On a hike through the wilderness near Kalthota in the Monaragala district, Ashan Geeganage, an archaeology enthusiast, stumbled across an ancient ruin hidden in the jungle, where he discovered four men performing a ritual. “They were preparing to dig up the place,” he told Roar Media, “and were making an offering to protect themselves from any vengeful spirits.” “When they saw us, they ran into the forest,” he continued. “We were very confused so we also ran away.”

Geeganage is a member of Lakdasun, a online community of travel, nature, and history enthusiasts, who have noticed an increasing amount of vandalism and looting, especially at unknown sites of archaeological interest in remote areas. “I worked in Monaragala for three years, and I would go on hikes in the country, often to see archaeological ruins,” he said. “Many sites I’d been to had already been vandalised by treasure hunters.”

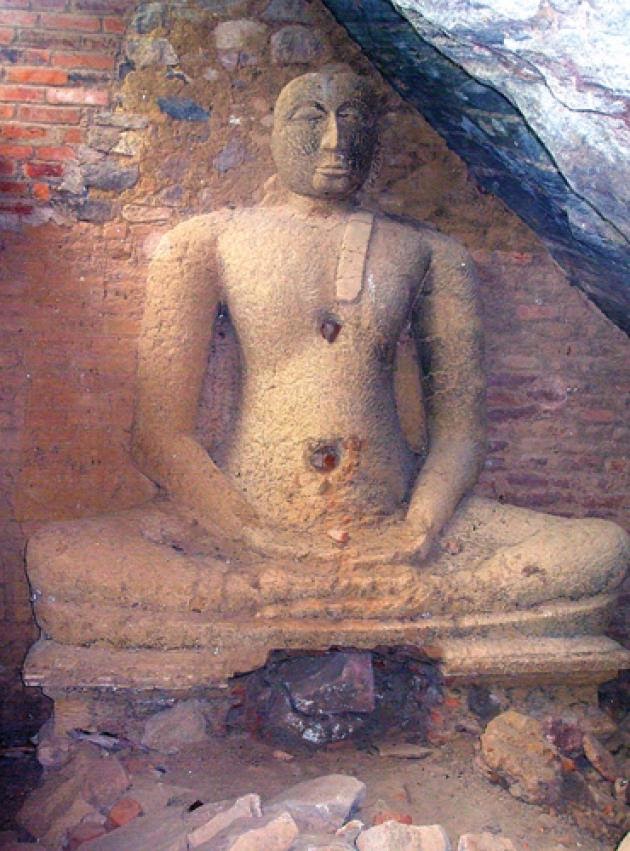

In August 2014, Geeganage and five other members of Lakdasun, journeyed into the heart of the Kumbukkan Forest Reserve in the Ampara district, in search of the Budupatuna Mahayana shrine complex. The site was discovered in 1985 by a team of Japanese archaeologists, with a statue of the Gautama Buddha and two of his followers, Avalokitesvara and Maithree Bodhisattva. When rediscovered by the Lakdasun expedition, two of the statues had been decapitated, either to obtain supposed valuables inside, or to sell as antiques.

Over the past decade, archaeological crimes have become more common, and are increasingly carried out by organised gangs. As Udeni Wickramasinghe, former head of the Special Unit for Prevention of Destruction and Theft of Antiquities was quoted as saying in this piece, “Earlier, you were more likely to stumble upon a harmless villager digging up earth with his farm tools. Today, heavy machinery is used, and the wrongdoers are not afraid of being seen.”

As evidence of this growing trend, during a raid in July 2017, the Mundalama police seized a water pump, an excavator, a lorry, a van, and a scanner worth Rs. 6.5 million. The suspects also offered the police a bribe of Rs. 600,000 to “look the other way.” In cases such as this, the machinery is usually brought to the site with the pretext that it will be used for construction, sometimes with official permits.

