In March 2018, the magazine Nature Communications published an article by a team of archaeologists from Exeter University. The team had been investigating possible ancient settlements in the Amazon’s upper Tapajós Basin, using a variety of modern techniques, including satellite imagery. They discovered 81 sites from the pre-Columbian era (about 1250-1500 A.D.).

The remnants of several hundred ancient villages had been discovered before, but this finding indicates the existence of a widespread and highly populous civilisation in Amazonia, previously thought to have been an almost untouched jungle area, sparsely inhabited by a tiny nomadic population. Significant parts of the soil of the vast rainforest appear to have been mulched and composted with waste to create so-called fertile “dark earths”, or terra preta.

Extrapolating from the available information, the team predicted that 1,000-1,500 similar settlements must be scattered over 400,000 hectares of the southern rim of the Amazon, in which between 500,000 and a million people must have lived before the arrival of Europeans and the diseases they brought which devastated the population.

Fawcett

The discovery of this ancient civilisation has been very much a 21st century affair. Previously, the received wisdom held that the Amazon basin, considered a pristine and impenetrable rainforest, populated by a few savage Indios, could in no way host any civilisation. The man ultimately responsible for changing that opinion, British geographer, artillery officer, cartographer, and amateur archaeologist Colonel Percival Harrison (“Percy”) Fawcett, disappeared in 1925 on a mission to discover what he termed “The Lost City of Z”.

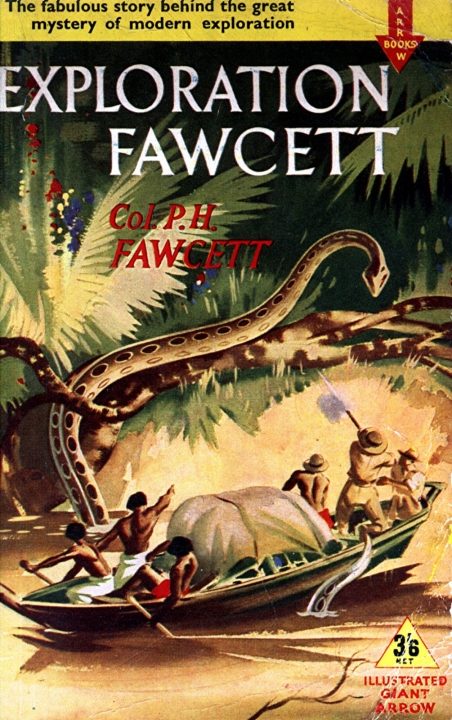

Shooting the giant anaconda, the cover of Expedition Fawcett, written by Brian Fawcett

Fawcett first went to South America in 1906 in order to map the border between Brazil and Bolivia, which the Royal Geographical Society, to which he belonged, had been commissioned to do as an unprejudiced third party. He made several more expeditions into the Amazon area, in the course of which he shot a 19-metre anaconda and discovered the Double-nosed Andean Tiger Hound.

By 1914, apparently based on manuscript documents written by an anonymous 18th century Portuguese explorer, he formulated a theory that a complex civilisation had flourished in Amazonia in pre-Columbian times, and that a lost city, which he named “Z” (Zed), existed in the Mato Grosso region of Brazil. In 1925, accompanied by his elder son Jack and one of Jack’s childhood friends, Raleigh Rimell, he set out on that final expedition to locate the city.

Disappeared

Several expeditions over the years set out to find what happened to Fawcett, with no tangible result. Legends grew about his disappearance, that he had founded a new religious community in the depth of the rainforest, that he had “gone native”, and so on. At least one report mentioned Fawcett as being alive, and Jack married with two blonde, blue-eyed children.

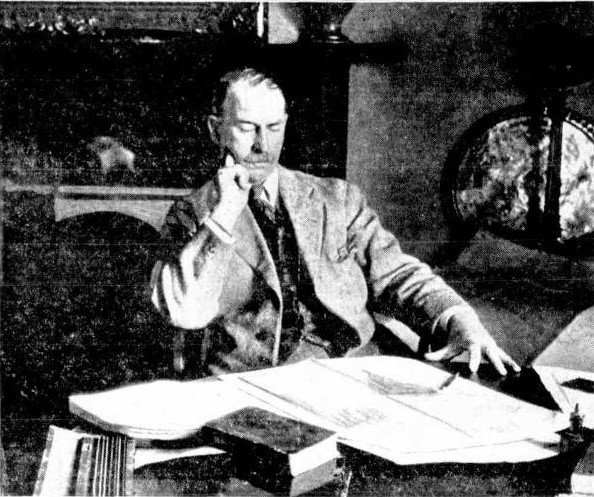

Percy Fawcett planning expedition. Caption: Percy Fawcett planning his expedition in his Devon study. Image courtesy National Library of Australia

