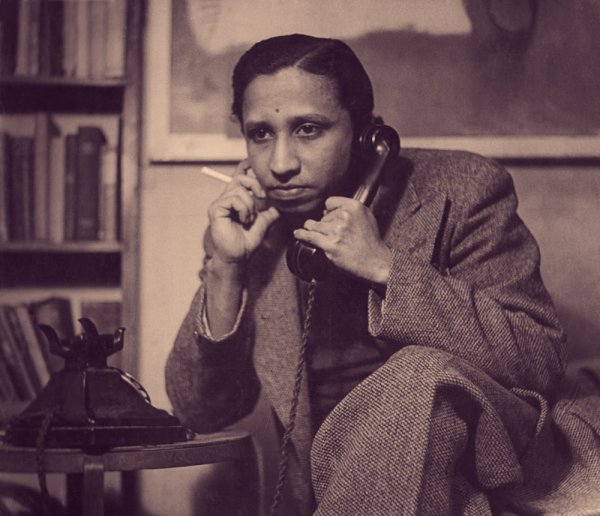

When former journalist and social worker Sharmila Seyyid (32) published her first book of poetry, Siragu Mulaitha Penn, in 2012, little did she know that it would decisively change her life.

Translating to The Women Who Grew Wings, the collection touched on women’s struggles — and included a piece about legalising sex work. In August 2012, former Justice Minister Rauff Hakeem was at the book launch. As luck would have it, he read out loud the poem about sex work. The following day, Seyyid received a call from the BBC Tamil for an interview, during which she was asked about her views concerning sex work. Her response was candid — if it was legalised and accepted as a career, it would provide protection to women who were exploited in the industry.

Coming from Eravur, a conservative village in the East, speaking in favour of legalising sex work was considered scandalous and haram. The Muslim community back home reacted explosively, attacking her not just with criticism and rage, but also by issuing death threats.

The campaign launched against Seyyid in 2012 included explicit images with her face photoshopped into it, and false claims of her having been raped and killed. At a certain point, even her family believed she had been murdered and was frantic with worry. Spurred on by extremist elements in the Eastern Province, the community branded her a whore and an outcast.

Over the course of her ten-year-long career, Seyyid had served as the District Women’s Coordinator at the Ministry of Cooperatives and Internal Trade; the Child Care and Women’s Affairs Coordinator at the Eastern Province Ministry of Health, Sports and Information Technology; and as the Community Coordinator at the Association of Women with Disabilities for the European Union, among other things.

Despite her impressive work history and reputation as a social worker in the north and east, the interview she gave the BBC made her infamous in her hometown. Intense social media campaigns were launched, where her photos were circulated among WhatsApp groups and Facebook pages, along with instructions to kill her on sight. Though Seyyid was living in Colombo at the time, her family back at home was ostracised by the local community.

“My sister and I were running a school in Eravur. Unidentified groups of men visited each student’s house, and threatened them. They told the students and their families not to step into the school. Even three-wheel drivers refused to go on hires with my family. They’d tell us they couldn’t because of the backlash they would face if they were associated with us,” she said.

In December 2012, Seyyid, a divorced mother with a two-year-old son, made her way to India. She lived there in self-imposed exile until tensions simmered down a bit. During this time, she completed her higher education, and managed to publish her first novel, Ummath, in 2014.

