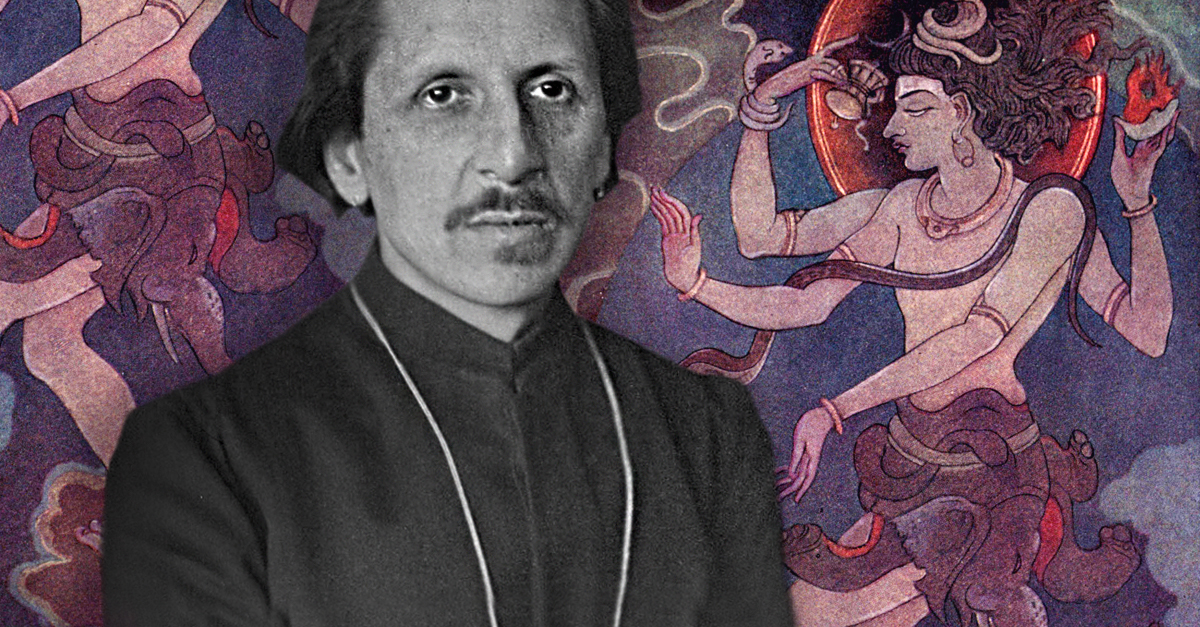

In November 1918, Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy, a Sri Lankan art historian and philosopher, published The Dance of Shiva, a collection of 14 essays on varied subjects, united in its uniquely South Asian perspective. “Hundred years on, his wisdom still resonates with people, in Sri Lanka and abroad,” said anthropologist Hasini Haputhanthri, who moderated a recent event on Coomaraswamy’s life and work at the International Centre for Ethnic Studies.

Organised by the American Institute for Lankan Studies, the public lecture reflected on the relevance of Coomaraswamy’s work in the present day. A prolific writer, Coomaraswamy studied and contributed to a variety of subjects: geology, visual arts, aesthetics, literature, folklore, mythology, religion, and metaphysics. Even The Dance of Shiva covers a range of seemingly unrelated topics, which are tied together by “an Indianness in approach”, whereby used the teachings of ancient Indian philosophy to illuminate issues of his own time.

