Ahnaf Jazeem and I are communicating through a translator. He speaks and writes in Tamil, and I do neither, but I’m listening hard to how he answers my questions. Slow and guarded when I ask about the time he spent in detainment, steady and rehearsed when rehashing the circumstances surrounding his arrest, quick and impassioned when I ask about poetry, politics or his perspective on the circumstances this country has found itself in.

“Military repression does not discriminate between the north, south or east,” Jazeem said. “The best example is the aragalaya – the government demolished the aragalaya by using military violence. Common people can be repressed by politicians anywhere.”

He’s right – after months of sustained protests against the Sri Lankan government forced a degree of social consciousness onto pockets of society that previously benefited from its absence, a desperate stab at maintaining control came via a pre-dawn military raid on the GotaGoGama protest site at Galle Face on 22 July. More than a month later, the arbitrary arrests and interrogation of individuals crucial to the aragalaya keep coming.

The most recent arrests are those of Inter University Students’ Federation (IUSF) convener Wasantha Mudalige, activist and student union member Hashantha Jeewantha Gunathilake, and Inter University Bhikku Federation convener Galwewa Siridhamma Thera. On 22 August, President Ranil Wickremesinghe, in his capacity as Defence Minister, granted approval for all three to be detained and interrogated for 90 days under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) — the same piece of highly-criticised legislation used to arrest and detain Jazeem for 19 months beginning in May 2020.

“If they want to arrest you tomorrow, they will do it under the [PTA],” Jazeem told me. “It applies to me as well as to you – to all writers, journalists and anyone who tells the truth, no matter what language they use.”