The Women Who Grew Wings

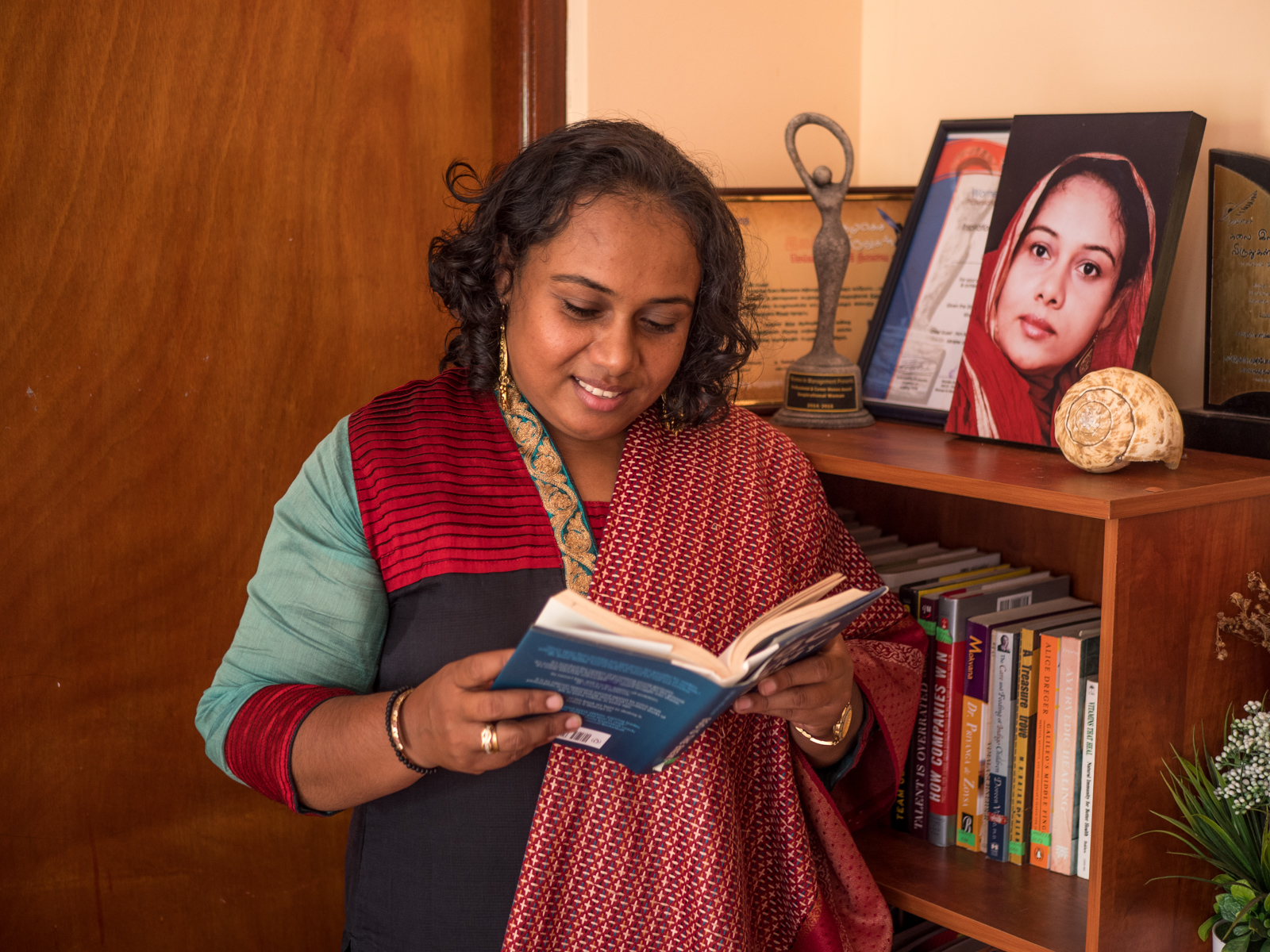

Now, sitting in her residence in Kotte on a hot Friday afternoon, Seyyid tells us that the response for Ummath was also mixed — many people, especially pro-LTTE Tamils and fundamental Muslims in the North and East, hated the book. She tells us that the book is based on the experiences of women she has worked with over the years. First published in Tamil, it won the Best Novel of the Year Award by the Tamil Nadu Progressive Writers’ and Artists’ Association in 2014, and was translated and published in English by HarperCollins earlier this year—a rare feat for a Sri Lankan writer.

“Many people rejected these stories [in Ummath] as lies. Others applauded them. I don’t mind when some people call them out as lies, because for me, they’re all true.”

One of the main characters in the novel was based on a former LTTE female soldier who lived with Seyyid for a few months after the war. The woman was emotionally distraught, and had not received necessary psychosocial support.

“I gave her a notebook and asked her to write. She said she isn’t a writer, so she can’t, but I encouraged her to maintain it like a diary,” said Seyyid. “I met many other women just like her, and learnt a lot of things that came as a shock to me as an outsider — that not all Tamils rooted for the LTTE, that many joined the movement because of poverty and so on. As a result, many people aren’t happy with the novel because it highlights discrimination faced by the women in the north-eastern communities. The Muslims weren’t happy with it, and the Tiger supporters weren’t happy with it because I wrote about how the LTTE brainwashed and manipulated people.”

On Living In India And Returning Home

Seyyid spent her first few months in India travelling and living in ashrams with her son Bhadri, before eventually pursuing her Bachelor’s in Social Work while living there.

“I didn’t really earn while I was there, and sustained myself on my savings,” she said. “I didn’t live in big hotels or anything of the sort. But by the time my son was three plus, I had to start thinking about his education and his future…so I decided to come back.” Given that no one had been able to pinpoint her location for three years, she figured that it would be safe to return if she continued keeping a low profile.

“No one except for my mother knew I was in India. I didn’t tell anybody, not even my father or my publishers. None of my family knew where I was or what I was up to, because my brothers-in-law dislike me.” Being associated with her was a danger in itself, and her extended family wanted nothing to do with her. Even now, Seyyid is estranged from her sisters.

“It was very hard, especially the first year. I had worked in the media, in the NGO sector, and felt abandoned, and that none of them supported me. I was targeted for three whole years and the mainstream media in Sri Lanka didn’t take a stance. I felt really sad and disappointed,” she said.

Making A Fresh Start

Now though, things are different.

With some of her past struggles behind her, Seyyid’s home now doubles as an office space for Mantra Life, a social enterprise that she founded upon her return to Sri Lanka in 2015.

Given her work and personal experience of the socio-economic vulnerability of women, Seyyid recognised the need for a ‘safe space for women.’ To this end, she established an organisation which aims to reduce the disparities between men and women in the economic, political, and social spheres.

The organisation now focuses on skill development training for women and girls, female education, and providing social and economic support for women.

“Mantra Life is a concept,” Seyyid tells us. Now in its third year, the organisation helps women become economically independent, has a cafe run by a single mothers’ group, and also provides art therapy, yoga, meditation, and inner dance and healing therapeutic training.

Mantra Life is more of a community than an organisation, and is an environment that she trusts enough to leave her children in when she travels overseas for work and conferences.

“They say my second [adopted] son is a Mantra boy,” she laughs. “It’s the women who I work with who also take care of them. We’re all like one family now.”

Despite everything she’s been through, Seyyid isn’t stopping yet. She plans to expand Mantra Life and establish centres in rural areas across the country. She has finished another novel, which she hopes to publish in January.

As we’re wrapping up the interview, Bhadri, now ten years old, walks in and seats himself. What is it like, we ask, to have a mother who has been on the run with you and who is a well-known author?

“It’s just one novel,” he says off-handedly, adding that he doesn’t get what all the fuss is about. “Not like there’s a hundred of them!”