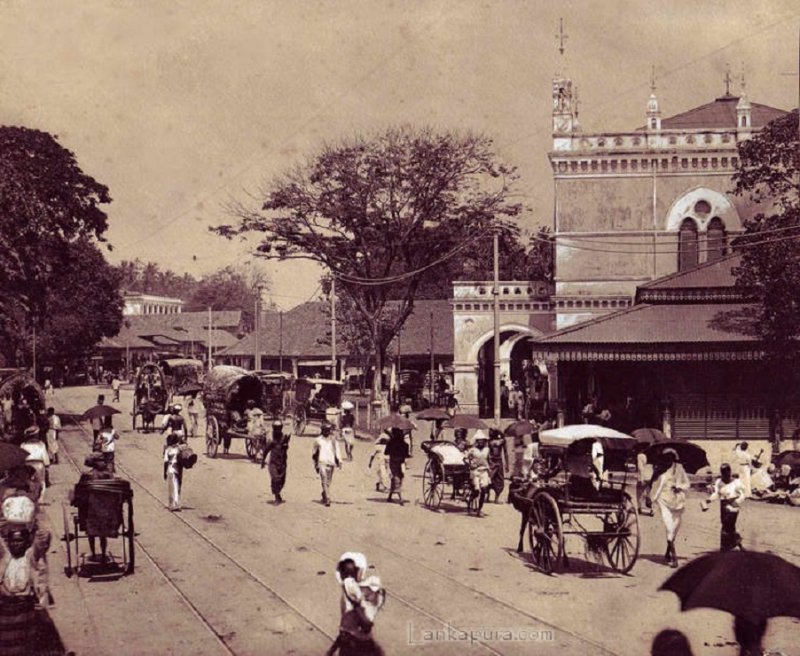

Colombo Fort has, for over a century, been the centre of Sri Lanka’s economic activity; and being strategically located to facilitate international travel, it is not surprising that colonisers, be it the Portuguese, Dutch, or the British, chose to consolidate their control over the city. More than seven decades since the last of the colonisers departed, relics of a bygone era still dot the landscape of Colombo Fort, albeit in the more innocent and harmless form of buildings.

These buildings that were once gleaming representations of someone’s success may have since fallen victim to the passage of time or — less romantically — the heavy artillery attacks by the battalions of pigeons and crows that roam the city. None of this, however, can erase the fascinating histories behind the buildings.

The Central Point Building

Though Colombo may now be home to many tall, sometimes imposing, concrete megastructures, it was the Central Point Building that long ago claimed the title of the tallest structure in Colombo. Situated right behind the Dutch Hospital on Chatham Street, the building is now home to the Economic History Museum of Sri Lanka.

The building, with its beautiful Greco-Roman architectural style, was declared open to the public in 1914 and took nearly four years to build. Back then, it was known as the National Mutual building since its main tenant was the National Mutual Life Association of Australasia Limited — a pan-Asian insurance giant at the time.

The building was heavily damaged by the Central Bank bomb blast in 1996 and was left abandoned for some time. It was later used by the Sri Lanka Army as a makeshift barracks before being bought over by the Central Bank in 2011. After painstaking renovations, the building was reopened in 2013 and was designated as the home of the Economic History Museum of Sri Lanka.

Funnily enough, the name Central Point actually refers to the Chatham Street Clock Tower or the Old Colombo Lighthouse located nearby, which is considered the ‘Central Point’ i.e. starting point of the country’s road network.

The New Chinese Shop and the Lalchands Building

Chatham Street was also home to two very special, and historic establishments that were sadly lost to development.

One was the Lalchands building, which was one of the very few buildings in the country that displayed real Dutch heritage, with its history going as far back as 1815.

The other was the ‘New Chinese Shop’, which was owned by a certain Win Lee Chang who hailed from one of the many Chinese families that have lived in Colombo for generations. The shop is believed to date back almost 200 years and once functioned as a residential space, nurse’s quarters, and a goldsmith’s before eventually being converted to a shop that sold school uniforms.

The Olcott House

Located at 54, Maliban Street is a two-storied house that was once the abode of American military officer Colonel Henry Steel Olcott, one of the major revivalists of Buddhism in Sri Lanka.

The house, which was constructed according to the Dutch architectural tradition, is believed to have been built sometime between 1881 and 1885, after Olcott arrived in Sri Lanka on 16 May 1880. On 1 November 1886, Olcott set up a small English Buddhist school at his house with 37 students in attendance. As the number of pupils began to increase, the little school moved to Prince Street before finally finding its permanent home in Maradana as Ananda College.

In 2005, the Ministry of Cultural Affairs and National Heritage decided to renovate and preserve the building, which is now considered a protected structure of archaeological value.

The Gafoor Building

Located on the corner of Sir Baron Jayatilaka Mawatha and Leyden Bastian Street in Colombo Fort, the Gafoor Building is perhaps the Flatiron building’s portly, pot-bellied Sri Lankan cousin.