Taken In

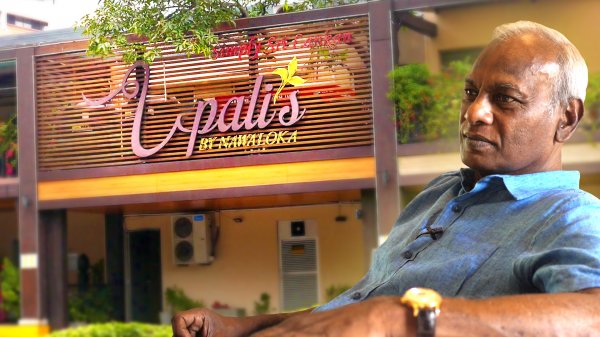

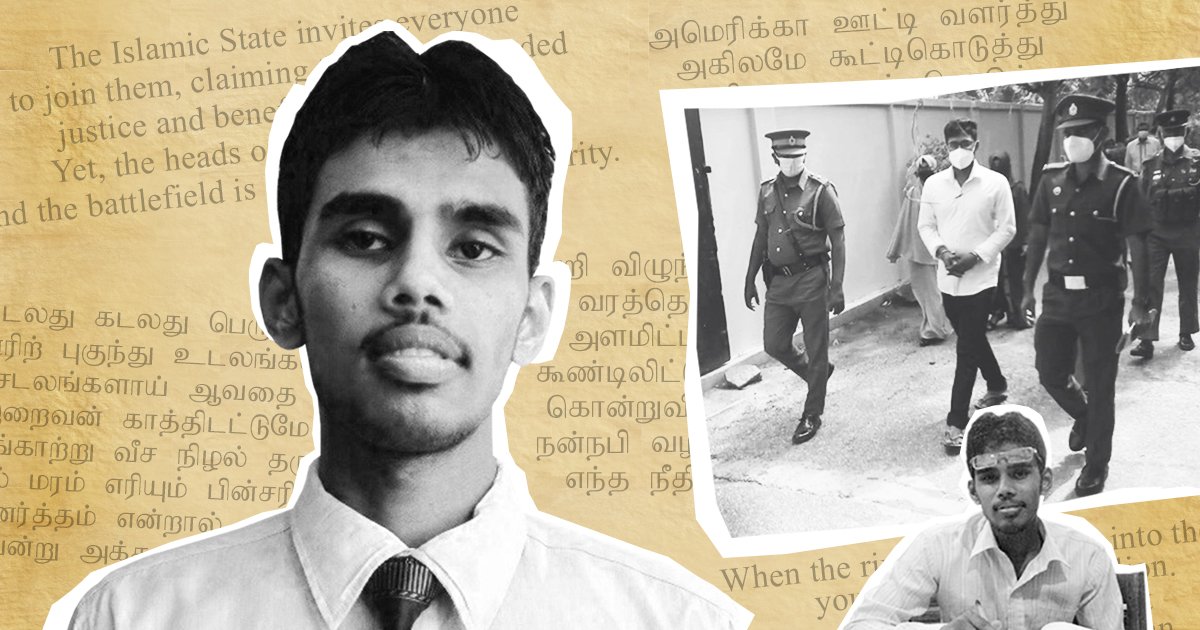

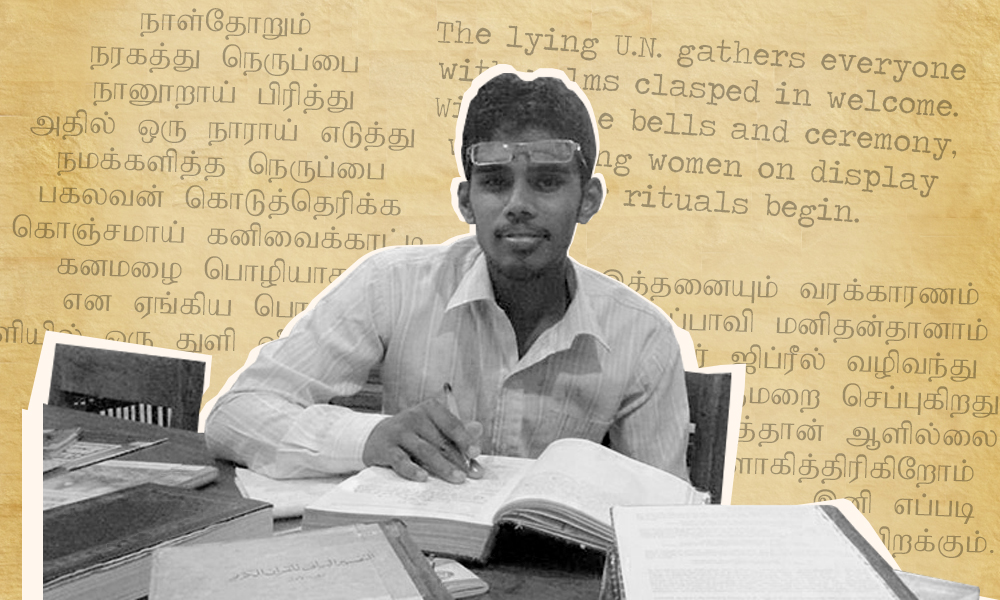

In 2017, Jazeem, a student at the time, published his debut collection of poetry, Navarasam. He went on to complete his studies and began teaching Tamil literature at a school in Puttalam. Almost three years later, on 16 May 2020, he was arrested at his home in Mannar by the Terrorism Investigation Division (TID) on allegations that his poems promoted religious extremism. They looked through his phone and laptop, raided his bookshelf, and confiscated roughly fifty books, as well as several hundred copies of Navarasam. They then told him to prepare for a three-day inquiry, with no direct mention of an arrest.

Taken away at 8:30pm that day, Jazeem did not return home until 19 months later.

“Those 19 months were a difficult period of time,” Jazeem said. “I was moved to several places – Tangalle, Colombo, the Navy jail. I wasn’t even kept in the same place inside [each prison] for long – second floor, then sixth floor, then a different cell.”

The circumstances of Jazeem’s detainment seemed engineered to break him. He said managed to get a copy of the Quran in prison, which he read daily. He was ill-treated by officers of the Terrorism Investigation Division (TID), often underfed or outright denied food and drink. In a letter to the Inspector General of Police (IGP) in May 2021, Jazeem’s lawyer, Sanjaya Wilson Jayasekera, stated, “My client’s family reasonably suspects that this ill-treatment is intended to further intimidate, mentally harass, weaken, and force my client to give self-incriminating statements to the TID.”

Also in May 2021, thirteen high-profile organisations — both local and international — issued a joint statement calling for Jazeem’s immediate release. These included Amnesty International, PEN International, Journalists for Democracy in Sri Lanka (JDS) and Human Rights Watch.

Then on 15 December 2021, Jazeem was granted bail. A photo taken shortly after showed the poet reunited with his parents and brother. Jazeem’s mother leans against him as he holds her with both hands. His brother and father look relieved, but weary.

“After the presidential election in 2019, a racist government came to power under the rule of Gotabaya Rajapaksa. After the Easter attacks, when they needed a coverup, innocent people were caught — and I’m one of them, though my case has nothing to do with the attacks,” Jazeem said.

“If they are causing this many problems over a poem, what will happen to those who try to reveal the big truths? How will they survive in this country?, “ he asked.

Poetry As Politics

Jazeem has always seen poetry as having a larger purpose. The day after the Easter Attacks on 21 April 2019, he published a poem condemning the attacks on his blog. He stayed home over the following weeks, as the aftermath of the bombings saw anti-Muslim violence break out across the island. But after his arrest, the TID told Jazeem that Zahran Hashim, the alleged mastermind behind the bombings, was partly inspired to carry out the attacks after reading Jazeem’s poetry.