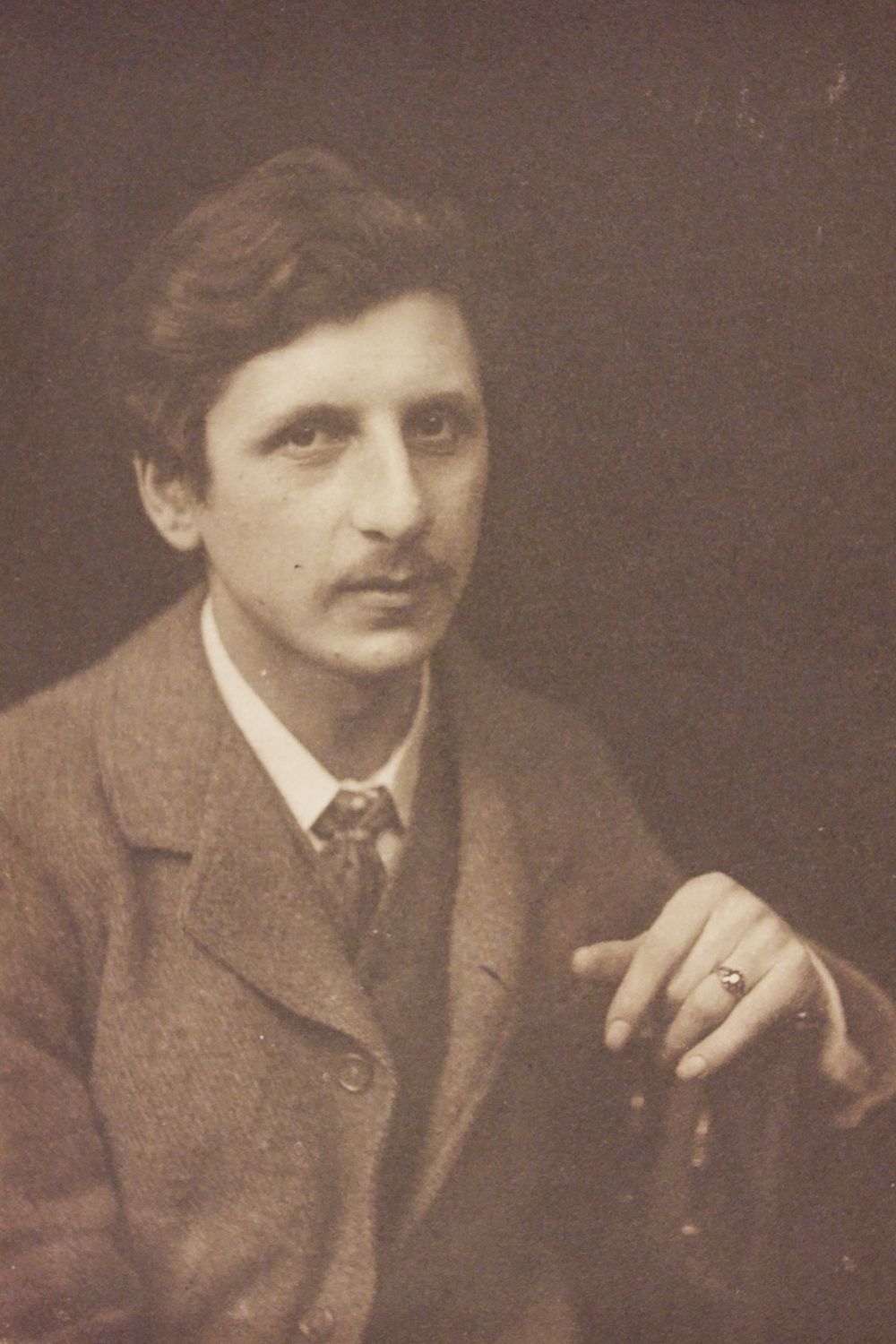

Photo credit: worldwisdom.com

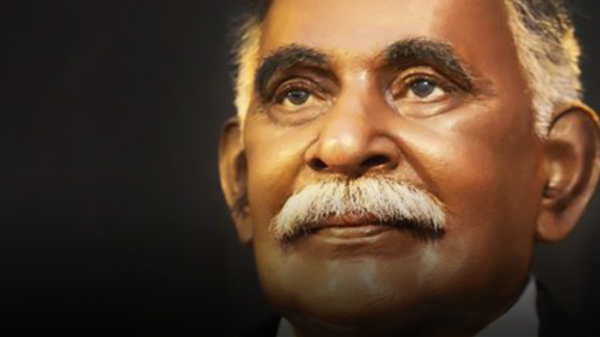

Born in Sri Lanka in 1877 to a prominent legislator, Muthu Coomaraswamy, and his English wife Elizabeth Beeby, Coomaraswamy was brought up in England following the early death of his father. He studied botany and geology at Wycliffe College and London University, and returned to Sri Lanka in 1903 with his wife Ethel, to pursue a career in those fields.

