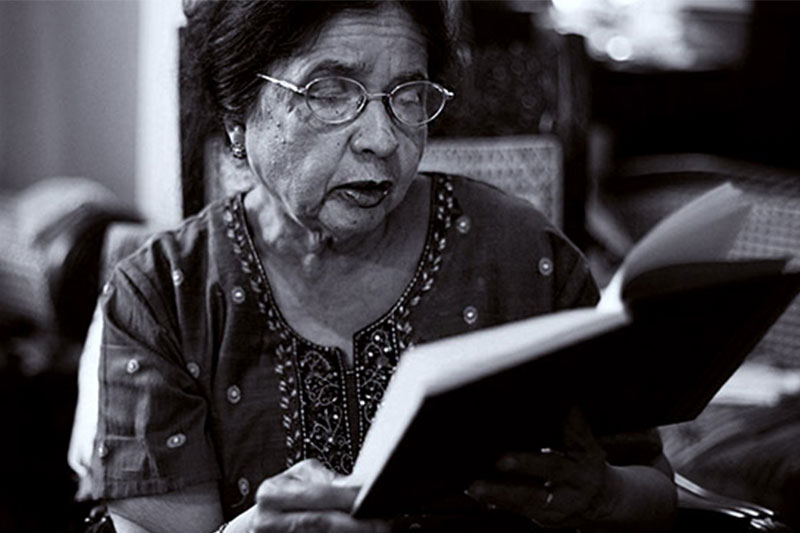

Last month, the literary world in Sri Lanka was set awash with grief when one of its titans, Jean Arasanayagam, passed away at the age of 87. A poetry and fiction writer, Arasanayagam was born Jean Solomons, in Kandy, on December 2, 1931.

Of her ancestry, Arasanayagam said, “…My father’s [side]—the ‘Solomons’—very academic, intellectual, moral, upstanding Methodists. On the other side, I had the ‘Grenier Jansz’—very genteel, but also intellectuals among them; artists, writers and poets and so on.”

Arasanayagam credited her family with influencing her greatly. “Everything was so ordered, so disciplined,” she said. “We are so turbulent in the expression of our emotions and feelings. But they had a marvellous sense of duty and responsibility—the womenfolk, especially.”

Arasanayagam had her early education at Girls’ High School, Kandy and her higher education at the University of Ceylon, Peradeniya, during the university’s ‘golden years’ in the 1950s, when Sir Ivor Jennings was at the helm.

“I remember talking to him when we were strolling about the campus,” she reminisced to writer Rajiva Wijesinghe, “with his walking stick, [asking us] how we were keeping..”

Having completed her education, Arasanayagam first joined the teaching staff at the Kurunegala Convent, and later, St. Anthony’s College, Katugastota—experiences she described as “rigid” and “alien” to her upbringing, although she “accepted it.”

Her own experiences growing up had been far more carefree, “ballroom dancing in the verandah…wonderful dinner parties…the homemade ginger beer, the love cake and the formal dinners,” she reminisced.

Arasanayagam was never happy with having her freedom curtailed, “We were all rebels in our family,” she said. “Absolute rebels. My mother couldn’t really cope with us because we did our own thing, all of us.”

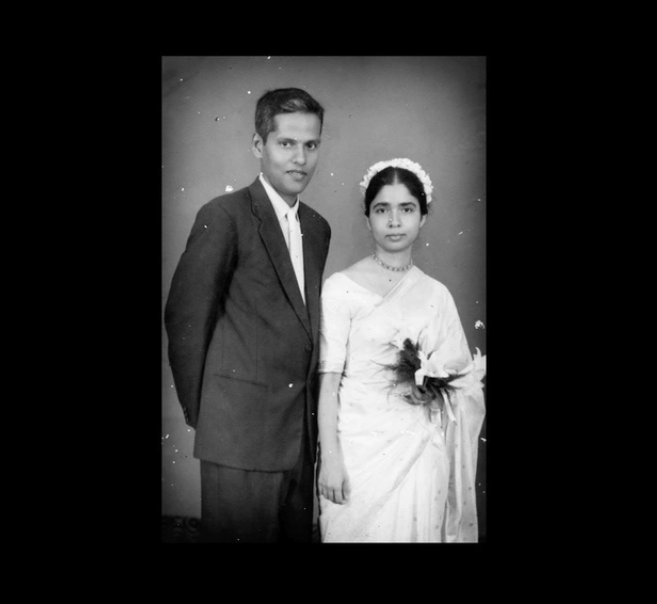

It was this innate rebelliousness that led her to defy the wishes of her own father, by marrying fellow writer Thyagaraja Arasanayagam—a Tamil from the country’s northern peninsula.

