It takes roughly 10 minutes to wear the entire ensemble; the complete outfit of any doctor or nurse tending to a patient who has contracted the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). It is cumbersome and confining. The outfit is also the primary protection for the health care workers who are at immediate risk of being infected themselves in this pandemic.

Dr Priyankara Jayawardana, a consultant physician, tested positive for COVID-19 after coming into contact with another patient on 20 March. He was treated at the National Infectious Diseases Hospital (IDH) for 11 days and then released. He wrote on his social media: “I came home yesterday evening. Two consecutive COVID PCR tests for the virus were negative.”

For every health care worker that contracts the disease, there is one less doctor or nurse available to help a patient. The only precaution is to gear up. However, with the unprecedented spread of the disease, the world is facing a dire shortage of protective equipment.

What Is PPE?

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for health workers is at an all-time low in the world. In the United States, doctors and nurses facing the shortage are forced to wear bandanas and scarves for masks, trash bags for gowns, and reuse medical equipment — heightening the risk of COVID-19 infection and possible death.

The severity of the crisis is also felt in Sri Lanka too.

Video: https://twitter.com/WHOSriLanka/status/1243929314015375360?s=20

A health worker donning the cumbersome PPE outfit. Video Credits: WHO Sri Lanka.

“At present, our daily consumption of PPE ranges from 2,000 to 2,500 kits at all hospitals and quarantine centres, treating or testing for COVID-19,” Dr Kapila Wickramanayake, Director of Medical Supplies at the Ministry of Health, told Roar Media.

Since the beginning of the outbreak to present, 30 hospitals have been compartmentalised to either test for suspected COVID-19 cases or treat those cases who were identified with the disease. One of the primary treatment centres is the IDH in Mulleriyawa, at which a single health care worker uses 10 to 15 PPE kits each day.

“This is an abnormal situation,” Dr Wickramanayake explained. “There was a huge increase in the demand following the outbreak, which has led to several minor issues — globally as well as locally. We are definitely feeling the impact of this. However, I believe we are managing and maintaining what stocks we have.”

Missing Masks

One of the challenges that gained prominence during the initial stages of the outbreak was the shortage of medical masks in the market.

The demand for medical and surgical masks saw an unprecedented increase following the discovery of the first COVID-19 patient in the country back in January. Even though face masks were not mandatory at that time, many were seen panic buying and hoarding face masks in the following weeks.

While the stocks managed to support the increased demand for a few weeks, by February and March, the mask stockpiles had more or less depleted.

Proof of this arrived when Professor Neelika Malavige of the Dengue Research Centre of the Sri Jayewardenepura University and her team of virologists, who are testing biosamples for COVID-19 diagnosis, reported a shortage of N95 surgical masks.

“Since we handle biosamples from patients, N95 masks have become essential for us,” she said. “However, since people are misusing facemasks and surgical masks, there’s a shortage of it in the market. We would like to request everyone to use alternatives so that essential services such as the health sector can utilise it.”