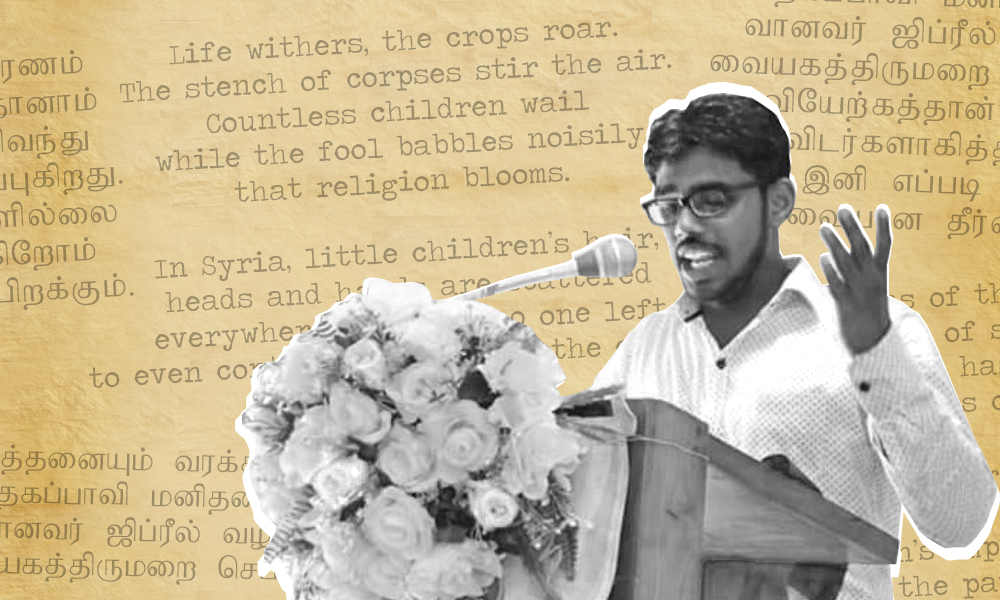

“If [Navarasam] was the real issue, the National Library [of Sri Lanka] wouldn’t have approved it, or the government would have banned it,” Jazeem said. “Navarasam has nothing to do with promoting extremism; the poems condemn poverty, discrimination, and calls for world peace, not war.”

His poems have been translated into English and Sinhala on a site called Free Ahnaf Jazeem. The collection has a determined, persistent political voice, and a moral thread running throughout that is clearly derived from Islamic principles – submission to God’s will, the eventual uncovering of truth, and the inevitability of divine justice.

Jazeem is hyper-aware of politics. “Poems cannot be separated from politics, all art is mixed with politics,” he said. “Even when you write a love poem, it has to do with family structure, the legitimacy [of the relationship], and the government’s rules. Whatever you write, there will be a political aspect to it.”

With his poems, which emulate the style and structure of classical Tamil poetry, Jazeem doesn’t mince his words. He rails against America for their hypocrisy and continued destruction and exploitation of the Middle East — accusing the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) of the same. Complicity with and apathy to violence and suffering are treated with as much contempt as the crimes themselves, and the silence of the international community and the United Nations (UN) are not spared critique. Reading his expressions of solidarity with the people of Palestine, Syria, Afghanistan, Kashmir and Burma, it is eerie how the circumstances of Jazeem’s life have come to mimic the blatant injustice and manipulation of truth that his art denounced.

Kavichakravarthi Kamban, Avvaiyar, Thiruvalluvar, Subramania Barathiyar and Bharathidasan, he cites as key poetic influences: “Their poems spoke about social reforms, political awareness and independence, which influenced me to write about democracy, commonality and peace,” he said. “A poem helps create awareness within society about the problems people are facing. The ruling elite don’t like when people are aware.”

“Literature is the best art, and poetry is the best literature,” he continued. “That’s why I chose it. Not everybody can write poetry.”

Designated Person

Jazeem, at only 27 years-old, has already experienced the worst of the Sri Lankan state, its adversaries, and its advocates. His parents were expelled from their native Mannar by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) during the civil war, and Jazeem was born in Puttalam. “As I grew up, I listened to people speak of us like refugees, and I began to wonder why this was happening,” he said. “In the name of protecting the Tamil community, the LTTE persecuted other communities. This precedent of using racial identity for political gains is getting very popular in our country.”

“In 2014, the [anti-Muslim] riots happened at my doorstep,” Jazeem said. He was studying at the Naleemiah Institute of Islamic Studies in Beruwala at the time, and much of the violence took place in the area and neighbouring Aluthgama and Dharga Town. “[The riots] opened my eyes. Sri Lanka is a country whose leaders think only of themselves and work only for themselves. They instigate racism and extremism and terrorism for their own gain,” he said.

On 1 August, the government’s list of ‘Designated Persons’ was updated by the Ministry of Defence, and Jazeem’s name was added to it. It accuses him of “terrorism-related activities,” despite the fact that the case against him is yet to be even taken to trial. The trial is now scheduled for 10 October, but adding his name to the list means that he cannot obtain a passport, access any government services, or find employment until his name is cleared.

“I feel like I’m not a citizen of this country,” Jazeem said. “I’m afraid for my future – I don’t know what will happen to me. Will I need to hide for the rest of my life?”

He fears that this will set precedent to silencing writers in the country. “Just as the people’s uprising was eliminated and the struggle crushed,” he said. “There is no freedom of expression for the oppressed as far as the ruling class is concerned.”