The building is believed to have been commissioned more than a century ago by Noordeen Hajiar Abdul Gafoor, one of the most high-profile jewellers and gem merchants of his era. Having built a reputation as a fine jeweller by exhibiting Sri Lankan gemstones to King George V and elsewhere around the world, Gafoor wanted a beautiful building to house his jewellery emporium in. Once construction was completed in 1915, space was also rented out to prominent business houses such as H. W. Cave & Co, Mackwoods Ltd, Holland-Ceylon Commercial Co., and the Rubber and Produce Traders (Ceylon) Ltd.

As Colombo changed, so did the Gafoor building’s fortunes. Despite being declared a protected monument under the Antiquities Ordinance, the building was literally falling apart before the Urban Development Authority acquired it with the intention of converting it into a 63-room city hotel. When last checked, renovations were still ongoing.

The Cargills-Millers Building

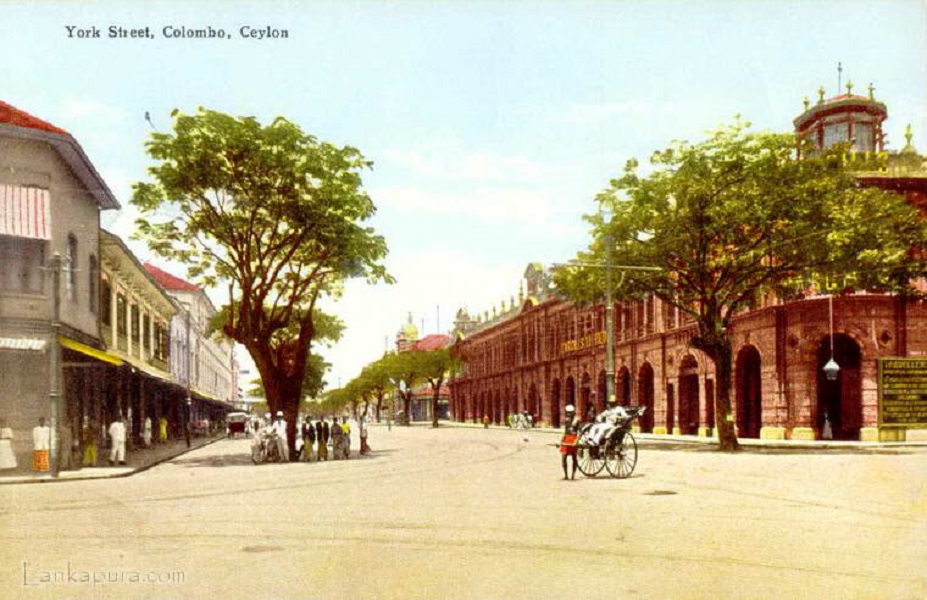

This unmistakable brick-red building on York Street has a long and colourful history of its own that dates back to the Dutch occupation of Ceylon. The site of the building originally housed the residence of Peter Slusken, the Commandeur of Galle in 1788. Later, the British administration acquired Slusken’s home so that it could be used as the residence of Governor Frederick North. A few decades later, the land fell into the hands of William Milne and David Sime Cargill, who were successful business partners. The two originally set up their business in Kandy and as it flourished, later decided to occupy a space at York Street.

William Milne retired to Glasgow in 1896 and Cargill took over the business and incorporated it as a limited company. The company grew so fast that by 1909, it is said to have employed an executive staff of 32 Europeans and 600 workers.

In the mid-1940s, Sir Chittampalam A. Gardiner made a bid for and successfully acquired the business. Following the completion of the sale, Cargills (Ceylon) Ltd. came into existence as a Public Limited Company on 1 March 1946. In 1981, the Ceylon Theatres Group became a controlling shareholder and laid the foundation for Cargills to become the company we all know today.

The Cargills-Millers building, which bears a slight resemblance to the iconic Harrods building in London, was declared open in 1906 after a four-year-long construction process. The building was designed by Edward Skinner and built by Walker Sons and Company, the same company behind the construction of other iconic buildings in Colombo such as the Galle Face Hotel.

P.S. Walker Sons and Company exist to this day as the troubled MTD Walkers PLC. According to a 10 November 2020 Daily Mirror report, the company had a Rs. 3.4 billion hole in its balance sheet.

The Grand Oriental Hotel

Built during the British occupation of Ceylon, the Grand Oriental Hotel was considered to be one of the finest luxury hotels at the time in this part of the world.

The land on which the hotel now sits was originally the site of a single storey building occupied by a Dutch Governor. From the late 1830s to the early 1870s the site was home to a barracks for the British Army.

Later, Governor Sir Robert Wilmot-Horton decided to convert the existing structure into a hotel. Architect J.G. Smither from the Public Works Department, who was also responsible for the design of the National Museum and the old Town Hall, was contracted to design the new hotel. It was estimated that construction would cost 2,007 pounds, but Governor Norton managed to complete the project in a year at a cost of only 1,868 pounds.