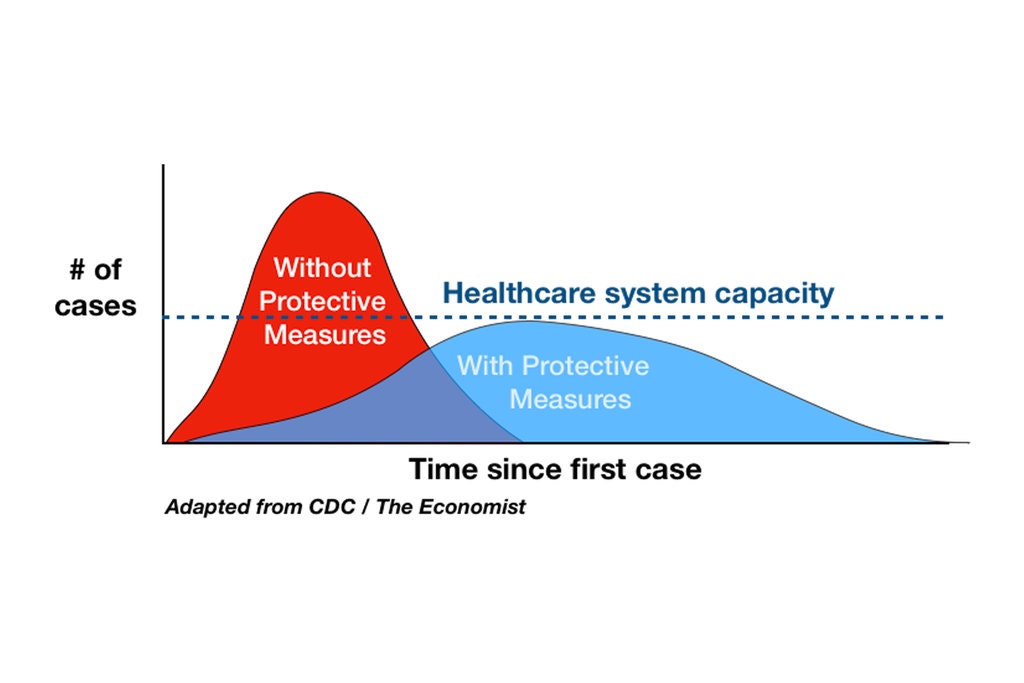

There are two significant ways in which the curve can be flattened; one is to practice social distancing. This would reduce the number of those infected and the spread of the disease, and would not overburden the health workers. The second solution is to develop more capacity so that frontline workers can handle more cases at once.

If capacity falls — if doctors and nurses get sick because of a lack of protective equipment, or refuse to work without conditions that can ensure their safety — even the flattest curve would be hard for a system to handle.

Locally Manufactured

As for medical supplies, Dr Wickramanayake of the MOH said, the purchase of PPE and other medical equipment is still underway, despite the various global restrictions on imports. “Regional institutions and local manufacturers have been of great help. There have been so many donations. Even megascale industries have become a part of this and are helping with manufacturing.”

The local manufacturing of PPE began with Dr Udaya de Silva of the Anuradhapura Hospital and his team designing a DIY-style PPE kit, inspired by garbage bags that collect waste, polythene sealer, aluminum foil with cloth iron and Teflon sheets with soldering iron.

After the design was put forward, large-scale production of the kits was undertaken by Sri Lanka Air Force and the Sri Lanka Army. Similarly, the designs were shared with private sector companies such as Brandix, Hirdaramani, and MAS Holdings and others in the apparel sector, which has begun the PPE production.

Many leading companies of the industry have also discovered the prospects of PPE and face masks manufacturing for export purposes in the current economy; incentivised by the Exports Development Board and the Sri Lanka Foreign Affairs Ministry.

Were We Prepared?

According to Coordinator of the Disaster Preparedness and Response Division of the Health Ministry, Dr Hemantha Herath, Sri Lanka began preparing for pandemics and other unexpected emergencies back in 2018.

“With the increase in threats like the Ebola outbreak in 2018, we had our first emergency response programme. Following this, there were several other programmes that were held regularly. Then the Easter Sunday attack happened in April (2019). After that, the need for better response became obvious,” he said.

In order to successfully address the COVID-19 outbreak, the National Influenza Preparedness and Response Plan was utilised by the Health Ministry to successfully address the crisis. “What we had was a preparedness plan and a very generic action plan. Since COVID-19 is also a respiratory disease, like SARS, MERS, Avian flu, and H1N1, we made use of the influenza response plan. We had to modify it later on to suit the specific requirements of the disease,” he said

According to Dr Herath, these plans and strategies helped prepare the country’s health sector to a certain extent.

“We did not have a crisis in the beginning. We had enough stocks of PPE and other equipment prepared beforehand, as part of the work plan of this division. Over 2,000 PPE kits were distributed last year to hospitals such as the IDH, the armed forces, and other organisations which were likely to be first responders. Because of that, when the COVID-19 crisis struck for the first time, we did not have to face any kind of major shortage in respect of protective equipment,” he said.

With the armed forces set to produce approximately 1,000 kits per day, Dr Herath is confident the country will face the shortage head-on. “Yes, everything was done for the first time and there were many setbacks. Looking back, we can spot the mistakes, the delays, and the panicked reactions. Yet, there was no major crisis because we were ready,” he affirmed.