In the aftermath of the Easter Sunday terror attacks, President Maithripala Sirisena ordered a social media ban lasting nine days, from April 21-30. The reasoning behind the ban was to stem the flow of fake news and hate speech that could incite violence. The first social media ban to be imposed in the country for these reasons was in response to the anti-Muslim violence in the Central Province in 2018, and it was this that was reintroduced following communal violence in Negombo and in the North Western Province in May this year.

But how effective are these bans in reality? They can only be implemented as a temporary measure since social media has become increasingly essential for personal and business interactions. Besides, even during the ban, most social media sites could be easily accessed using a virtual private network (VPN). This fact was illustrated in a study conducted by Sanjana Hattotuwa, Senior Researcher at the Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA), during the social media ban that followed the Easter Sunday bombings. The study found hardly any reduction in content produced, or in engagement on these platforms while the ban was in force.

Containing hate speech involves a fine balancing act, as harsh regulations can easily stifle freedom of expression guaranteed by Article 14 in the Sri Lankan Constitution. As full censorship is a threat to this freedom, we need a more informed and nuanced approach to identifying and limiting hate speech, while still allowing room for criticism, debate and dissent.

What Is Hate Speech?

The importance of free speech is founded on the belief that a ‘marketplace of ideas’—that is, a space

where any and all ideas and opinions are allowed to flourish and compete with one another—is essential to a healthy democracy. In this understanding, freedom of expression can only facilitate debate and dissent if it protects the right to voice controversial opinions and ideas.

So when does free speech cross the line into hate speech? Different countries and organisations have differing definitions, but according to Article 20 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which Sri Lanka is a signatory, speech that motivates discrimination, hostility or violence for a person or group based on their ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, disability etc., is considered hate speech. However, this definition obscures the variety of utterances that can very subtly breed hatred.

“The idea of using speech, or saying an utterance, never occurs in a vacuum. It is always interacting with others, it is always in a context,” said Achinthya Bandara, a linguist at the University of Colombo. “Both the speaker and the listener have an understanding of the utterance based on their culture, and it is based on this understanding that we categorise something as hate speech or not.”

In the case of Sri Lanka, research has mainly focused on hate speech against Muslims. However, there are also many examples of hate towards women, the LGBT community, Christians and even Buddhist priests who support religious harmony.

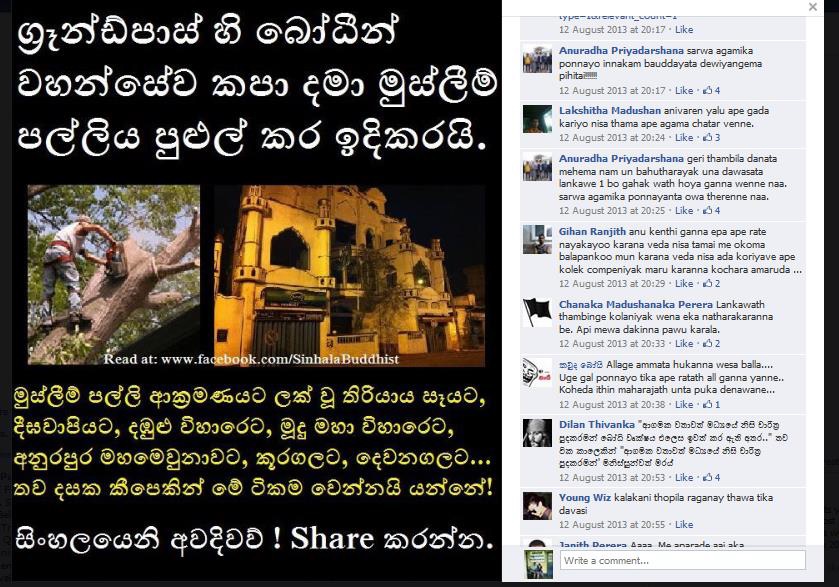

In a study on how hate speech is used in Sri Lanka, the CPA noted several unique characteristics. One of these was that the posts drew on a fear present amongst some members of the majority community, that their unique culture is threatened by a minority conspiracy to make their faith dominant in Sri Lanka. “I noticed in my research that the types of posts that motivate people to action, and the emotional frame they took…often involved a perceived threat, a denial of the mainstream narrative and then a mobilisation to action,” said Bandara. For instance, the sterilisation pill scare which led to the Digana riots, or the ongoing boycott of Muslim businesses by groups of Sinhala nationalists.