His fame inspired the Belgian cartoonist Hergé to create a fictional British explorer, Ridgewell, who appeared in the graphic “Tintin” novels The Broken Ear and Tintin and the Picaros. With his steely-blue eyes and iconic stetson hat, he has been mentioned as a partial inspiration for the fictional archaeologist-adventurer Indiana Jones. His story also inspired Sherlock Holmes’ inventor Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, Evelyn Waugh’s A Handful of Dust, (both books were later made into films), and the Bing Crosby/Bob Hope comedy The Road to Zanzibar.

In the early years of this century, David Grann, an American journalist writing for the New Yorker, ventured into the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso in search of Fawcett. In 2005, he published his findings in an article, which he later expanded into a book, which provided the basis for the 2016 film The Lost City of Z.

Poster for the film lost City of Z. Image courtesy Wikipedia

In his book, Grann reported on the findings of Anthropologist Michael Heckenberger of the University of Florida, who had teamed with the local Kuikuro people in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso to uncover 28 towns, villages and hamlets that may have supported as many as 50,000 people. Grann concluded that these discoveries matched Fawcett’s claims.

Science Fiction and Theosophy

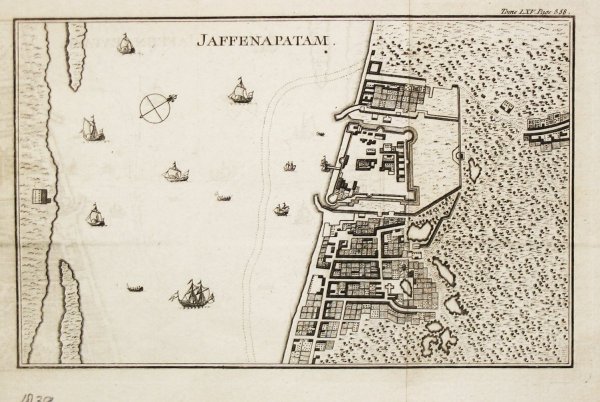

Fawcett, born in Devon in 1867, lost his father, Indian-born army officer and cricketer Edward Boyd Fawcett when only 17. He joined the Royal Artillery, in which he learnt surveying, and found himself posted to Fort Frederick, Trincomalee in 1886.

Sri Lanka would not have been totally unfamiliar to him. His brother, science fiction writer, chess player, racing car driver, aviator and mountain climber Edward Douglas Fawcett, had joined the Theosophists, helping edit Madame Helena Petrovna Blavatsky’s The Secret Doctrine. He came out East and settled in the Theosophist headquarters at Adyar, Chennai.

Edward Douglas Fawcett. Image courtesy Theosophy Wiki

Edward wrote prolifically, as E. Douglas Fawcett or E. D. Fawcett, his works including three science fiction books in which he predicted air raids and tank warfare, and―significantly, in the light of what happened later―wrote of a hollow earth. He also published numerous theosophist articles, notably A Talk with Sumangala – Is Southern Buddhism Materialistic?, published in the journal Lucifer in April 1890: he had taken Pansil and accepted Buddhism.

Percy Fawcett may also have accepted Buddhism. Certainly, he became an ardent spiritualist and follower of Madame Blavatsky, and his belief in the lost Amazonian civilization may have stemmed in part from a belief in a portal to the hollow centre of the Earth.

Treasure and Romance

In Sri Lanka, Percy Fawcett had a lot of spare time, most of his administrative tasks, apart from inspecting his guns and his section of the fortress walls, being carried out by the non-commissioned officers under him. Shunning the usual pastimes of a British officer, such as drinking, gambling and sex with the natives, he set out to explore the country. He discovered an inscription on a rock, which he copied and which apparently said that treasure lay beneath the rock. Unfortunately, he never found the rock again, but the incident served to whet his appetite for treasure hunting and exploration.

In 1888, in Galle, he met Nina Agnes Patterson, born in Kalutara in 1871, recently returned to Sri Lanka after completing her education in Scotland. He found her not only beautiful, but intelligent, with strident views about women’s rights. He fell in love with her.

Nina’s father Judge George Watson Paterson, who gained some fame as a philosopher, gave him some documents relating to a treasure buried in cave beneath some rocks known as “Gala-pita-gala” (rock-upon-rock) near Badulla. Paterson claimed to have received the documents from a Kandyan chieftain. In 1888, Fawcett set out to look for the treasure, and received some gold bricks from wandering Veddas. However, he found no treasure. Returning to the spot five years later, a white cobra stopped him.

