The Dematagoda Canal passes under Baseline Road at the Orugodawatta Junction and stretches a further 3 kilometres south-east. A young man, in a pair of jeans and a grey cotton v-neck t-shirt, is punting downstream, a few dozen feet east of the overhead bridge. He stops, takes a three-feet long weir skimmer and fishes out a stinking, sludge-covered, plastic school bag. His next attempt unearths a toilet brush. Out come plastic bottles, beer cans, slippers, and a host of other objects.

This scene plays out across multiple locations in and around Colombo. Every day, the city’s canal cleaners fish out an estimated 20 tons of trash—plastics, water hyacinth, and sludge—from Colombo’s 100-kilometre network of major and minor man-made waterways.

This amounts to 5,000 tons of waste per annum. Sadly, at least twice as much is not collected. Debris accumulation is not the only problem endangering the waterways: in certain parts of Colombo, sewage filters through the stormwater drains while in others, companies, big and small, flush out their waste oil and lubricants that form a thick layer over the water causing the death of fish, and severe—often irreversible—damage to the biochemical balance of aquatic environments.

The Sri Lanka Land Reclamation and Drainage Corporation (SLLRDC), the public authority charged with maintaining the waterways, faces an impossible task. Officers complain about a labour shortage: many cleaners are employed on a casual basis and turn up for work—in the words of an SLLRDC labour supervisor—only when they feel like it. The workers are ill-equipped; they toil in the scorching heat, alternating between precarious punting and heavy lifting. They come back the following day to repeat the thankless task. Or they don’t.

Colombo’s open waterway system—encompassing canals, lakes, rivers, and estuaries—however, has seen better times. During the Dutch colonial period, in particular, these inland waterways formed the spine of the country’s economic activity.

A Brief History

Historians credit King Veera Parakramabahu VIII of the Kotte Kingdom as having linked the Negombo seaport with Kelani River, by way of the first iteration of what is now the Hamilton Canal. At the time, the canal ferried cinnamon and other spices from the villages in Kelani Valley to the primary tradeport.

In 1521, a few years after first setting foot on what was then known as Kolontota, the Portuguese dug the Beira Lake in Colombo. They built a fort in close proximity to the ocean and made it the centre of their administrative and economic activities. The Beira Lake ensured that the fort was surrounded by water on all sides: the sea in the north-west and the lake in the south-east. In the 1570s, two Sinhalese kings even tried, but failed, to recapture the fort by draining the lake ‘infested with crocodiles’ by cutting off its feeding canals. But clearly, the moat held strong against the intended internal threat.

It was the Dutch, armed with their deep canal construction and water management expertise, that did the most amount of work in expanding and systematising Colombo’s waterways. In the heydays of their rule, the Dutch envisioned a continuous waterway link from Kalpitiya in the north all the way down to Bentota in the south. In other words, they wanted to link the Puttalam, Negombo, Colombo, Kalutara, and Galle districts by water.

The Dutch successfully connected Puttalam (Puttalam lagoon) and Colombo (Fort) by extending the Hamilton Canal via the Negombo lagoon to Maha Oya. Today, you can reach the Chilaw Lagoon in Puttalam district from Maha Oya via Gin Oya. However, although historical records speak of a link between the Chilaw and Puttalam lagoons under the Dutch rule, such a link is no longer present. The Dutch also connected Colombo and Kalutara—first by linking the Colombo Fort to Dehiwala and from there connecting Bolgoda Lake to Kalu Ganga via Keppu Ela. They failed, however, to connect Kalutara and Galle, i.e. Kalu Ganga and Bentota River.

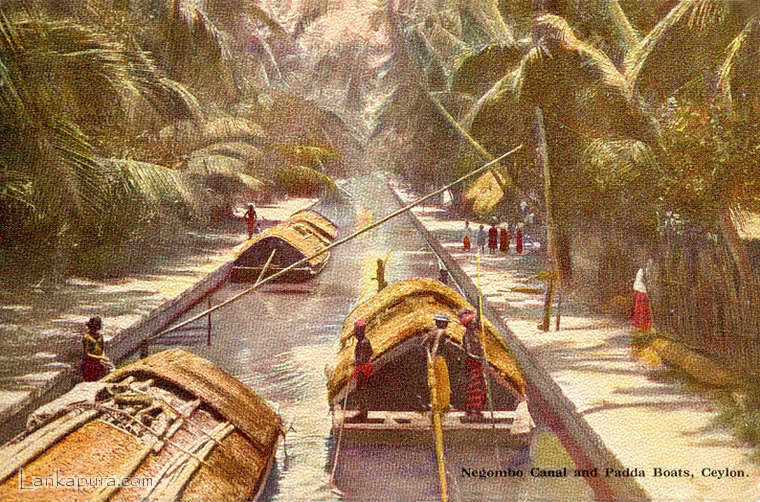

The Dutch also introduced the low-draft ‘padda boats’: a flat-bottomed, punt-shaped barge with thatched cadjan roofing. Labourers either punted or towed them on the towpaths along the canal banks. As author Carl Muller notes in his book ‘Colombo’, that padda boats brought ‘goods such as tea, rubber, copra, graphite, arecanut, and timber to the Port of Colombo’ and took back ‘salt, bricks, tiles, pottery etc. that were needed in the villages.’ Boatmens’ songs that are a part of the Sinhalese music tradition, largely revived only on occasions such as the traditional New Year today, also have their roots in these journeys. According to the author Godwin Witane, the singing helped lighten the boatmen’s burden and drudgery. Some writers also trace the rich expertise in carpentry in Moratuwa to the waterway based economy of the Dutch era: padda boats moved wood logs from the forests in Ratnapura on Kalu Ganga, and then brought them to Bolgoda Lake, and a carpentry industry boomed in the region as a result.