On 5 November 1875, the Grand Oriental Hotel of Colombo was declared open. Guests were able to choose from 154 luxury and semi-luxury rooms. Due to its location, which is in close proximity to the Port of Colombo, the hotel was often the first establishment travellers set foot into after stepping off the ships they arrived on. This review from 1907 makes it aptly clear why the hotel proved to be popular with visitors to Ceylon:

“The Grand Oriental Hotel (or GOH as it is familiarly known far and wide) was the first of the modern type of imposing hotels erected in the East. With its towering front facing the harbour and the shipping and its main portico separated by only a few yards from the principle landing stage, it occupies both a commanding and convenient position; and passengers by the mail steamers who are passing through the port are especially catered for at this establishment in the very best style… The building contains 154 bedrooms… The hotel is lighted throughout by electricity and all the public rooms and bedrooms are kept cool by means of electric fans.”

In 1966 Geoffrey Bawa was asked to remodel the hotel, and the architect ended up being the brains behind the popular Harbour Room, a restaurant on the fourth floor of the hotel that directly overlooks the Colombo Port. Bawa was instrumental in restoring most of the hotel’s original glamour, which had disappeared due to decades of neglect and poorly-thought-out modifications. The hotel was also home to Sri Lanka’s first nightclub, the Blue Leopard.

In its present state, the hotel consists of 80 rooms and two suites. The suites are named after two famous people who stayed at the hotel. One of them was writer Anton Chekhov, who stayed at the hotel in 1890 for five days, during which time he started writing the short story Gusev.

The Republic Building

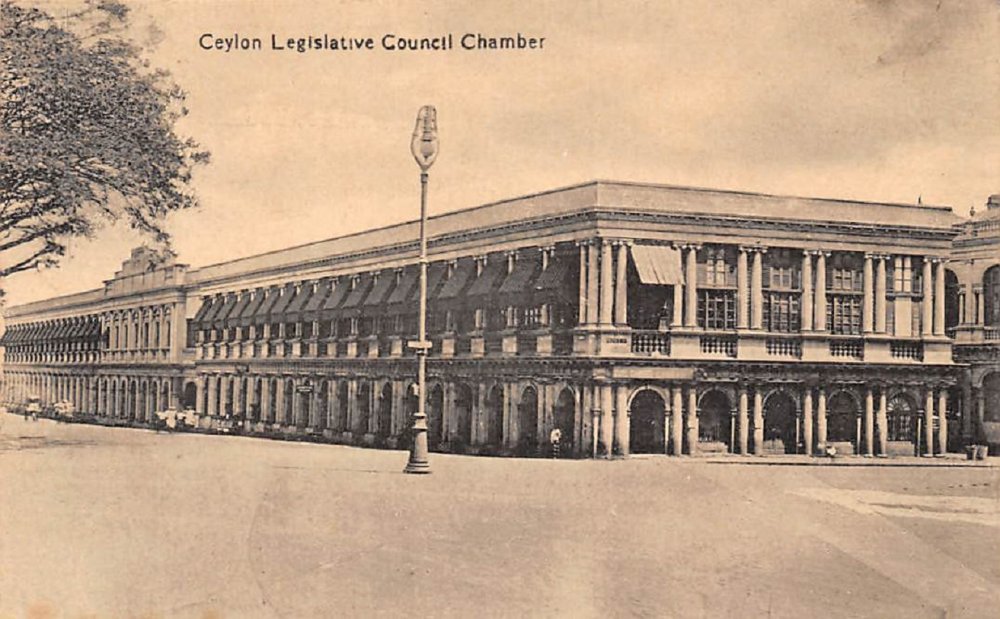

Towards the end of Janadhipathi Mawatha is a stately white building that now houses Sri Lanka’s Ministry of Foreign Relations. This building, though now known as the Republic Building, was known as the Senate Building until 1972, and was constructed during the British colonial era to house the Legislative Council of Ceylon. The British administration had to demolish an old Dutch building to make way for the Republic Building, whose new design called for two porticos down the middle with two long corridors on both sides.

After the Legislative Council was given a new home in the form of the Old Parliament building near the Galle Face Green, the building has periodically been home to the Senate of Ceylon, the Prime Minister’s Office, the Cabinet Office and the Ministry of External Affairs and Defence. After the Ministry of External Affairs and Defence was split into two distinct ministries, the building has continued to house the Ministry of Foreign Affairs/Relations since 1977.

The building was renamed the Republic Building after Sri Lanka became a Republic in 1972.

A rich history that dates back hundreds of years has given Colombo the chance to lay claim to some of Asia’s finest, most beautiful, and architecturally significant buildings. As such, it would be good to see the city modernise in harmony with this rich architectural legacy, rather than jeopardise Colombo’s interesting atmosphere of old-meets-new with short-sighted, unchecked development that could potentially turn into an eyesore over the years.