In 1890, he proposed to Nina and she accepted. However, his family objected to her, for reasons unknown; her mother may have been a half-caste. His family told Fawcett (falsely) that Nina had lost her virginity. Appalled, he broke off the engagement. Nina returned with her father and sister to England. In 1897, she married another Army officer, Herbert Christie Prichard, a former aide-de-camp to the governor of Queensland. However, he died in Alexandria within a few months, telling her that Fawcett was her true life partner.

Jack

Fawcett received a posting back to Britain and, having learnt that Nina had, in fact, been a virgin before he met her, wrote and asked her to restart the engagement. She consented and

in 1901, they were married in Richmond, with George Paterson and E. D. Fawcett as attesting witnesses.

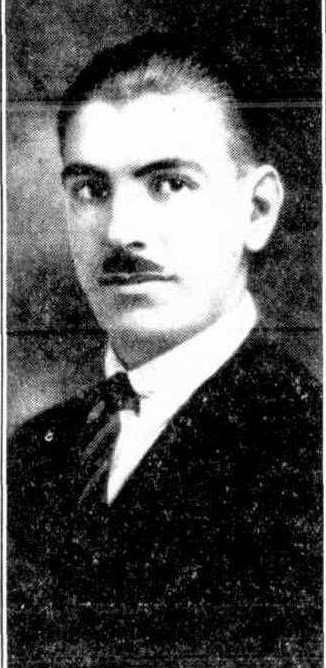

Jack Fawcett.jpg. Caption: Jack Fawcett. Image courtesy National library of Australia

The couple returned to Sri Lanka, and in 1903 Nina gave birth a son, whom they named Jack―apparently a name of some significance, being the nickname of Madame Blavatsky. According to Fawcett, a deputation of Buddhists and soothsayers visited him before the birth and predicted that the child would be born on 19 May, Vesak day, a reincarnated “advanced spirit”, would possess a mole on his right foot, his toes would descend in size in pairs, and he would have a slight squint. This all happened as foretold, and crowds lined the streets to see the new-born wonder. A second son, Brian, and a daughter, Joan, were born after the couple returned to Britain, but neither of them had Jack’s significance to Fawcett.

Jack remained proud of his connection to Sri Lanka. “I begin to look upon Ceylon as almost my own private property now,” he wrote to Harold Large, a New Zealand spiritualist and former theosophist, just before the final expedition, “and feel quite annoyed to think that there are strangers laying down the law there.”

Secret Papers

He also mentioned that Raleigh Rimell intended to join him in Sri Lanka later, and that his participation in the Amazonian expedition was to prepare him for the Sri Lankan one. The Fawcetts aimed, it appears from papers in the possession of Joan Fawcett, access to which she provided to playwright Misha Williams, to establish contact with higher beings in Amazonia and Sri Lanka. The search for the lost Amazonian city would facilitate this.

Raleigh Rimell_fawcett.jpg. Caption: Raleigh Rimell. Image courtesy National Library of Australia

These “secret papers” reveal that spiritualism and the occult had an extraordinary influence on Fawcett. He appears to have met Large through an organisation known as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. The celebrated magician and occultist Aleister Crowley, another member of this order, who associated with Large, who visited Sri Lanka in 1901, may have known him; after Fawcett’s disappearance, Nina went to see Crowley in Cannes. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, mentioned above, also belonged to the order.

Fawcett’s second son, Brian, wrote that his father’s 1905 autobiographical essay “At the Hot Wells of Konniar” gave a vital clue to his life. The essay describes a night Fawcett spent in a grove near the hot springs, under the influence of a powder given him by a Sri Lankan “fakir”, during which he saw a vision which told him what to do in the future.

Kanniya hot springs today. Image courtesy K. Shayanathan, Wikipedia

So it appears that his Sri Lankan experiences fuelled Fawcett’s obsession. That obsession led to his disappearance, the publicity surrounding which nourished the idea of a lost Amazonian civilisation. The many archaeological findings which have emerged from the Amazon basin may not match early 20th century imaginings of what the ancient South American civilisation should have looked like. There are no vast stone structures, no pyramids or ziggurats. However, they do shed much light on how human cultures developed in the Americas. The rich archaeological findings which are re-shaping our thinking about pre-Columbian Amazonia may never have been possible without that obsession, to which Sri Lanka’s cultural heritage was crucial.

Cover image – The Lost City Of Z (2017). Image courtesy: FilmFed.com