Gender disparity in the science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) disciplines is an issue often talked about today, even as a number of initiatives worldwide, (GirlsWhoCode, TeachHerInitiative and GlamSci among them) work to bridge the gap.

In Sri Lanka, there are still not nearly enough women enrolling in the STEM fields, a 2017 UNESCO report finding that gender stereotypes and biased attitudes compromise the quality of the learning experience for female students, limiting their education choices.

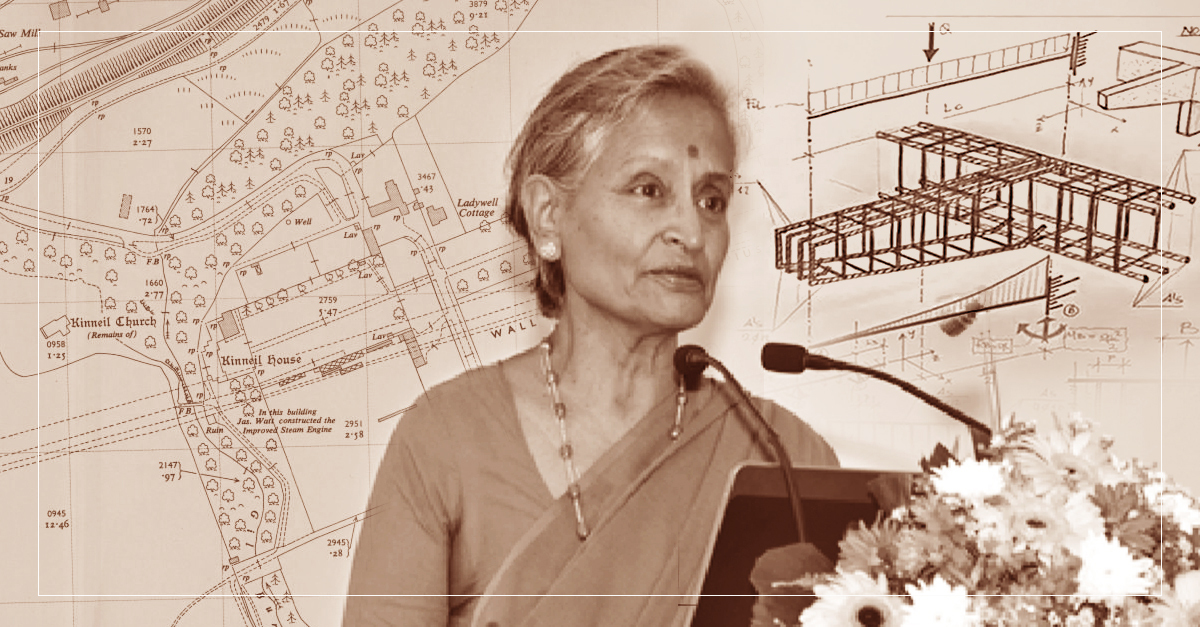

At such a time, the work of a few pioneering women in these fields is of great value. Dr. Premala Sivaprakasapillai Sivasegaram—the first female engineer of Sri Lanka, is one of them.

Getting Into It

Dr. Sivasegaram’s father was an engineer, “[and] both my brothers did engineering,” she told Roar Media. Dr. Sivasegaram herself was interested in dancing, but her father didn’t think it was a good idea. “It was a very competitive field and [engineering] doesn’t involve that,” she said.

Her father, who worked as an engineer at the Colombo Port, moved his family to Jaffna in February 1942 after Malaya and Singapore fell to the Japanese during World War II, and it became evident that an attack to Ceylon was imminent.

Dr. Sivasegaram was born on April 22, 1942 at grand-uncle’s house within the Jaffna Fort, but returned to Colombo in June after the Japanese threat had receded.

In Colombo, Dr. Sivasegaram studied at Ladies College, where she was a bright student, who enjoyed music and dance from the tender age of three, and danced so well that she was included most year-end school events.

She was also one of just two girls who followed the mathematics stream at Ladies College. Dr. Sivasegaram entered the Engineering faculty in 1960.

Learning Engineering

Many people were opposed to Dr. Sivasegaram joining the Engineering Faculty of the University of Ceylon, questioning her ability to get traditionally male-dominated metal casting and welding work done.

She also recalls that the university administration itself was not very friendly towards her when she entered the Engineering faculty in 1960.

“The Dean was not very keen [to have me],” she said, quite frankly. “He said, ‘once the girls come they will study harder than the boys and take their places. Then they’ll get married and not work. So the boy will lose his living’. That kind of fear was there…Mostly conservative society [I suppose] at the time.”

Dr. Sivasegaram said the Dean of the University of Ceylon even asked her father—who was then a member of the Faculty—to stop her. “[But] my parents didn’t stop me,” she said.

At the time, the Engineering Faculty at the University of Ceylon was known as the ‘Takaran Faculty’, because it was a bare bone building with ‘takaran’ or metal roofing sheets. This was where Dr. Sivasegaram attended lectures, drawing classes and surveying, while all other practicals, were conducted at the Ceylon Technical College in Maradana.

She recalled that she had no trouble at all amongst her peers in the Engineering faculty, and that her batchmates were friendly and helpful towards her. “Only the carpentry baas wouldn’t help me,” she said with a laugh.

Having done her practicals the hard way, she found her experience allowed her to have a very thorough hands-on knowledge of her work—something that helped her immensely in her career later on.