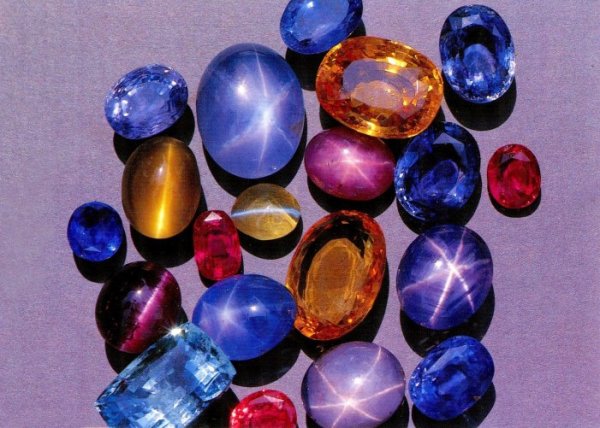

“Ananda Coomaraswamy’s numerous writings about geology mostly relate to the work he did while employed as the first Director of the Mineralogical Survey of Ceylon,” said Janice Leoshko, professor of art history at the University of Texas, and the main speaker at the ICES lecture. During his tenure, he discovered and identified the radioactive mineral thorianite, which instigated a correspondence between him and Marie Curie. However, in his travels around the country, he saw the effects of British colonialism on the local cultures of Sri Lanka, most significantly on the artistic traditions of the country.

“He declined re-appointment as Director of the Mineralogical Survey, in part disillusioned by various actions of the colonial government and in part due to his growing interest in cultural issues,” Leoshko said.

Coomaraswamy, in articles for local newspapers, as well as the Royal Asiatic Society, “repeatedly expressed his concern about the colonial government controlling and changing all aspects of Sinhalese society,” Leoshko said, citing essays like ‘Kandyan Art, What It Meant and How It Ended,’ and ‘Open Letter to the Kandyan Chiefs,’ that called for the preservation of Sri Lanka’s architectural heritage. Eventually, these efforts culminated in his first major book, Medieval Sinhalese Art, published in 1908. “It is still studied today, and for good reason, as it is one of the most significant works of Sri Lankan scholarship,” said Jagath Weerasinghe, professor at the Postgraduate Institute of Archeology, University Of Kelaniya. “The book is many things, but mainly it is a study on the arts and crafts of Kandyan peasants in the colonial era, with an account of the structure of society and the status of craftsmen at the time,” he said.

Rather than examine the art of Sri Lanka nobles, which Coomaraswamy saw as an extension of Indian aesthetics, he looked at the art of the common people, made not only for its aesthetic value but for general utility — or “the satisfaction of present needs”, as he called it.

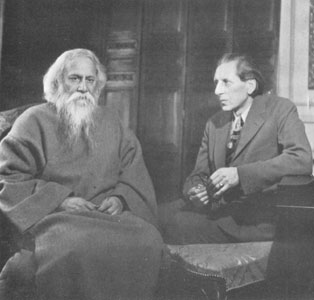

Photo credit: www.worldwisdom.com

His interest in traditional crafts was governed by the conviction that something vitally important was disappearing because of modernism. In Sri Lanka, as well as in England, he lamented the growth of industrialisation, because of its destruction of local arts and crafts. “He was particularly influenced by the artist and social reformer, William Morris, who felt that the poor quality of manufactured goods was eroding popular taste and reducing the lives of craftsmen to production-line workers,” Leoshko said. As automation and mechanised machinery made production faster and more efficient, the influence of the craftsman was no longer seen in their creations. He believed the new values and patterns of urbanisation and industrialisation were disfiguring the human spirit and he protested vehemently against the conditions in which many were forced to carry out their daily work and living. “A primary reason for writing Medieval Sinhalese Art was to document the artistic achievements of a people whose way of life could be lost permanently,” said Weerasinghe.

Coomaraswamy lived and worked during the late era of European colonial empires, when Western thought dominated intellectual circles. Although there was a growing interest in the philosophies of the East, especially in Indian philosophy by writers like Henry David Thoreau and Arthur Schopenhauer, these were often just Indian ideas that were inserted into Western philosophical discourse. According to Leoshko, “Coomaraswamy was a pioneer historian of art and interpreter of Indian culture to the West.”

