”

Batadomba Lena, another site where skeletal remains of Balangoda Man was found. Image credit: Serendib (BT Options)/David Blacker

K. M. De Silva, too, finds links between Balangoda Man and the Vedda population. In physical characteristics, he writes, Balangoda Man was predominantly Australoid with Neanderthaloid overtones, and the Vedda aborigines of Sri Lanka are physically closest to Balangoda Man from among the ethnic groups who still live on the island today. (Australoids have the second largest brow ridges, and Balangoda Man’s robust structure was probably due to his Neanderthal traits).

Decline

As more Indian settlers began to find their way to Sri Lanka, prehistoric man had to make way, and gradually declined in number. “The submergence of Balangoda Man and his physical and cultural attributes under pressure of the early colonisers from India would very likely have post dated 500 BC, with possible survivals into a much later period in the rainforests of Sabaragamuwa, which were not penetrated by civilised man to any considerable extent until the end of the first millennium AD,” writes De Silva.

Thus, Balangoda Man was forgotten in the annals of history, until relatively recent archaeological discoveries brought him back into the limelight. If you feel like paying your respects to him, there is a section at the recently renovated Colombo National Museum dedicated to this ancient ancestor of ours. It’s well worth a visit.