Sivasegaram passed out as Sri Lanka’s first female engineer in 1964. She was followed by Sumee Munasinghe—who studied electrical engineering—in 1966, and Indira Arulprakasam ten years later, in 1977, who passed out as a mechanical engineer, and went on to become the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Alberta, Canada.

Furthering Her Education

After passing out, Dr. Sivasegaram was appointed an instructor in the Engineering Faculty of the University of Ceylon, Colombo. This was around the time the Engineering faculty was moved to Peradeniya, and Dr. Sivasegaram assisted in setting up the Fluids Lab equipment.

As public service was compulsory at the time, Dr. Sivasegaram was next posted to the Public Works Department (PWD), where she worked for a few months before taking up the Ceylon Government University Scholarship to Somerville College, Oxford to pursue a doctorate.

“I never expected that scholarship,” she said. But once I got that I decided to go immediately. “

Her experience in the UK opened up many opportunities to her—she even attended the International Conference for Women Engineers and Scientists in Cambridge in 1967, where she was chairwoman for one session.

After her three years on scholarship (1965-1968), she worked at the Central Designs Office of the British Ministry of Public Building and Works. It was in the UK that she met her future husband, who was also in London on a scholarship from the Faculty of Engineering, University of Ceylon.

“We got married in December 1968,” she recalled. “I continued to work even after having a baby. [And] the Public Services Commision kept asking me when I was coming back. Because it was compulsory service!”

Dr. Sivasegaram eventually returned to Sri Lanka in April 1970, with her son who was six months old.

“I thought that I would like to stay at home for another 6 months. But I was told that the fine was Rs. 150 a day if I didn’t go to work. So I went to work at the Kandy Peasantry Commision for a salary of Rs. 500 a month,” she said.

She also felt that not working after becoming mother “would have looked bad, being the first woman engineer,” but admits wistfully, that she would have liked to have spent a little more time with the baby.

Back To Work

Dr. Sivasegaram found, that despite fears people had on her behalf, she had no problems with the staff at the Kandy Peasantry Commission accepting her as an engineer.

“The labourers never gave me [any] problems,” she said, adding that the men only found it unusual to have a woman supervising them, but were never “rude or anything.”

But Dr. Sivasegaram had high expectations for herself. She recalled to the Silumina newspaper, “Perhaps it was the Dean’s fears about women taking up engineering and then abandoning it that made me feel that I must not say ‘no’ and must never take refuge in being ‘a woman’ and refuse to take certain jobs.”

So Dr. Sivasegaram did the work people said women could not do. “I [even] learned things from the masons while on the job!” she said.

But her successes didn’t mean she went unscathed. She recalled how, on her very first day at the Kandy Peasantry Commision office, the Kandy Government Agent called her to come and take a look at his toilet.

It was the Chief District Engineer who stepped in, sending someone else to attend to the matter instead of her.

“It never happened [again]. That was the only time,” she said, adding as an afterthought, that it was maybe the Chief District Officer, who was a fatherly figure, who had prevented a recurrence.

Dr. Sivasegaram was later transferred to the Designs Office in Colombo, where she became the first female Chief Structural Engineer in 1978. During her time there, the Designs Office worked on numerous notable structures, like the Police Headquarters, the National Library and the National Archives in Colombo.

The engineering field in Sri Lanka changed quite drastically after President J. R. Jayawardene introduced the ‘open economy’, Dr. Sivasegaram said. “Suddenly things were going out to foreign companies. The Koreans—Keangnam—did Sethsiripaya. It was a British firm that did Isurupaya.”

Still, Dr. Sivasegaram persevered, but after the riots 1983, left the country for England, with her husband and son, only to return after their son graduated. On arrival, Dr. Sivasegaram joined the Open University in Nawala, to be close to her ageing parents, and was instrumental in revising many of the Engineering textbooks.

Engineering In Sri Lanka Today

Dr. Sivasegrama believes that things have not changed too much in the industry since her time. “But attitudes are different and not always in a good way,” she said, drawing attention to the lack of dedicated teachers nowadays.

“Earlier, when we were studying, the lecturers were lecturers 100% of the time. Now, people want to do consultancy which brings them money, and that has changed attitudes. There aren’t that kind of dedicated teachers anymore,” she said.

She also thinks the while universities in Sri Lanka are keeping up with all the advances in the rest of the world, the education system in Sri Lanka needs to change.

“People are going for tuition classes and getting through [exams] because of them. They memorise. They don’t study on their own anymore and that has affected the kind of people we get,” she said, adding that fluency in English was also necessary but sorely lacking. “It’s difficult for those who can’t catch up to the required standard of English. Students who cannot express themselves will get left behind.”

Dr. Sivasegaram said she was glad to see more women in the engineering faculty now, than before. “In fact, one of the best I had was a girl from Kurunegala. She was thinking on her own, and doing very good work.”

Unfortunately, the obstacles women faced in her time are still prevalent today. “Her father decided she should be married and stopped her. I was really disappointed,” Dr. Sivasegaram said.

Going by Dr. Sivasegaram’s recollections, it’s clear that Sri Lanka may be keeping up with the world in educating Engineers, but conservative values still hamper women from exploring their full potential.

Which is all the more reason to celebrate those like Dr. Sivasegaram, who have achieved heights in their profession, despite the obstacles set before them.