His approach was fresh and different to the writings on Asia by Western thinkers, as “he set about dismantling Western prejudices about Asian art through an affirmation of the beauty, integrity and spiritual density of traditional art in Ceylon and India,” she added.

Photo credit: sutrajournal.com

Coomaraswamy migrated to America in 1920, following his divorce from his first wife Ethel. He later married the American artist Stella Bloch, who was 29 years his junior. As the curator of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, he along with his wife became involved with the bohemian art circles in America. Coomaraswamy described his work in The Aims of Indian Art, as “research not only in the field of Indian art but at the same time in the wider field of the whole of traditional theory of art and of the relation of man to his work, and in the fields of comparative religion and metaphysics…” During the late 1920s, Coomaraswamy’s life and work somewhat altered trajectory. The collapse of his third marriage, ill-health and a growing awareness of his impending demise deepened Coomaraswamy’s interest in spiritual and metaphysical questions.

In The Dance of Shiva, Coomaraswamy argues that modern Western philosophy created a distinction between “the sacred and the profane”, that was not present in Indian or even Greco-Roman culture. In these traditions, he believed, the heavenly or spiritual world was interconnected with the real, everyday world, and that the use of the two different terms itself obscures the single unified world presented in ancient texts. Religious artefacts, such as the necklaces and anklets of the god Shiva, were the medium of spiritual-material interaction, and in the use of these artefacts, Shiva is invoked to destroy, or rather transform, the current world.

Photo credit: metmuseum.com

Through his studies of South Asia, Coomaraswamy contributed heavily to the Traditionalist school of philosophy, alongside thinkers like René Guénon and Frithjof Schuon. The central idea of this school was Perennial Philosophy — that the world’s religious traditions all point to the same universal truth, and that the scholars of the West were lacking this perspective.

Although born in the Hindu tradition, he had a deep knowledge of the Western philosophies as well as a great expertise in—and love for—Greek metaphysics, especially that of Plotinus, the founder of Neoplatonism. As such, his metaphysical writings aimed at demonstrating the unity of the Vedanta and Platonism.

Photo credit: worldwisdom.com

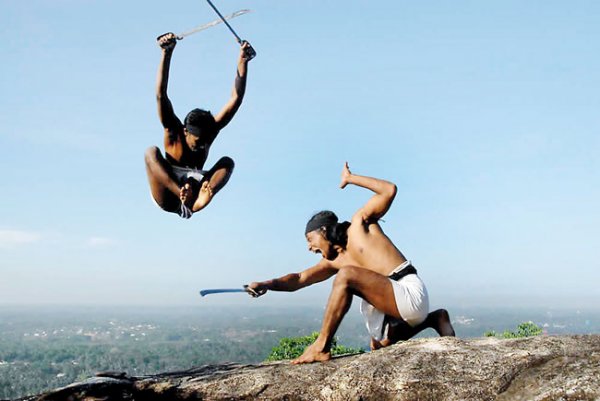

Despite his many notable contributions to the study of art and culture, Coomaraswamy sometimes had a blind admiration for Indian society. He is quoted as saying that “the Brahmanical caste system is the nearest approach to a society where all interests are considered identical and is the only true communism.” Following the social system prescribed by Vedic philosophy, he advocated for arranged marriages and even justified the practice of sati, in which widows would throw themselves onto their husband’s funeral pyre. However, Weerasinghe stressed that it was important to place Coomaraswamy in the socio-cultural context of the early 20th century, when Asian culture was oppressed by colonisers. “He looked to our own history to guide our future, and this perspective is still applicable today,” he said.

In 1906, Coomaraswamy founded the Ceylon Social Reform Society of which he was the inaugural president and driving force. The Society dedicated itself to the preservation and revival not only of traditional arts and crafts but also of the social values and customs which had helped to shape them. In the words of its manifesto, it discouraged “the thoughtless imitation of unsuitable European habits and custom.” Coomaraswamy called for a re-awakened pride in Sri Lanka’s past and in the country’s cultural heritage, and a reflection on how the nation could be reshaped by those values it upholds, rather than those it imitated.