Arsanayagam’s experience of marriage was also very different from her upbringing. “We were given absolute freedom, to discover love, or relationships,” she said, of her time growing up. But she felt her mother-in-law, who was very “rigid in her views” would have a hard time understanding that.

This tension between her experiences of identity and culture informed her writing, providing her with the perspective from which to critique complex society through poetry and prose.

The accolades she accumulated were many. These included a Premchand Fellowship at the Sahitya Akademi in India, a doctorate in letters from Bowdoin College in the USA, the Gratiaen Award in 2017 and the highest state honour ‘Sahityaratna’, for lifetime contribution to literature in Sri Lanka.

Arasanayagam, in the true spirit of an artiste, did not place much emphasis on these successes. In an interview with Newsfirst, she said, “… For me, awards, do not mean any kind of celebrity status or material gain. Those do not count in my agenda. It’s the creativity that inspires, and what through the years I have learned of giving one’s self and carrying on this mission to change the world—That’s what the writer has to do, without fear.”

Arasanayagam wrote a vast trove of poems and collections of short stories, and is credited with influencing entire generations of writers on the island. Harshana Rambukwella, a family friend and one among the many she inspired told Roar Media, “…She had a formative influence on my choice to follow literature. She was instrumental in introducing me to a literary world and later on, her poetry became the focus of my scholarly studies.”

Although her work dealt with many complex topics, colonial legacy, womanhood and identity among others, her ‘Apocalypse ‘83’, on the ethnic riots of 1983, is considered a seminal body of literature.

Arasanayagam and her husband ‘Arasa’ were forced to hide from the marauding mobs that were burning the houses belonging to Tamils, and were eventually relocated to a refugee camp.

“I understood that my sense of safety was forever imperilled, forever destroyed. You are never yourself again,” she said of that experience. “Since then I find myself constantly peering into the interstices of the past, trying to unpick all the threads.”

The late Professor Ashley Halpe, wrote in the foreward to her book, “The poems convey the gathering of the storm, the immediate violence, both as she saw it and through various personae, the forced contemplation of what had happened in the period in the refugee camps, the thought of exile— “can I rent a country / as I rent out a room? The recognition “I didn’t know this country.” (Exile 1)”—words that continue to find relevance decades later.

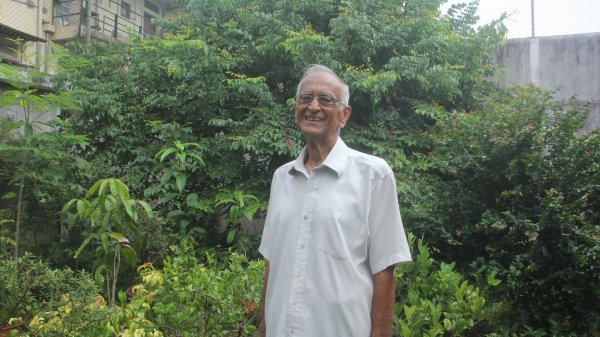

A medley of words recurring describe Arasanayagam: exuberant, charismatic, generous, opinionated. Her last neighbour, artist Yasmin Buckman recollected Arasanayagam as being a “colourful personality”.

“She [Arasanayagam] moved next door two or three years after my husband died in a vehicular accident,” Buckman told Roar Media. “My connection with Jean was instant. She was a warm-hearted person who loved my son dearly. She was very fond of us. She was caring of everyone she was close to. When I was faced with a problem, she was always there for me.”

“It was one of the many things brought up during her funeral,” she continued. “How she cared for people. There was a chair in her verandah, surrounded by a magnificent garden. Whenever she used to sit there, I could see her from the window. She would wave to me from her chair and I would go to her. We would spend hours enjoying each other’s company. I will dearly miss her.”

Arasanayagam was empathetic and described herself as a “poet who is human”, her only superpower being her rich imagination, captured succinctly in her short poem, ‘Poet’ —

She tells herself,

“I am common

Anonymous like all others

Here.

No one knows that I have magic

In my brain.”

Arasanayagam will be missed.