.jpg?w=1200)

For Kendrick Fernando (19) and his fellow passengers, the process took more than 14 hours. They landed at the Bandaranaike International Airport (BIA) on March 15, but only arrived at the Vavuniya quarantine centre the next day.

Although they were some of the first there, the camp was at capacity by the end of the next day, holding as many as 200 people, as the government moved swiftly to round up all those returning from countries identified as ‘high-risk’ for the novel coronavirus COVID-19.

The first case of COVID-19 was detected in Sri Lanka on January 27, when a Chinese tourist leaving the country developed symptoms and later tested positive. She was admitted to the National Infectious Diseases Hospital (IDH) and discharged nearly a month later, on February 19.

Proactive action only began early March, after the first local case was detected when a tour guide tested positive. Within 24 hours, schools were closed as a precautionary measure and online visa facilities suspended for a number of countries.

Returning Home

Fernando, who is studying Robotics, Mechatronics and Control Engineering in the United Kingdom (UK) decided to come home as he was not sure how things would pan out in the UK over the next few months.

He also preferred to be with family than alone at this time. Speaking to Roar Media, Fernando said that as soon as the passengers on flight QR 654 disembarked, they were met with airport officials and defence staff, who separated them based on the country they were arriving from.

They were then taken to a small building on the outer edges of the airport complex, where their clothes, hands, shoes, and luggage were sprayed with disinfectant, before they were instructed to wash their hands and screened for COVID-19 symptoms.

“We didn’t know [for sure] if we would be quarantined until we landed,” said Mehak Sangani (22), a student also returning from the UK and currently quarantined in Diyatalawa. “The anxiousness and uncertainty of not knowing was worse than actually going through the process…”

For Sangani, like many of the other students returning, the decision to come back home was precipitated by a general dissatisfaction and unhappiness at the response of the country they were studying in, to the global pandemic.

Universities deciding to close down and a longing for home at a time of great uncertainty were also deciding factors.

“I got slightly emotional when I knew my family was at the airport, and I couldn’t actually go to them,” Seraiah Fernando (19), a first year law student told Roar. “It was an unusual feeling, to be in the same country and not be with them.”

The Process

Strict regulations were imposed on all those arriving, irrespective of nationality. They were made to sign a health declaration form specific to COVID-19 — which included questions about their travel history over the last 14 days, details of any symptoms or illnesses they may have, and details on where they planned to stay in Sri Lanka.

The returnees then spent some hours at the airport — ranging from six to 12 — waiting for more arrivals so that they could be sent together to the assigned quarantine centres, which were often, quite a distance away.

“I found some friends and other students I know, so it wasn’t as bad for me. But also travelling on my flight were some elderly passengers and a single mother with two children,” said Tharaka* (20) a student returning from the UK, currently at the Diyatalawa quarantine centre.

All passengers were taken by bus to the quarantine centres with a police escort. At the centres, they were subject once more to a process of disinfection before entering, and then segregated based on gender.

The Facilities

Food, clean rooms and bathrooms, a variety of amenities in addition to wifi are provided across the board. Towels, a mug, tea bags, milk powder and toiletries were also some of the things made available to them.

They were also given medical masks and a list of important telephone numbers to call in case of an emergency. These included the telephone numbers of brigadiers overseeing the camp, administrative officers and medical professionals.

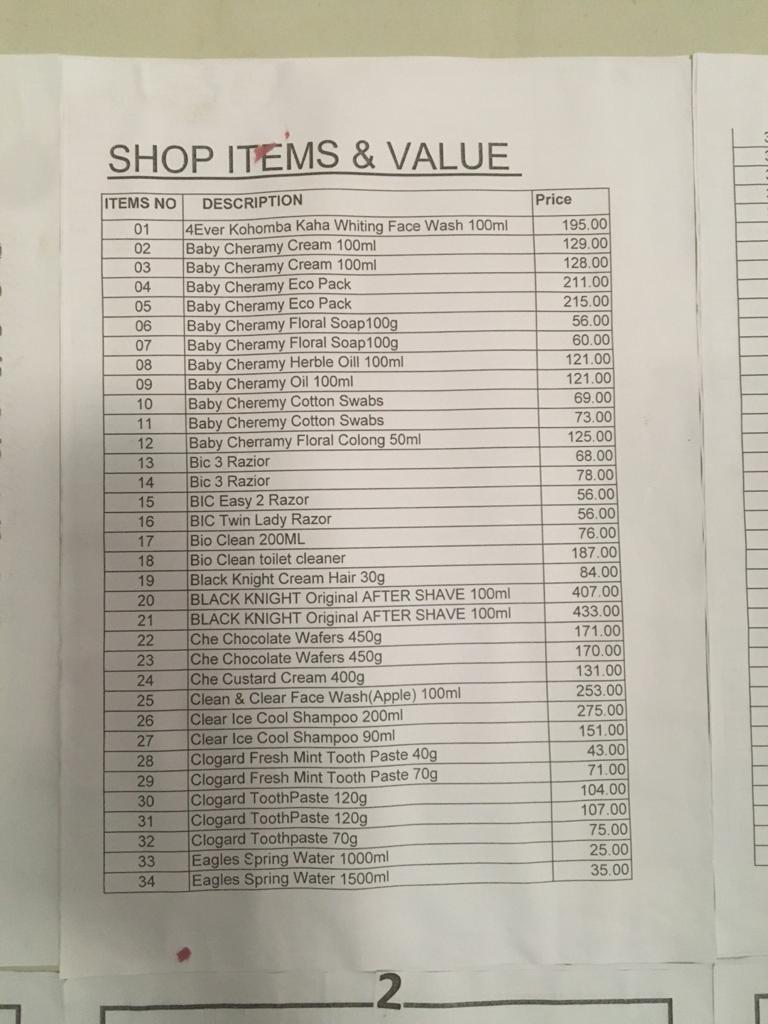

“We were also given an extensive list with [items and their corresponding prices], which we could request and pay for if we needed anything extra,” Fernando said of his experience at the Vavuniya quarantine centre.

The returnees were briefed on the virus and on guidelines and measures that had been implemented by the government, to prevent community transmission.

“Even as a medical student, I didn’t know [that much] in detail,” Dinul Hettiarachchi (20), a returning student who has been providing updates on his quarantine experience on social media, told Roar Media.

Lockdown

Those in quarantine are not allowed to leave their assigned block or bungalow. During meals, packages of food are deposited by the staff at a preselected place, so that those in quarantine can distribute among themselves, reducing interaction between themselves and those manning the centres.

Those in quarantine have also been advised to reduce interaction, to maintain some distance between each other and to wear masks when stepping to outside areas within the allowed confines.

To pass the time, they complete work, assignments, play games, read, watch movies and catch up on sleep.

“This [inability to communicate] can be frustrating, but we understand the situation,” Tharaka said. “I think Sri Lanka is quite ahead, compared to the rest of the world. We are doing everything we can to flatten the curve.”

Medical officers also keep a close eye on the returnees. In some centres, doctors and nurses — dressed in protective gear — visit those in quarantine, while at other centres, daily check-ins are conducted over the phone.

A key element to the success of the programme is the manner in which the returnees were treated by the tri-forces. “We have everything we need and nothing to complain about,” Fernando told Roar. “We are not too worried. We have placed our trust in the officials at the camp.”

“I had a lot of friends who had to leave the UK to come back to their home country, but no one I knew had to be placed in quarantine,” Sangani said. “I was particularly proud to be a Sri Lankan at this point, where proactive measures are being taken.”

All interviews were carried out over the phone or on video-call. Special thanks to the interviewees.

* — name has been changed to protect identity.