Often, hate speech is not obviously incendiary. Instead, it carries subtle cultural cues that can evoke strong emotions. “I looked into various words and phrases used in inflammatory posts, and identified ‘indexicals’, which are words where the full meaning only comes from cultural context,” said Bandara. “Words like Sinha-Le, Elam, Demalaa, Hambaya, or Thambi carry with them value judgements, either positive or negative, of the group referred to.”

Using these words don’t automatically qualify an utterance as hate speech, but they often indicate the speaker’s generalised feelings towards that group. “Fathima is used to refer to the general Muslim woman, and Mohammed for any Muslim man, along with assumptions about what kind of people they are,” Bandara said. “Even the word suddha, used to refer to any foreigner, falls under the same category, making the group seem different and strange, making them the ‘other.’”

Monitoring Hate Speech

Bandara is working on developing a machine learning programme, ‘Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count’ (LIWC), which can be used in such situations to identify the emotional content of a text. “I took pro-Sinhala and anti-Sinhala nationalist phrases (translated into English as the programme is still limited to that language) and took an analysis. This gave the programme an idea of what keywords and phrases are used in hate speech, so that [it] has the capacity to identify them in other contexts,” he said. However, there were many unforeseen obstacles to improving the accuracy of the programme.

One of the problems in identifying and controlling hate speech online, is that it happens in vernacular languages such as Sinhala and Tamil. The machine learning programmes for hate speech analysis are fed mainly in English, or languages using the Latin script. To add to this, communication on social media is often not in the standard form of the language, but uses dialects and colloquialisms, that a programme would have to learn on top of the standard variety. “The machine doesn’t have the capacity to think, rather it works by looking for patterns. Even the most sophisticated programmes have a lack of data which helps with identification: in other words, they have not been fed with enough examples for them to notice patterns accurately,” Bandara said. “Right now, using human moderators is more effective, but not as effective as a well-trained programme could potentially be.”

Regardless, even Facebook’s human moderation has been criticised for not giving its Sri Lankan consumers enough attention. With 6 million local users, Facebook, as well as its subsidiaries Instagram and Whatsapp, are a significant source of news and information in this country. But the company has been noticeably amiss when dealing with rampant hate speech on their platforms, citing the lack of Sinhala-speaking moderators. Inflammatory posts either manage to circumvent the community guidelines or Facebook only takes action months after they are published, long after the damage is already done.

Even when hate speech is recognised and flagged, prosecuting cases poses an additional challenge. In a study by the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), which compared hate speech legislation in six EU nations, it was found that successful cases were rare. They noted that there was no standard set of laws covering the topic, with each nation taking their own approach—some similar to cyber-bullying laws, others closer to slander and defamation suits. In Sri Lanka, these laws are similarly nebulous and difficult to enforce. For instance, perpetrators can be prosecuted under either the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Act, or under the religious freedom provisions in the Penal Code, or under the Prevention of Terrorism Act. Additionally, there remains a lack of legislation which deals specifically with the propagation of hate speech online.

Ultimately, however, just as blanket social media bans fail to address the root issues, even hate speech monitoring falls short in this regard. Although it can be very useful in preventing mobilisation and in ensuring stability, even the most advanced system will not dissuade people from the beliefs that they hold and share. Aside from measures to criminalise incitement of hatred, the UNHRC recommended “the promotion of inclusion, diversity, and pluralism as the best antidote to ‘hate speech,’ along with policies and laws to tackle the root causes of discrimination.”