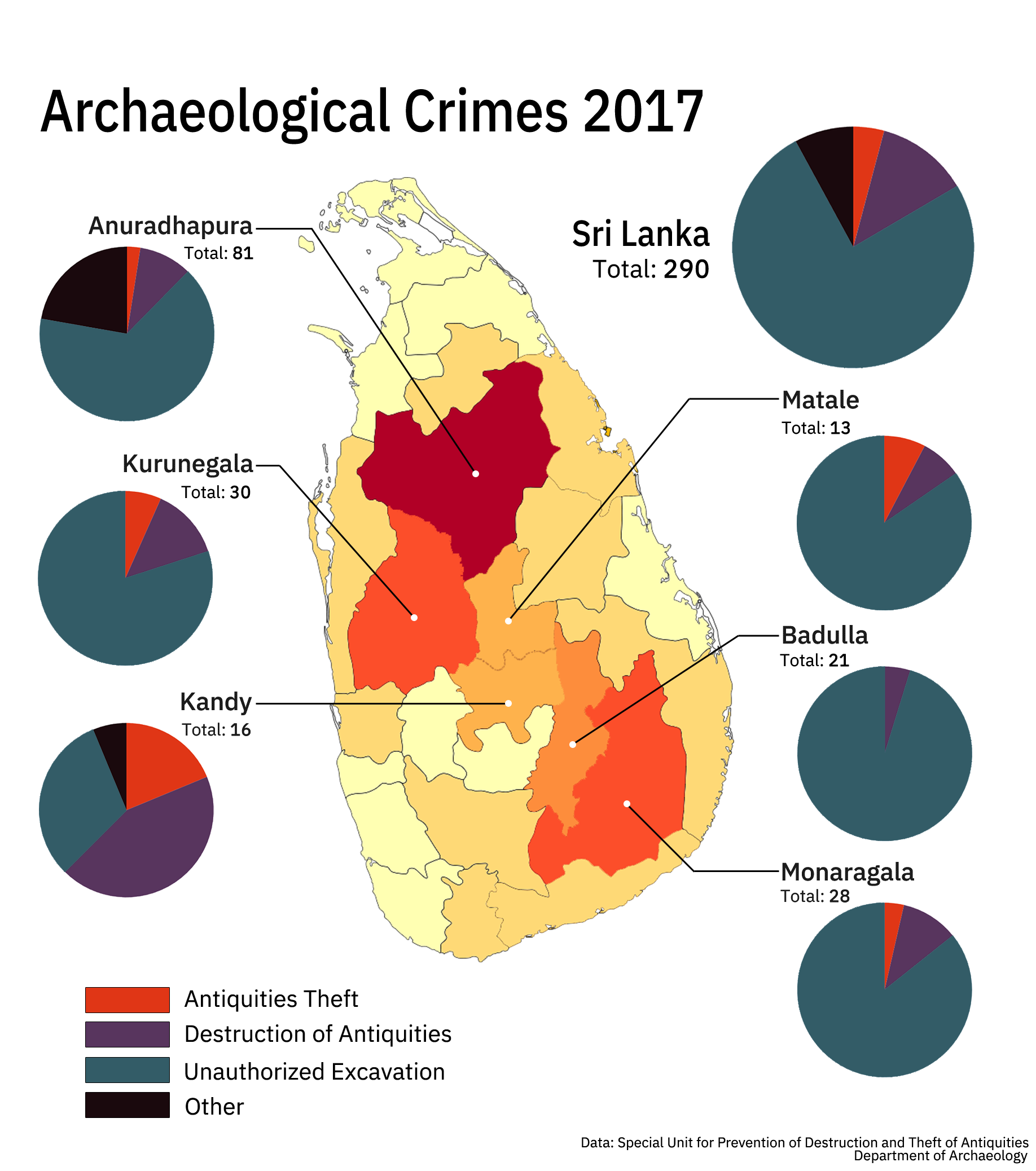

Under the Antiquities Ordinance, the Archaeological Department is given the responsibility of finding and cataloguing historical sites. It is authorized to undertake or subcontract excavations, and is charged with the protection of antiquities from theft or destruction. At the peak of the vandalism in 2012, 370 offences breaching the ordinance were reported to the Department. Although this number has since diminished, the number of offences reported remains high according to official statistics provided by the Department, with 230 in 2016, and 290 in 2017.