The British, too, in their early days, invested in the canals. The Hamilton Canal is named after the British Government Agent Gavin Hamilton, who is said to have carried out extensive reconstruction in the early 1800s on what was left behind by the Dutch. Government Agent of Western Province, C. P. Layard built the Kirulapone-Wellawatte canal in 1874, ostensibly to prevent flooding. But the canal’s bed was found to be at a higher elevation than the catchment area it was supposed to drain, and thus became known as Layard’s Folly. The British gradually lost interest in inland waterways, and introduced railways, roads, and motored cars to the transportation mix, and as the 1949 Donald Ratnam Transport Commission concluded, the canals fell into considerable neglect during World War II.

A Period Of Neglect

Things did not get better after the British left—barring the occasional grand revival plan. And most of these plans didn’t get past their feasibility assessment. For instance, in 1970, the State Engineering Corporation (SEC) studied the feasibility of cargo freight between Puttalam and Colombo via the 130 km climb-free waterway link, comprising rivers and lagoons interconnected by man-made canals. The plan was to move large quantities of cement, coconut produce, salt, foodstuffs and other cargo between the canal catchment area and Colombo, thereby easing the traffic on the roads. More committees, more studies, and a string of report filings followed. In October 1974, a number of ministries came together and filed an interim report on the project. A year later, the Ministry of Planning and Economic Affairs set up a multi-stakeholder committee to work out the implementation details of the first phase of the project. In 1976 and 1977 this working committee carried out at least three separate studies on the different aspects of implementation—technical cooperation, transport modes, marketing etc. In 1978, a different ministry, the Ministry of Local Government Housing and Construction, appointed another multi-stakeholder committee, and conducted yet another economic feasibility study. The 1981 August edition of Economic Review journal notes that this endless cycle only came to a halt after yet another committee—this time, ironically, headed by two Dutch transport economists —concluded that expanding the canal for transport economic reasons was unjustified.

It took a large-scale disaster in the form of damaging flash floods in June 1992 for the government to finally act. With a USD 110 million loan from the Japanese Overseas Economic Cooperation Fund(OECF), the SLLRDC dredged sections of the waterway system, relocated some of the low-income settlements that had cropped up on canal banks, and demarcated marshlands for flood retention. By 1997, most canals inside of Colombo had been repaired and the SLLRDC had begun sourcing proposals for value addition through public-private partnerships, boat transport, canal tours, sports activities like rowing, and restaurants, both of the floating type and permanent, on canal banks. It is safe to say these partnerships did not materialise.

There have been more recent attempts at value addition as well. In 2010, the Rajapaksa government launched a boat service from Nawala to Wellawatte via the Wellatte Canal. The service began by transporting students to the Open University, for a course offered at the time. The service was dropped for the lack of demand upon the completion of the course. According to Ranoshi Siripala, an ecologist at the SLLRDC, the failure to get the unit economics right and deploying fishing boats retrofitted with seats had contributed to the demise of the service. Just this month, on August 22, 2019, the Ministry of Megapolis and Western Development launched an air-conditioned boat service on the Beira Lake from Colombo Fort to Union Place—a two-kilometre stretch in Colombo’s commercial centre, where the road link experiences heavy congestion during peak hours. The service is offered free of charge for the first month by the Sri Lankan Navy, after which the ticket is expected to cost less than Rs 50. Starting at Lake House, the carrier will stop at Fort, Lotus Tower, and finally, call at Union Place. While it takes approximately 30 minutes to traverse the same stretch by bus, the newly launched service is expected to take only 10 minutes. The Navy plans to operate the passenger boats between 7 AM and 10 AM and 4 PM – 9 PM. If this pilot scheme is successful, plans are afoot to begin a similar service between Battaramulla and Wellawatte via the Wellawatte Canal (an 11 kilometre stretch, cutting across six major roads in central Colombo) and also in the Kelani River (a 35 kilometre stretch connecting Colombo Fort to major peri-urban settlements such as Peliyagoda, Kelaniya, Kaduwela and Malwana). Nearly all of Colombo’s major roads run from north to south enabling strong radial road connectivity around the city. Policymakers believe that canal-based transport could provide a valuable transverse link from west to east and ease the congestion on the roads.

Essential, Not Optional

Attempts at value addition or creation centred on the waterway system must be welcomed. But there are other reasons, far more fundamental, for keeping the system of waterways clean, dredged, and navigable.

Foremost, Colombo sits on low lying land: parts of the city are just above mean sea level (MSL) while others are below MSL. Given this geographic reality, it is easy to appreciate why preserving the marshlands’ boundaries and the canals’ water carrying capacity are important for flood prevention. With impending Climate Crisis these tasks become all the more critical.

Secondly, although the government relocated close to 6,000 families from low-income settlements alongside the canals between 1993-1997, even today a large number of urban poor still live next to polluted waterways. These communities represent some of the most vulnerable sections of the population. A 2015 Kelaniya University study found that the residents living adjacent to the St. Sebastian Canal ‘frequently suffered from skin sepsis, fungal infection, vector borne diseases such as Dengue and Filariasis, waterborne diseases such as diarrhea, hepatitis, and typhoid,’ and called for ‘immediate control measures to overcome the health impacts of water pollution.’

And there is thirdly, the problem of ocean pollution: 80 percent of marine plastic pollution originates from land-based activities and enters the ocean via inland waterways. Sri Lankan divers confirm that where a canal outlets into the ocean in the western coast, there is an incredible excess of plastics. And preventing the outflow of plastics is central to the scheme of combating marine plastic pollution.