Facts vs Myths

Treasure hunters specifically look for gold, silver, and ivory items, which are assumed to be hidden in ancient ruins and temples. Items not of material value are discarded or destroyed, regardless of their historical or spiritual value. Wickramasinghe noted that “the problem is many people cannot distinguish between fact-based history and mythical epics.”

Folk tales are told about treasures hidden in ancient sites, and people often believe that local ruins contain undiscovered riches. “Even moonstones, which people in the past used to wipe their feet on outside their houses, have been broken to uncover precious items,” Geeganage said.

While the search for treasure is often futile, the lucrative market for antiquities further encourages people to loot ancient sites. In 2013, a Sri Lankan moonstone discovered in the house of a colonial British planter was sold for £553,250, or nearly Rs. 110 million. Six weeks after this news was published, a group of men dismantled and stole an entire moonstone from the Herath-Halmillewa Raja Maha Vihara in Kebithigollewa, after tricking the priest and tying up his guards.

Poor Enforcement

A part of the problem is the poor enforcement of the sale of illegal artifacts. When excavated legally, artefacts are catalogued and then can be kept for research, or sold to museums, international organisations, or antique shops. In order to transport, sell, or keep antiquities, there must be proof of the item’s legitimate acquisition, i.e. a paper trail leading back to an authorised excavation. However, the legal division of the Archaeological Department does not regularly confirm the origin of antiques sold in shops, and many shops operate without the appropriate licence from the department.

In order to curb these offences, the department has cooperated with the police and approved harsher punishments for treasure hunters; increased the fineable amount up to Rs 2 million, and implemented a mandatory prison term for the destruction of sites or artefacts. Additionally, the Special Unit for Prevention of Destruction and Theft of Antiquities has started a programme around the country raising awareness about preserving our cultural heritage.

Interestingly, folktales have been used to act as deterrents, instead of serving as encouragement to commit crimes. Villagers tell stories of people getting into accidents after incidents of looting, and as Geeganage observed, looters often make offerings before they dig up a site. Despite these measures, “they believe there is treasure, so they keep on destroying monuments,” said Dr Siran Deraniyagala, former Director-General of Archaeology.

A Lack Of Cooperation

In addition to the obstacles in their education campaign, the Archaeological Department also faces logistical issues. With around 250,000 archaeological sites in Sri Lanka, the department claims that they lack the funds and the staff to protect all those areas. Geeganage noted that many sites he had visited were not gazetted by the survey department.

According to Dr Raja de Silva, the Archaeological Commissioner (Director-General) from 1964-79, the increased activity of treasure hunting gangs is at least partly because of the lack of cooperation between the Archaeological Department and the Central Cultural Fund (CCF).

Dr De Silva himself was instrumental in creating the CCF in the 1970s with the help of UNESCO. Its purpose was to raise money, mainly from tourism in the Cultural Triangle, and financially support the Archaeological Department, which, as a relatively low-level government department, is not allocated significant funds. However, instead of fulfilling its supporting role, the CCF today carries out excavations in its own right.

“It was only meant to be a fund-raising body,” De Silva explained, “but now they give out permits for excavations and building projects, and charge discriminatory fees for entrance to historical sites.”

Although the CCF could step in to take on the role of protecting archaeological sites, its involvement is restricted to those sites which are popular with tourists, like Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa, Dambulla, and Sigiriya. With the funds it collects, the CCF plans projects to boost tourism in the Cultural Triangle, such as adding an electrical lift to Sigiriya. The thousands of lesser known sites are left to the Archaeological Department, which does not have the funds or staff to protect them. For instance, a site near Mullaitivu was recently given over to a group of Buddhist monks by the department, because of a lack of funds to carry out research themselves.

While there is certainly more both departments could do, there is no easy solution to this problem. Even though better protection of sites, and greater enforcement in the antiquities trade are critical, a more lasting solution would be to educate the public about the historical value of their cultural heritage, a mission that is complicated by the lucrative nature of the trade. “The answer is to educate the public not to destroy national heritage,” said Dr Deraniyagala, the former Director-General of Archaeology. “But they will say their stomachs are more important than national heritage. What do you say to that?”

Cover Image Credit: Ashan Geeganage